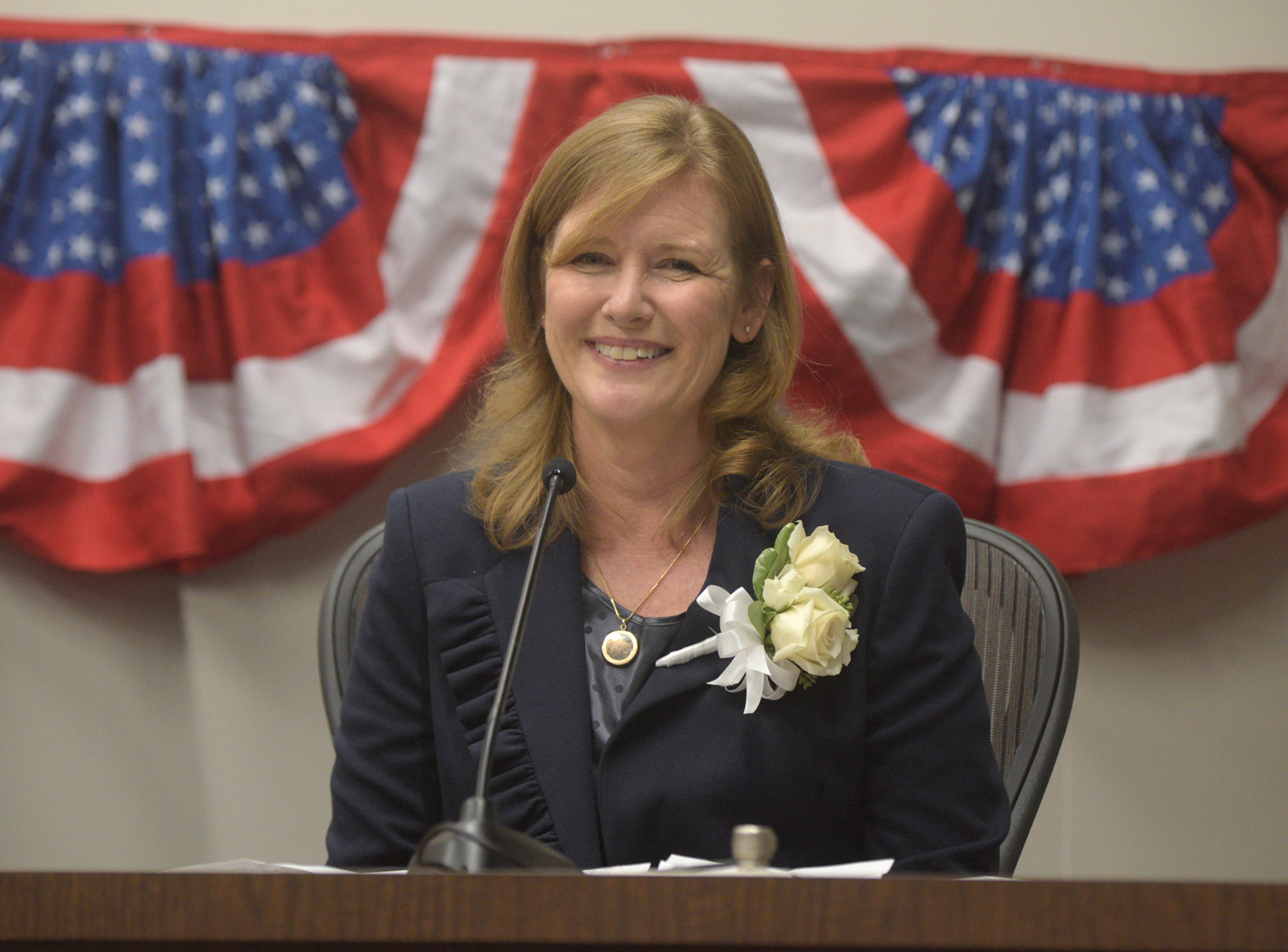

Murillo Sworn In as Santa Barbara Mayor

New Council Starts Sweet Then Veers Sour

There was a palpable abundance of celebratory goodwill expressed at the start of this week’s City Council meeting. Cathy Murillo, the onetime newspaper reporter turned progressive councilmember, was sworn in as the city’s 50th mayor and the first Latina ever to hold that post. “I’m standing ready to lead Santa Barbara into an ever-brighter future,” Murillo declared.

Kind words were lavished upon Murillo’s predecessor, Helene Schneider, as she passed the gavel and stepped down off the dais after 14 years of service, along with councilmembers Frank Hotchkiss and Bendy White. “You’ll always be the mayor of Santa Barbara,” Murillo said to Schneider. Both White and Hotchkiss were termed out of office after running against Murillo for mayor this past November and coming up short. Murillo asked Hotchkiss — with whom she frequently sparred — to inscribe something personal in a copy of his novel, a steamy romance, that she had bought at Chaucer’s.

Kind words were heaped in turn on Murillo, as well as newly elected councilmembers Eric Friedman and Kristen Sneddon, who replace Hotchkiss and White. “You’ll be a great mayor,” Hotchkiss said to Murillo as she pulled out his book. Incumbent Councilmember Gregg Hart came in for some laudatory talk, too, getting sworn in after winning his fourth term on council.

But after all the grins, the swearing-ins, and about 30 minutes set aside for punch and cookies, the mood shifted. Old political fault lines reasserted themselves as the new council struggled to answer the thorny question of how to fill the council vacancy created when Murillo was elected mayor. Without a successor, there will be only six councilmembers and no way to resolve a three-to-three deadlock, should one arise. Worse yet, the 3rd District, which Murillo had represented — the city’s largest majority-minority district — would be without representation.

City Attorney Ariel Calonne has insisted the City Charter requires the council appoint her successor within 30 days. A special election in April, he argued, would cost City Hall $300,000. But former judge Frank Ochoa has ever-so-gently threatened to sue if the council doesn’t hold a special election to fill that spot. Ochoa, with a voice like wet rocks, has been retained by remnants of the same committee that successfully sued to force City Hall to switch to district elections three years ago.

The debate was complicated, technical, and procedurally confusing. It was also intensely political and at times pissy. Several weeks ago, the council voted to fill Murillo’s void by appointment. District election advocates have since rallied, complaining that anyone appointed to the post would enjoy the undue advantage conferred by incumbency. “Democracy demands a special election,” declared district supporter Lanny Ebenstein. “Correct me if I’m wrong, but I was under the belief this country was based on democracy,” said Victor Reyes, wearing a black hat with an American flag and black T-shirt with the words “I only look illegal” printed in bold white letters.

They were hoping the council might revisit the issue sometime later this January before an appointment could be made January 30. But before public comment had concluded — there were still three speakers on deck — Council member Jason Dominguez jumped in to make a motion to delay discussion of the issue to a date well beyond January 30. Dominguez is no friend of special elections nor a supporter of Murillo; procedurally, it was a bold if premature move. Murillo objected: “There are three more speakers. Can you hold on?” Dominguez would not budge. “No, I’d rather make it now,” he insisted.

Ultimately both sides would walk away getting what they wanted. Dominguez would get a council discussion of what legal changes to the city’s charter would be needed to allow special elections should council vacancies come up in the future. And district election supporters got a promise at least to discuss a special election two weeks hence. At times, however, it was anything but clear how many motions were on the floor, which one was up for a vote, and which council members were trying to second which motion.

The mayor’s job is to run council meetings, and doing so isn’t nearly as easy as Murillo’s predecessor, Schneider, routinely made it seem. Before Schneider stepped down Tuesday, she was praised for her ability to “herd cats” and to contain council debates within the confines of civil discourse. For Murillo, this is a new and unaccustomed role. The underlying legal issues of this debate, however opaque they seem, could be both immediate and pressing.

Councilmember Gregg Hart is expected to announce shortly his intentions to run for 2nd District county supervisor in this June’s election for the seat about to be vacated by Supervisor Janet Wolf. Should Hart win that contest, this would create another council vacancy and give rise to yet another succession debate over appointments and special elections.

Regardless, the new council will be a very different creature than the one it’s been. With the departure of Schneider, White, and Hotchkiss — the first two being moderate liberals, the latter being a staunch but congenial conservative — the council loses 57 years of institutional memory.

Schneider announced she’d be taking a new federal position coordinating homeless services and another as a liaison with Cal State Channel Islands. She also hosted a benefit fundraiser for the Community Arts Workshop — raising $50,000 — where she belted convincing renditions of Led Zeppelin’s “Ramble On” and Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally.” At the council meeting Tuesday, Schneider took pains to thank everyone — including her mother. Being mayor of Santa Barbara, she said, “is the opportunity of a lifetime.”

Councilmember Frank Hotchkiss was praised for asking great questions and getting “to the heart” of issues quicker than anyone. He was customarily brief in his farewell remarks, acknowledging that his views often were at odds with those of his colleagues. “If you listened to me,” he said, “I know it wasn’t easy.”

It was Council member White, however, who turned his swan song into an aria. White started off as a water commissioner in 1982 and has served in City Hall in various capacities since. A stubborn moderate who took pride in crafting compromises, White highlighted the 10 years he spent trying to get the city’s new general plan approved. “It’s like our bible,” he said. “It’s full of wise things to say and a whole lot of apparent contradictions.” Those contradictions, however, reflect dynamic tensions between the city’s neighborhood preservationists and its social justice advocates who want increased housing densities. These tensions, he warned, will never be tamed or resolved. That needs to be respected and understood, he said. “It’s not, ‘Our side won.'”