Homeless Issues Then as Now

Cottage Hospital Celebrates 125 Years of Healing

Mary Ashley is another Santa Barbara pioneer too interesting for history to much remember. But without Ashley, Cottage Hospital would not exist today and this Thursday’s grand birthday bash to celebrate its 125 continuous years in service would have never happened.

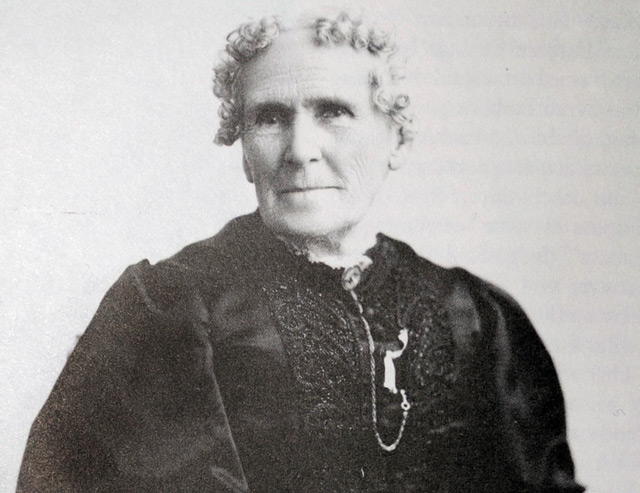

Photos of Ashley taken in her sixties suggest a stereotypical late-19th-century do-gooder and civic civilizer: a stoutly built, square-jawed woman with thin lips, steady gaze, and redoubtably kind eyes. She was an ardent feminist long before the term was coined, states Elizabeth Gilbertson, a freelance historian — a suffragette who championed women’s right to vote as early as the 1870s. If ignorant and inebriated men were allowed to vote, Ashley argued, women should have the same right. Like many protofeminists, Ashley was an ardent member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She was also a strong financial supporter of the Spiritualist church, then settling in Summerland.

Ashley’s most lasting impact, however, would be the creation of Cottage Hospital along with 40 other women who came together in 1888. The founding mothers emerged from the ranks of upper-crust Yankees moving west, educated, older, and mostly Protestant and Unitarian. But it was Ashley who made their collective dreams come to fruition, serving 10 years as president of Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital Society. And it was Ashley who came up with the name. Initially, Cottage Hospital was to be made up of small adjoining cottages, the theory being that they allowed for better air circulation. High construction costs proved prohibitive, so the first iteration of Cottage was a big three-story Victorian box instead. Still, the name stuck. “It has such a cozy sound,” Ashley once explained.

When Cottage opened its doors for patients on December 8, 1891, 5,800 people showed up to celebrate. That was roughly two-thirds of the city’s population. People brought kegs of cider, live turkeys, decorative plants, and foods of all sorts. In its first year, Santa Barbara’s 25-bed hospital cost $2,100 to operate. Revenues exceeded costs by 51 cents, but only because the chief administrator, Dr. Jane Spaulding, took only half her salary. Since then, Cottage has undergone multiple steel-and-concrete transmogrifications, and it is now in the final lap of an expansive and expensive seismic retrofit and remodel. Today, the hospital boasts a state-of-the-art neonatal intensive care unit, an emergency transport helipad, a suite of emergency rooms that experience 75,000 visits a year, 513 licensed beds, and expenses of roughly $661 million.

One of Ashley’s chief motivations in getting Cottage off the ground was the provision of health care to “the homeless.” That term meant something decidedly different 125 years ago and was used to describe teachers, clerks, and tourists. Despite such obvious differences, however, Cottage Health — as it is now known — remains no stranger to the urgent demand for today’s homeless services. Santa Barbara County’s homeless population — hovering at about 1,450 — have always been sicker and frailer than the population at large. But according to Cottage ER doctor Jason Prystowsky, they’re getting sicker and older still. This means multiple visits to emergency rooms, placing a heavier burden on resources already keenly stretched.

To help address this need, Cottage Health assigned Laurie Biscaro, a nurse with Cottage since 2002, to manage the hospital’s case management department. In dealing with the homeless, she and social worker Sal Robledo convene meetings every Monday morning to discuss the transitional needs of homeless patients about to be discharged from Cottage. They also track the progress — and challenges — confronting those already released. Their aim is to get patients stabilized. To this end, Biscaro and Robledo collaborate regularly with a small blizzard of social service workers, representing multiple nonprofit and government agencies. “Every last homeless person we treat is someone’s baby,” Biscaro declared. “And they didn’t grow up thinking they’d be homeless.”

Patients without homes can be notoriously difficult to treat. Some don’t follow doctors’ advice; many lose their prescription medications, have them stolen, or lose them to law enforcement confiscation. Many also suffer from mental illness or substance-abuse problems. Traditionally, few have been insured, though with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, Medi-Cal eligibility requirements were relaxed. Cottage, Biscaro said, has signed up as many homeless patients as possible.

Even so, many remain uninsured and are definitely not in the habit of seeing primary care physicians. To the extent homeless persons seek medical treatment, it’s disproportionately via the nearest emergency room. While Cottage Health doesn’t track the total number of ER visits by homeless individuals a year, Robledo said the top 20 users alone accounted for 650 visits. That translates to nearly three visits a month. In the jaded lingo of homeless health care, these patients are known as “Frequent Flyers” or “Million-Dollar Murrays.” But in Biscaro’s parlance, they are known more warmly as “HUGS.” That stands for “Higher Utilizer Group Services” and refers to the wide array of “wrap-around” care necessary to keep such patients reasonably healthy.

For many years, Cottage Health has reserved up to 350 beds a month at Santa Barbara’s downtown homeless shelter — PATH Casa Esperanza — so that homeless patients discharged from Cottage and needing medical respite will have some intermediate shelter space. Cottage has paid PATH about $262,000 annually for those beds and determines how much time patients need. County Public Health provides a nurse, some access to mental-health treatment, and, for three days a week, a satellite health clinic. Anecdotally, such beds are available to individual patients for three to five nights. For homeless patients too sick to walk or feed themselves, Cottage struggles to find placement in skilled nursing facilities.

Homeless advocates are quick to praise the ingenuity, creativity, and generosity of Cottage’s ER doctors. Cottage Health granted $70,000 this year to Doctors Without Walls’ Wrap Around Care Program, and it helps fund Central Coast Collaborative (C3H), a nonprofit collaborative specializing in homelessness. But increasingly, public health administrators, health-care professionals, and homeless advocates are concluding that the current constellation of services available to address the transitional needs of discharged homeless patients — known as respite or recuperative care — is simply not adequate.

In its most recent report, Santa Barbara County’s Homeless Death Review Team concluded that there remains an “urgent need for medical respite services to care for homeless patients discharged from the hospital who have skilled nursing needs. The shelters are inappropriately used as skilled nursing facilities because of a lack of alternatives, and these patients have poor outcomes and high rates of re-hospitalization.” The county’s Public Health Department is now collaborating with C3H to create a long-term housing project in North County, though the project remains very much on the drawing boards.

While hardly unique to Santa Barbara, this service gap is achieving critical mass as a public health issue. This May, Hope of the Valley shelter in the San Fernando Valley spent $4.3 million to build a 30-bed recuperative care shelter targeting medically discharged HUGS. To date, it’s running at 80 percent capacity and offers an intensive array of medical, mental-health, and detox services currently unseen in Santa Barbara. Operating costs are absorbed by four of the largest 17 hospitals operating nearby to the tune of $250 per bed per night. It’s too soon to determine what reduction the new center is having on nearby emergency rooms, but shelter CEO Ken Craft said the math is pretty simple. “If they’re here, they’re not there,” he said.

National studies on recuperative treatment indicate the average length of stay is 32 days. Craft noted that the Affordable Care Act has increased the regulatory pressure on hospital administrators to keep a lid on readmission rates. Another recent study revealed that readmission rates for homeless patients in Boston was dramatically lower for those discharged to recuperative care. A 2010 report by Santa Barbara’s Homeless Death Review Team concluded that Santa Barbara’s “most vulnerable” homeless consumed $3 million worth of hospital treatment.

“There’s no such thing as a silver bullet when dealing with the homeless,” said Jason Prystowsky, the Cottage ER doc active with Doctors Without Walls. “But if there were, one would be intermediate respite care and the other would be inpatient and outpatient mental-health treatment.”

The need, said Prystowsky, is both urgent and obvious. But care providers throughout the community are overwhelmed by their immediate challenges, not to mention their financial survival, and no one — outside of Chuck Flacks, executive director of C3H — is leading the charge to make expanded recuperative care happen. It’s very expensive, Prystowsky stated. More than that, the issues of management and oversight are complex and demanding. “We’re all so overwhelmed right now,” he said. “It’s hard to be pro-active and take on so large a problem.”

What role Cottage Health may play remains to be seen. For the past year, it has been conducting an aggressive needs assessment as part of a new population health initiative. By combining the results of a high-profile listening tour and polls with health-care data capable of differentiating the unique challenges confronted by homeless people at Pershing Park as opposed to Ortega Park, Cottage administrators are “setting the groundwork for community partnerships and collaborative review of new initiatives aimed at specific health programs,” said hospital spokesperson Maria Zate.

In the meantime, Biscaro stated, “We need more beds.” And, she added, the county needs what’s known in the social service lingo as a “harm reduction” program. Translated, that means a large place where chronically ill homeless people can live and receive focused treatment, even as they continue to drink and abuse drugs. To expect sobriety from such patients is not realistic; by getting them under one roof, Biscaro said, case managers can target their treatment more efficiently while reducing expensive complications caused by exposure to the elements. Such a facility, she said, exists in Seattle, but it’s located in a large converted warehouse in an industrial part of town.