Lords of the Rings: Will Steel Nets Save Montecito?

Well-Funded Nonprofit Seeks Emergency Permits to Block Debris Flows

In the wake of last winter’s Thomas Fire and 1/9 Debris Flow, greater Santa Barbara was stunned. We had just witnessed back-to-back forces of nature kill 25 people, destroy more than 100 homes in the county, and traumatize those families who survived. Many of us didn’t know what to do, but we knew we wanted to help.

In the months that followed, thousands of volunteers took action, handing out food, digging out homes, and helping survivors find new places to live, fill out disaster-relief paperwork, navigate insurance claims, and talk with therapists about their life-altering traumas. Others donated equipment and services. Some launched spur-of-the-moment nonprofits, to which many more wrote checks to help keep the recovery work alive.

Now, as the first rains of what looks like an El Niño winter have arrived, a well-connected, privately funded group of women and men, many of whom live in Montecito, has proposed an ambitious plan ahead of the coming storms.

They call themselves The Partnership for Resilient Communities, and they first reached out to community leaders — from emergency responders to elected officials — asking: What can we do to help? Then came their bigger question: What can be done to stop a debris flow from happening again? The answer, of course, is nothing.

But perhaps, they decided, something could be done to capture and slow a debris flow, should another come down from the steep canyons above Montecito. After much research, the partnership settled on a Swiss-born technique: ring nets.

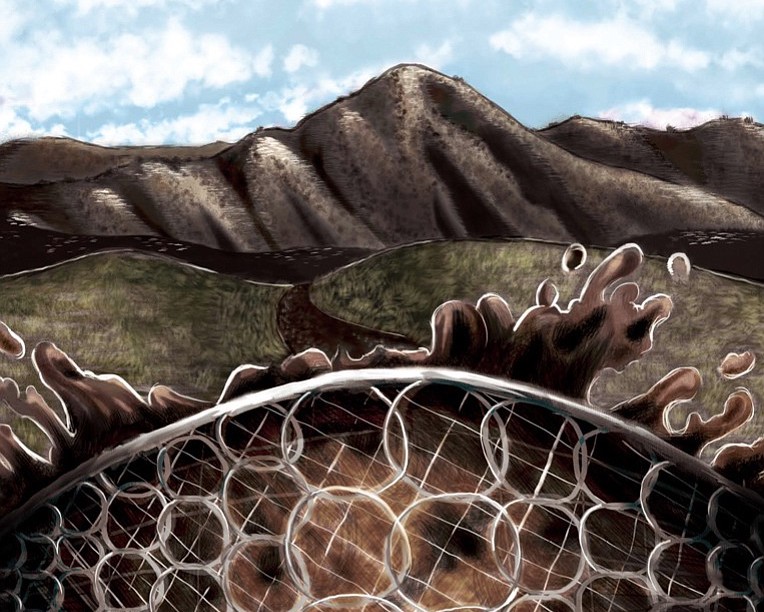

The plan proposed is to anchor ring nets — high-tensile steel-wire barriers — across the upper reaches of Hot Springs, Cold Spring, San Ysidro, Buena Vista, and Romero canyons in the hopes of trapping boulders, branches, and thick mudflow that could be set loose by intense rainfall. But what seemed at first glance a straightforward mechanical solution to a public-safety concern turned out to be anything but.

To accomplish their plan in short order — right now, they’re aiming to install 16 nets by the end of the year — the partnership must secure permission from the U.S. Forest Service and a handful of private residents who own the canyon parcels where the ring nets look to be most effective. More challenging, the partnership must also pull emergency permits from several regulatory agencies, including Santa Barbara County Flood Control, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which must consult with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service, respectively, because Montecito’s wild canyons and creeks are critical habitat for the red-legged frog, federally listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, and the venerable, federally endangered steelhead trout.

“There is still rock moving up there in the mountains,” said the partnership’s spokesperson, Pat McElroy, 65, who retired as the City of Santa Barbara’s longtime fire chief on March 17. “Essential to all of this, including getting permission and all the permits, is the urgency of it. We’re trying to get ahead of winter.”

The Partnership

As McElroy tells it, the partnership took shape within a week of the January 9 tragedy when he got a call from Montecito resident Brett Matthews. McElroy and Matthews had worked together before. In 2009, as the Jesusita Fire raged along the Santa Barbara mountain front, an inadequate contract had rendered nearby Santa Maria Airport off-limits to air tankers, forcing pilots to refill on fuel and fire retardant out of the area. Fire chiefs countywide were livid, wondering how many of the 80 destroyed homes could have been saved. Matthews had connections to former 3rd District Santa Barbara county supervisor Willy Chamberlin (a Republican from Los Olivos) and then-congressmember Elton Gallegly, of Ventura County. Pressure was applied, McElroy remembers; since then, Santa Maria Airport has been open to tanker traffic year-round. Last year, he added, more than half of all the retardant dropped on California wildfires was flown out of Santa Maria.

Matthews was also on the phone with Gwyn Lurie, with whom he had served for several years on the Montecito Union School District’s Board of Trustees. Her husband, Les Firestein, a builder and a longtime television writer and producer with hits such as The Drew Carey Show and In Living Color, joined the conversation. Another Montecito resident, Montecito Planning Commission Chair Joe Cole — a minority shareholder and former publisher of the Santa Barbara Independent — was also part of the original partnership.

“All of us were just like everyone else,” Lurie said. “We were horrified. We were trying to make sense of it and do what we could.

“Montecito is full of people not used to feeling out of control,” she added.

The partnership soon discovered that Santa Barbara County government leaders were running on fumes, overwhelmed by the monumental cleanup of Montecito, Summerland, and Carpinteria, while scrambling through unfamiliar federal channels in an attempt to recoup recovery expenses. To help, the partnership privately funded a temporary public position for consultant David Fukutomi — formerly with the National Guard’s Homeland Security Institute and the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services — to work in the office of County Executive Officer Mona Miyasato and her second in command, Matt Pontes.

“[Fukutomi’s] experience helped us tap into grant programs that were different than the wildfire-driven stuff we were already used to,” Pontes said. “There were avenues we didn’t know about, and he’s been a world of help.”

About the ring net plan, Pontes said, “We’re for it … super excited. If it were a normal governmental process, it would take years to get these up, and we don’t have that kind of time. We’ve seen the [watershed] channels, and they’re loaded [with boulders]. We anticipate aggressive evacuations this winter.”

The partnership — with seed money donated by wealthy Montecito homeowners, including real estate developer Herb Simon and cell-phone industry pioneer Craig McCaw — also flew in consultant James Lee Witt, who was the director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under President Bill Clinton. Witt’s ties to Santa Barbara date back to 2010, when he worked with Kinko’s founder Paul Orfalea to beef up the county’s Office of Emergency Management. This time around, Witt has been an on-call advisor and sounding board as the county put together its recovery strategic plan, according to Pontes.

Meanwhile, other members of the partnership, who include political consultant Mary Rose and communications executive Alixe Mattingly, a former deputy press secretary for presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush and a boardmember with Direct Relief International, Lotusland, Laguna Blanca School, and MOXI, The Wolf Museum of Exploration + Innovation, have helped to raise awareness — and money — for the ring net plan.

Firestein took on the job of researching what solutions other communities living in the paths of debris flows had found. His first discovery was Japanese sabo check dams, which have been successfully used for hundreds of years. But building their concrete walls and downstream beam grids, Firestein explained, would take years and raise major environmental concerns. Sabo dams for Montecito, he said, were “a nonstarter.” He also researched PineBind, advertised as a natural stabilizer that can be crop-dusted across denuded hillsides, plus a variety of seeding and mulching strategies, most of which were very expensive and unreliable.

Firestein eventually came across ring nets manufactured by Geobrugg, a company based in Switzerland. It turns out that Kane GeoTech, a Stockton-based geoengineering firm, had engineered 55 Geobrugg nets since 2004, mostly in the western U.S., including a fencelike system to capture landslides above Highway 1 in Big Sur and five ring nets across barrancas in Camarillo Springs, as safety measures for a community beneath mountains scorched by the Spring Fire of 2013.

Geobrugg’s ring nets seemed like the best fit, Firestein said, plus Kane GeoTech had a good track record. A few months back, the Montecito partnership hired founder Bill Kane and company vice president Mallory Jones to hike and map Montecito’s five prominent canyons — Hot Springs, Cold Spring, San Ysidro, Buena Vista, and Romero — to pinpoint where a series of ring nets, located upstream of existing debris dams, could potentially trap the beginnings of a debris flow. They found more than five dozen suitable locations, mostly at canyon pinch points along the upper reaches of the five watersheds. Then the partnership hired Colorado’s BGC Engineering to evaluate Kane’s plan. Their team, which included Dr. Matthias Jakob, a leading expert in debris-flow risk assessment and author of a standard textbook on the topic, issued their own assessment of the dangers.

In its August 31 letter to Suzanne Elledge, a planning and permitting expert who is voluntarily guiding the partnership through the project’s regulatory hoops, BGC stated, “Urgent action is needed to protect life and property in Montecito from the impacts of future debris flows. The January 2018 debris flows did by no means remove the hazard or return the watersheds to pre-fire conditions. The likelihood of debris flows this winter remains high.”

The Opposition

Not everyone agrees with these conclusions, however. At a community forum hosted by the Santa Barbara Urban Creeks Council, UCSB geologist Ed Keller said there’s no way to know for certain if heavy rains will spur another deadly event, adding that anybody who says they do know “is just guessing.”

Urban Creeks Council Boardmember Louis Andolaro was opposed to the emergency nature of the plan, calling it an “end run” around a properly reviewed permitting process. He also said installing the nets could cause “massive site disturbance” to critical steelhead habitat and that the estimated price tag of $5.5 million to purchase, install, maintain, and clean out the nets seemed too low.

Speaking at the same forum, Natasha Lohmus, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, called the barriers “gill nets for mammals” that could trap deer, bear, coyote, and other large mammals that commonly travel along streambeds.

McElroy has taken issue with the gill net analogy, calling it inaccurate and inflammatory at best, malicious and pejorative at worst. Geobrugg followed up with an October 9 letter from its California regional manager, Saleh Feidi, who wrote, “The reference to ‘gill nets for mammals’ is completely without merit [or] evidence, photographic or anecdotal, and mischaracterizes our product intentionally. This reference is defamatory in comparing our product, which serves to protect habitat, with an ocean-based system designed to kill and capture fish. We have no recorded incidents regarding animal death [or] injury.”

McElroy explained that the ring nets can be custom designed with larger-diameter rings along the bottom and sides, through which animals can pass, and positioned so that the bottom row of rings is suspended above the surface of the creek, to avoid disturbing fish and frogs while allowing silt to pass through on its way to the beach.

“We need to get permission for all this work,” McElroy added. “Nobody is trying to go around the regulatory process, and we’re looking at this as a temporary solution until the forest grows back.” Biologists estimate that new grasses, shrubs, and trees could stabilize the mountainsides in five years, give or take, depending on how much rain we get.

“Our North Star is up there on that mountain,” McElroy said. “We’re looking at the best technologies that exist. The Swiss nets seemed the best fit for our condition, which includes environmental concerns.

“There is going to be opposition,” he added. “To them I say, ‘What’s your plan?’”

At the forum, Lohmus also pointed out that Montecito’s stream channels, scoured by the debris flow, are now an empty canvas, so to speak, for creekside landowners to replant with native trees, such as willows, which stabilize riparian corridors and provide optimum wildlife habitat.

The partnership’s Brett Matthews seemed to take that suggestion to heart. “Let’s call it a five-year plan,” he said in an interview, explaining that temporarily putting up debris nets could protect downstream channels from further damage as plant life returns to the mountainsides. At the same time, property owners could help by planting willows and other native species as Santa Barbara County Flood Control moves ahead with its plan to renovate existing Montecito debris basins.

Matthews added that the partnership is currently working on creating an escrow account dedicated to promptly cleaning out the debris nets, if necessary, and “insuring the risk,” he said, so that the property owners of the canyon parcels won’t be held responsible for accidents during construction or cleanout, for example, or in the event of net failure.

Meanwhile, the county’s emergency leaders are refining their evacuation strategies throughout Montecito, Summerland, and Carpinteria. “And we’re going to go in and touch up our debris basins,” said Flood Control’s Tom Fayram, adding that his team will have cleanup and maintenance contracts lined up with outside companies so that, if the mountains start to move again, “literally, we could call somebody at 6 a.m. and be working at 7.”

On ring nets, Fayram said, “We’ve been talking to [the partnership], but we’re not hooked into that as a cooperator, per se. We don’t want to get into a scenario where their work and our work are in conflict. But right now, it looks like we won’t be getting in each other’s way.”

County Supervisor Das Williams, whose district includes Montecito, Summerland, and Carpinteria, said, “I’ve spoken with Tom [Fayram] and with [the Department of] Planning and Development. We’re in agreement. We’re not going to create barriers for [the ring net proposal]. We’re going to facilitate them.” Williams added that in the spirit of removing red tape during recovery from the fire and debris flow, “If there are worthwhile ideas proposed by anybody, we [the county] would like to help, or at least not get in the way.”

Red Light, Green Light?

The partnership also hired Storrer Environmental Services to put together a biological report on the watersheds and take a hard look at Kane’s installation plan. John Storrer and his colleague Jessica Peak spent weeks in the Montecito mountains, coming up with ways to avoid or minimize any environmental disturbances that could surface if and when the ring net project is given the regulatory green light.

Storrer and Peak’s report — an indispensable part of the permit application process — suggested relocating a few of the nets to avoid tree removal and excavation during installation. Also, they’ve recommended a stand-down order to protect human lives if intense rains hit while crews are in the canyons. Another key condition would be to prevent any concrete slurry — used to anchor the nets into the bedrock — to flow downstream, as it could harm wildlife and habitat deemed critical to the recovery of steelhead, red-legged frogs, and possibly even federally endangered tidewater gobies, a small fish that breeds in brackish water but is known to tolerate freshwater far upstream. To mitigate the potential blockage of steelhead movement, nets that fill up after a debris flow would need to be promptly emptied.

If the proposal is approved, expert biologists will likely monitor the work, including the movement of manpower and materials along existing fire roads and trails, and quite possibly a helicopter and a walking backhoe, which can creep like a four-legged spider through rocky narrows.

With the partnership now putting the final touches on its application package, the ambitious proposal will soon rest with a handful of regulators who will consider its fate on a very tight deadline.

“I’ve consulted on construction projects for 35 years, some of them in active streams,” Storrer said. “I’ve not seen anything quite like this.”