‘A Living Hell’

Hiroshima: August 6, 1945

Born in 1927 in Los Angeles, I lived with my mother and father for my first year, then my mother took me to her homeland and to her village of Nukushina in Hiroshima Prefecture. When I was in the 4th grade, my father joined us in Japan. I grew up in a family of five boys and two girls.

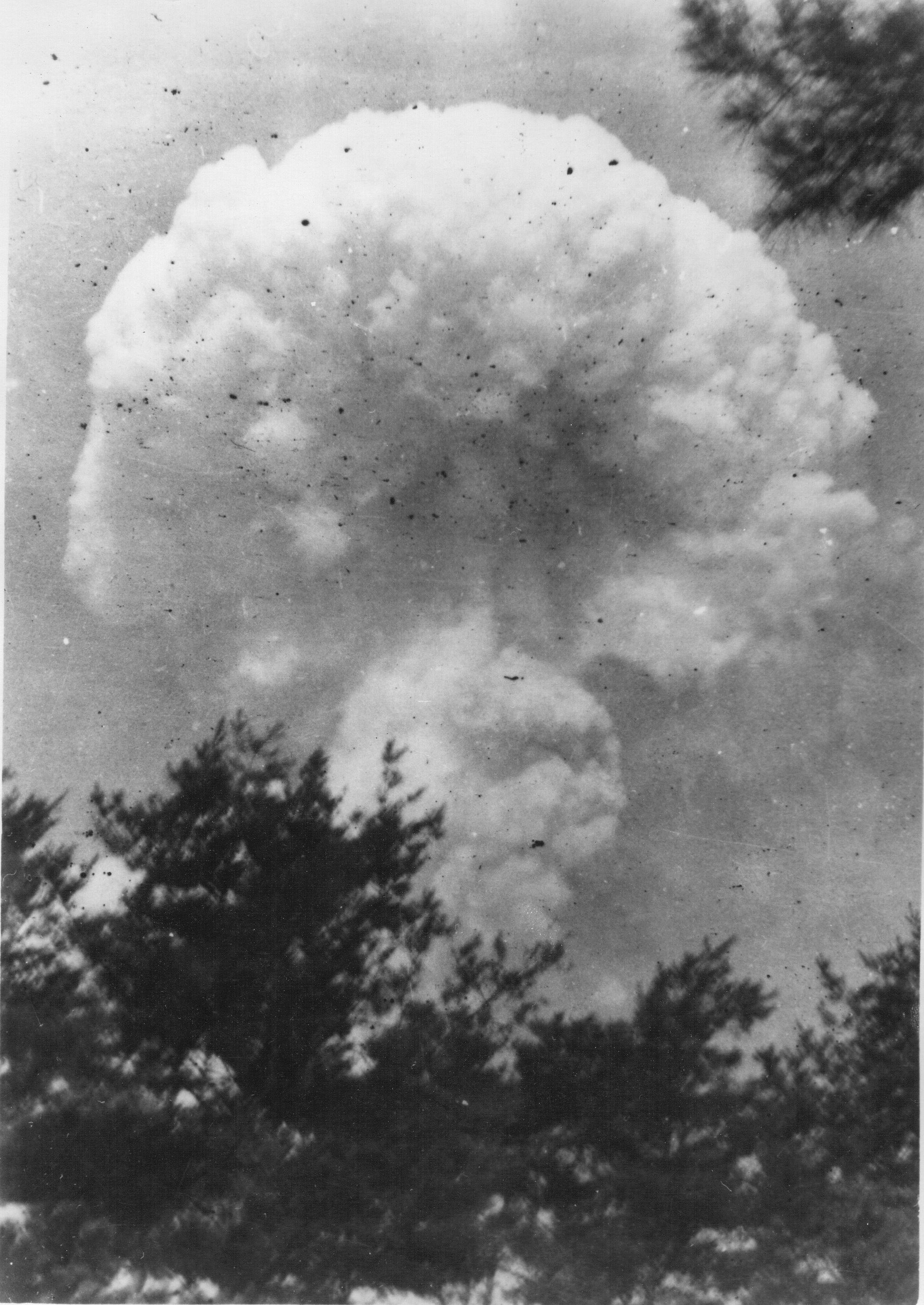

On August 6, 1945, I was at school, attending an engineering class. The lecture on “Strength of Materials” had just begun at 8 a.m. At 8:15 there was a big flash of light and the huge sound of an explosion that shook the building. My friend Ko Hata sat beside me, and we both dropped to the floor.

My first reaction was that the B-29 I had seen earlier had come back and dropped a bomb very close to us. I worried that another would be dropped soon, so we stayed down. Unfortunately, many classmates had stood up and were hit by flying broken glass. Nobody was saying anything. The classroom was totally silent. It took a long time to learn that the first atomic bomb of World War II had been dropped on our city. Our classroom was situated about 2.5 miles from ground zero.

My friend sensed his parents might not be alive because their house was near the center of the city. So I told Ko to come to my place. We picked up my old bicycle at the shop, and we started walking toward home.

As we reached the busier part of the city, streams of people came toward us, suffering from burns and cuts. They were saying, “Give me water, give me water.” I can never forget the sad sight of the skin on their faces hanging down, their badly burned hands raised above their chests as they walked down the street, crying. It was a living hell.

One lady was suffering so much she could not walk very well, but she wanted to get to the grammar school where a first aid station was set up. We put her on the bicycle and took her to the school. An air raid warning sounded, and most people on the street took cover. But we kept walking.

When we arrived home, my mother was so happy to see us safe. The shock wave from the A-bomb had raised the ceiling of our house about three feet, but my parents were safe. Unfortunately, Ko’s sense about his parents was true, and he lost both of them.

After the A-bomb fell on Hiroshima and then Nagasaki, Russia invaded Manchuria. These one, two, three punches really finished Japan. At noon on August 15, 1945, the emperor announced on national radio that the war had ended.

I continued my studies, on my brothers’ advice, and sailed to the U.S. aboard the General W.H. Gordon in 1949. (One brother was in the U.S. Army Air Corps in China during the war, two were imprisoned at Tule Lake, and a fourth was in the Japanese Army, also in China.) Now a kibei, or a Japanese American who had studied in Japan but returned to the U.S., I was given the nickname “Kenny” by my sister-in-law and began to learn English. Eventually I got a diploma from UCLA, began working as a government meteorologist, and found myself back in Japan in 1983 with the U.S. military.

The Japanese government has monitored the health of A-bomb survivors in Japan and other countries. While I was there, I was able to get free and complete physical exams. I was issued an “A-Bomb Survivor Health ID Handbook” in 1994 by the mayor of Hiroshima, and when I returned to California, I began to meet medical doctors in Los Angeles for physical checkups every other year.

My hope is that many people would have the chance to visit and see present-day Hiroshima. Its history museum has an exhibit of the bomb’s effects on the city and its people. I think all people come away from it wishing: No More Hiroshima in the Future.

Yoshito Yamamura died suddenly a year ago of an acute illness unrelated to his teenage wartime experience.