Colson Whitehead Tackles Slavery

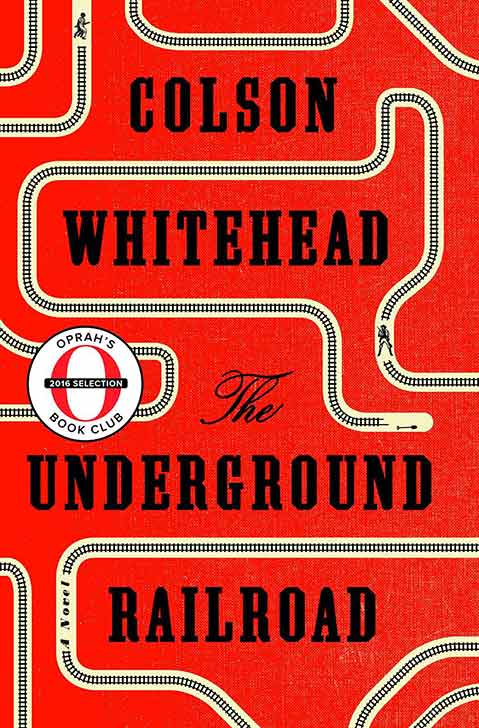

Author Presents Alternate History in ‘The Underground Railroad’

The first 50 pages of Colson Whitehead’s new novel, The Underground Railroad, contain the most unremittingly grim portrayal of slavery since Toni Morrison’s Beloved — more so, perhaps, as Whitehead avoids Morrison’s high-flown (and occasionally distracting) literary language. However, while Whitehead’s readers may be wondering if they can bear the next inequity visited upon the novel’s indomitable protagonist, Cora, they may also be thinking: How can American authors write about any subject other than slavery? After all, willful forgetting of slavery’s legacy allows for such dizzyingly ahistorical statements as Donald Trump’s comment in September that “our African-American communities are absolutely in the worst shape that they’ve ever been in before. Ever, ever, ever.”

Not surprisingly, Whitehead chooses not to sustain the agonies of the opening pages — the novel would probably have been impossible to read if he had. Instead, the book becomes an alternate history, with a touch of magical realism. The actual 19th-century Underground Railroad is transformed into a literal network of tracks running beneath America in a “gigantic tunnel … twenty feet tall, walls lined with dark and light-colored stones in an alternating pattern.”

In the imagined world of the novel, each Southern state is its own microcosm: South Carolina is an apparent beacon of relative enlightenment, although Cora soon realizes something sinister lurks in its placid paternalism; there is nothing subtle about the horrors of North Carolina, which manages to outdo the violence of Cora’s home state of Georgia; and Tennessee is a virtual wasteland. Not every white Southerner in The Underground Railroad is evil, but “the peculiar institution” itself is so malignant that it infects everyone and everything it touches.

While some readers might fault Whitehead for using fantasy to dodge the full monstrosity of slavery, The Underground Railroad’s unlikely premise makes it all the more enthralling. As a charismatic biracial abolitionist says toward the end of the novel, “Sometimes a useful delusion is better than a useless truth. Nothing’s going to grow in this mean cold, but we can still have flowers.”