UCSB Researchers Studying El Niño Sea Level Rise

Data Will Be Used for Future Coastal Planning

Since the arrival of El Niño in November, sea levels have risen 20 cm to become a surrogate for the next 250 years of climate change, giving scientists the prime opportunity to study future erosion of the Santa Barbara coastline.

In the 1960s, developers of beachfront homes set foundations several yards away from cliff edges in the belief that the residences would last for another century. The ocean has since caught up, and researchers at UCSB suggest coastal planners use their findings to design solutions for human structures and natural ecosystems. The team is currently analyzing erosion at nine research sites, extending from Coal Oil Point Reserve to Shoreline Park, with the assistance of a California Sea Grant by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

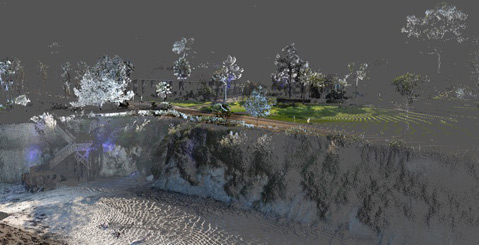

Researchers began the project in October, using an eggcrate-sized light detecting and ranging (LiDAR) scanner to create high resolution, 3-D images of each site. While spinning 360 degrees atop a tripod, the LiDAR shoots invisible infrared lasers into the landscape and makes about 14 million data points every 20 minutes. “There have been other studies that have measured erosion and other processes, but not as high resolution as we’re able to get now,” said Paul Alessio, UCSB graduate student under Ed Keller, professor of earth science.

The team has been revisiting each site after significant storms, every two to three weeks, to create a time-series of sea-level rise in the El Niño season. Because the regular sea level is expected to rise 20 cm over the next 25-100 years, the group is using El Niño conditions as a predictor of future erosion rates. The group will also use NOAA buoys to track swell direction, large “king tides,” periodic wave cycles, and several other factors in their analysis of cliff erosion. (Image Credit: Terrestrial LiDAR scan)

Geology

The near-vertical cliffs of Isla Vista and the bluffs of More Mesa are part of the Monterey and Sisquoc rock formations, mainly comprised of shale rock. Packed above the million-year-old Sisquoc is much younger sand, which is susceptible to erosion. According to Alex Simms, UCSB professor of earth science, the positioning of coastal rockforms determines their susceptibility to erosion. Big storms in the relatively tucked-in coasts of Isla Vista can cause erosion of 15-17 cm per year, while an area with jutting-out rocks, such as Hope Ranch, can be susceptible to erosion of nearly 37 cm per year.

Attempting to curb this natural process, however, may contribute to even faster deterioration. A common method of protecting beaches from erosion is the placement of rock revetments, large boulders which protect the base of the sea cliff. Although these boulders reduce erosion in oceanside areas, they ultimately interrupt the natural equilibrium of sand, which flows from the north to the south. Harsh winter waves deplete the sand, while summer waves carry sand ashore. When confronted with obstructing boulders, waves hit the sand with greater impact and strip material away from the coast, creating narrower, steeper beaches. “Whether we like it or not, the coastlines have been receding for 20,000 years, in some places meters per years,” Simms said. “We obviously like our ocean views, so we like to build houses, but we often forget that the coastline is a very ephemeral feature. It’s moving always.”

Ecology

Santa Barbara’s coastline also suffers from the presence of weedy exotic plants. The ice plant, also known as the Hottentot-fig, is one of “worst” invaders of native ecology, Alessio said. The nonnative ground cover has shallow roots and is comprised of 90% water, weighing down the cliffs and doing little to keep natural rocks together. Native plants develop long roots over a number of years and can impede the natural crumbling of the sea cliffs. Alessio said the nonnative plants contribute to “larger failures” within coastal ecosystems, rather than mitigate the effects of erosion and climate change. Several environmental protection groups have begun organizing cliff restoration projects, replacing ice plant and its invasive brethren with native groundcovers such as morning glory and beach strawberry.

Coastal Planning

After beginning the study in October, the researchers have had optimal conditions for data collection, running LiDAR in the test sites during the stormy season of February. Although El Niño is predicted to end toward March and April, sea levels can be raised for up to six months afterward, and the study will continue for two years to map a timeline of sea-level conditions. Alessio said, as a general trend, sea levels in the Santa Barbara coast have been slowly rising for 100 years.

Now, the job of the researchers is to collect data and understand how the rate of sea level-rise, which has nearly doubled in the last 50 years to become about 1.25 mm a year, will continue its curve upward by the end of the 21st century. In the following years, the team will be working with several organizations, including the California Coastal Commission (CCC), to develop user-friendly maps and tools for coastal planners. Governmental organizations will then be able to use this research as they decide whether to prioritize coastal ecosystems, man-made developments, or a mixture of the two.