Santa Barbara’s Fiesta Horse Parade

One of the Largest Equestrian Parades in the United States

Santa Barbara’s longest reigning spirit of Fiesta has never twirled a flamenco skirt or fluttered a Spanish fan.

It is the horse, with its head held high, its coat gleaming under the August sun, that has always captured the deeper meaning of the Old Spanish Days celebration—an ode to the Californio culture where horses were loved second only to family. As one historian of Santa Barbara’s Fiesta explained it, Old Spanish Days was never meant to be an exacting reproduction of that time between the Chumash civilization and the arrival of the Yankees, but instead “an attempt to capture the essential spirit of the time”—the time when California was controlled by Spain and then Mexico, when Spanish was the language spoken, and Santa Barbara was a close-knit pueblo where people dressed with flair, where music and singing was heard in every home, and where horses were honored and glorified.

And that honor is well-deserved, considering the remarkable evolutionary history of the horse, which originated in North America about two million years ago, long before any conquistador, señorita, or vaquero ever stepped foot here.

Heading into Fiesta’s 94th annual Desfile Histórico—one of America’s largest and most breed-diverse equestrian parades—ponder this thought: Modern humans originated in Africa about 300,000 years ago and first made their way to this continent between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago over the Bering land bridge between Russia and Alaska. But the horse—Equus caballus by its scientific name—is actually from here, a true native, that has managed to successfully adapt and survive on this planet for almost two million years despite great odds.

That’s one spirited animal.

Of course the Old Spanish Days founding fathers—who were determined to include a world-class equestrian parade in the first Fiesta in 1924—would not have known that the horses they so revered were actually native sons and daughters. Science had not quite pinned down the evolutionary lineage of the horse by then.

But fossil records for the horse are among the most well-documented and well-studied in the world. When mitochondrial DNA analysis showed up on the scientific scene in the 1970s, things got even clearer.

Researchers say that the horse family originated about 55 million years ago, but the genus Equus — the modern-day horse — first originated 1.8-2 million years ago in the Great Plains of North America. These horses, which looked and behaved like the horses we know today, were single-hoofed, herd animals that grazed on vast, open grasslands and were built for speed.

During that two million year span, some horses—including a long-headed Equus species endemic to the area we now know as California—decided to pack it up, perhaps looking for greener pastures, and migrated north, over the Bering land bridge into Eurasia.

Good thing they did, because that wanderlust saved the horse species.

Paleontologists determined that about 8,000-10,000 years ago, a massive extinction took place in North America, wiping out many mammals. They believed that horses lingered here until about 8,000 years ago. Those horses that had hiked across the Bering land bridge were the only Equus caballus survivors. They went on to build Alexander’s empire, to fight battles with the Romans, and, through up-breeding, to evolve into the fine breeds we know today. Some of them would become protein for the European and Asian diet. Some pulled the farmer’s cart to market for thousands of years.

And some would come back home.

The Spanish brought many things with them on their voyages to the New World. In their arsenal: their religion, language, culture, and weapons and the mighty horse. In Spain, both the Christian and the Moor doted on their horses. Later explorers like Columbus and Cortés relied fiercely on their steeds, using them for work and transportation and to dominate the indigenous people they encountered living here, who had never seen a horse. According to multiple accounts describing the conquest, the Spanish spread rumors that horses were magical beasts to be feared.

“Horses were certainly not the only reason for the conquest of the Americas—disease, civil war and steel weapons were probably more important in the long run,” according to the American Museum of Natural History. “But in early encounters, horses were an intimidating and unstoppable force. Hernán Cortés, who led the conquest of what is now Mexico, is said to have claimed, ‘Next to God, we owed our victory to the horses.’ … The Spaniards wanted to keep the power of horses for themselves—and with good reason. When Native peoples acquired horses … they quickly became superior riders and used their horses to fight off the European invaders for years.”

Over the centuries, the horse population in the Western Hemisphere skyrocketed.

“The Spaniards were bringing these horses back into a landscape that they were already acclimated to,” explained paleontologist Jonathan Hoffman, PhD, the Dibblee Collection manager of earth science at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Hoffman is working to curate and build the museum’s geology and paleontology collections at its Mission Creek campus, where an excellent display covers the lineage of the horse. “Here they were, coming back 10,000 years later to that open, grassland environment they loved and thrived in,” he said.

In the 2015 book The Horse: The Epic History of Our Noble Companion, journalist and author Wendy Williams painstakingly pieces together the 56-million-year evolutionary horse puzzle. “The horses brought back to the New World in the 1500s by Europeans lived long and prospered—on both the South American pampas and on the North American plains. A few escaped horses burgeoned …. In only a century, the hundreds of imported horses quickly numbered in the tens of thousands. They seemed to be perfectly at home.”

By the late 1700s, the Spanish brought horses to California for use at their missions and ranches. By 1800, according to Deb Bennett, author of Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship, the population reported by the California missions had grown to 24,000 horses. Californios during the Spanish and Rancho periods became famous worldwide for their riding skills and for their tremendous love of their horses.

It’s no wonder Old Spanish Day’s first presidente and parade chair, Santa Barbara pillar Dwight Murphy, insisted that the horse be cast in the spotlight during the opening festivities.

In Edward A. Hartfeld’s biography of Murphy, California’s Knight on a Golden Horse, we learn that only $200 had been budgeted for that first parade in 1924, so Murphy quietly contributed $10,000 of his own funds to ensure that the first Fiesta would exceed all expectations and outshine that parade down in Pasadena devoted to roses. Hartfeld’s own father, John H. Hartfeld, had worked with Murphy. The younger Hartfeld writes, “For the first parade, local VIPs and some Spanish descendants were loaned beautiful Thoroughbred horses adorned with silver saddles from Murphy’s Los Prietos Ranch …. The parade was an unforgettable equestrian event, in large measure due to the marvelous collection of fine horses from around the state and the authentic costumes of the parade participants. Nothing like it had ever been seen in this country.”

Records show that the first parade was attended by some 8,000 spectators. This year, we’re expecting 150,000-200,000 attendees. And we’ll see upward of 650 horses, including Andalusians, mustangs, Appaloosas, paints, quarter horses, Thoroughbreds, and, of course, the striking golden palominos, with their beautiful cream manes and tails, which Murphy brought back from near extinction at the breeding ranch he operated off San Marcos Pass.

This year’s parade lineup is the responsibility of Old Spanish Days parade chair Will Powers, whose grandfather Wayne Powers preceded him as parade chair for several decades. Powers is focused on many things leading up to the parade, like vetting the hundreds of entry requests that come from all over the nation. Will Powers admits he’s no equine historian, but he knows one very important rule about horses in parades: “Don’t freak them out!”

“Some people think of horses as big dogs, but horses are flight animals, and they’ll take off if they get spooked,” said Powers. “This parade is a mile-long trek, uphill, with the road narrowing in on them, and lots of noise and chaos and big crowds. They have to be able to handle the terrain.”

They may all belong to the same species, but Powers said horses are often unique in their personalities and dispositions.

“Horses start to emulate their owners’ personalities: You’ve got the divas, the sweethearts, the shy ones, the proud and stubborn ones,” said Powers, who will have a team of 75 volunteer marshals along the parade route, and 40-plus outriders who are expert equestrians who come to the rescue if the horses get spooked or sidetracked.

William Luton Jr., an avid horseman who was presidente in 1988, is a ninth-generation Santa Barbaran, and a descendent of the first commander of the Spanish Presidio, José Francisco Ortega. Luton’s appreciation for the horse is deep-rooted.

“They used to says ‘Good horse, good dog, good wife; you can’t ask for any more in life,’” Luton said with a chuckle. Growing up here, he said, Fiesta felt like one big, long, successful family gathering, with all the colorful stories and occasional shenanigans to keep things interesting. “We used to have a group of Texas longhorns in the parade. We’d load them up in the morning and dump them down on the beach, by Fess Parker, and they’d lumber up State Street, with their massive horns swaying. It was quite a sight to see. That was a long time ago. We had to stop that. Back in the day, you’d see a rider take his horse into a bar and order a margarita. Me, I’d never do that. I met my waitress at the door.”

It’s true. Some things have changed.

“Horses used to be a way of life here, but they are more of a hobby for people now, an outlet for recreation,” commented Graham Goodfield, owner of Los Padres Outfitters, whose grandmother rode in the first Fiesta parade. Goodfield’s Carpinteria operation will provide 30-40 horses that we’ll see in Friday’s event, including a buckskin quarter horse ridden by this year’s presidenta, Denise Sanford.

Goodfield, a voting member of the Rancheros Visitadores, and his wife, Hannah Goodfield, are working to keep many of the early equestrian traditions alive, and that starts with appreciation of the special relationship between humans and horses. “A true horseman respects his horse and treats him with the utmost care. Santa Barbara was really the mecca for a kind of horsemanship that spread all over the country, and it’s really something worth preserving today.”

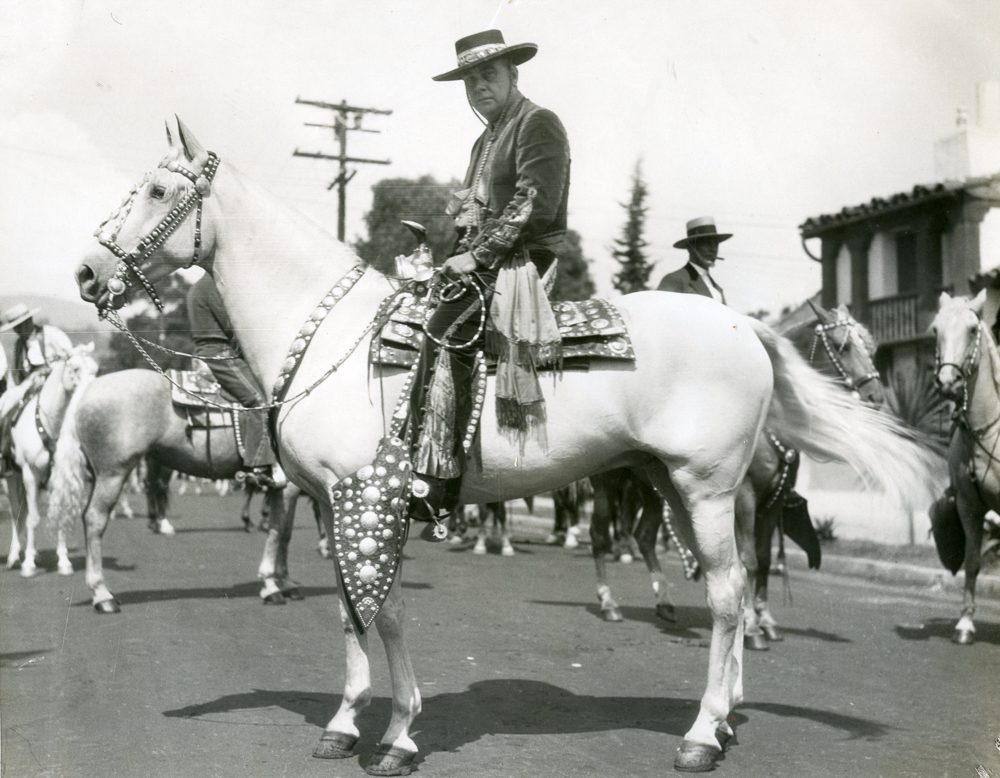

Fiesta parade in 1928

From the scientific perspective, horses can teach us many things, Hoffman said.

“The horse has given so much to our civilization. … Some don’t realize the complexity of their contributions,” Hoffman said, explaining that along with helping us build our communities, excellent fossil records have helped us understand how our planet has evolved.

Early scientists who had attempted to solve the puzzle of the horse’s true evolutionary history made a few blunders along the way. As Williams explains in The Horse, it was once thought that “the horse was a gift from the Old World to the New”; the horse, however, was actually a gift to the Old World from the New.