The Housed and the Homeless and the Commons: Part 2

Learning to Share Requires Leadership

While we and the homeless are going to have to learn how to share the “commons” (common areas) leadership will have to come from City and County government, both of which are facing serious staffing and financial strains created by people living on our streets. The city and county of Santa Barbara do a lot in addressing this problem, including shelter, food, medical care, showers, clothes laundry, and RV parking. Our municipalities seek federal grants for homeless services (the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, provides financial assistance grants to cities through the California Department of Housing and Community) and work closely with nonprofits providing services. Notwithstanding, it is the legal arena that will ultimately determine the fate of State Street.

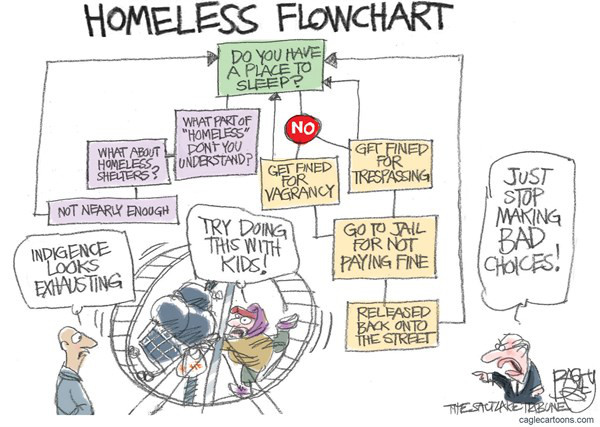

The courts, which have ensured the rights of homeless people to solicit for money, have added the right to sleep on the street if the municipality does not provide sheltered beds. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that in the absence of adequate sleeping facilities it is “cruel and unusual punishment,” violating Eighth Amendment rights, to cite or prohibit homeless persons from sleeping in public. Santa Barbara is responding to this mandate by building a village of 40 “tiny homes” (houses of about 128 square feet with bed, bath, and kitchen) for the city’s most vulnerable homeless. Regardless of legal mandates and the fact that the alternative is to turn our public streets into bedrooms, this is obviously the right thing to do.

Homeless behavior at odds with the traditional norms for the commons will, despite sheltered sleeping quarters, continue to exist. Balancing it with acceptable public behavior is in the hands of city laws and law enforcement infrastructure. City ordinances need to be reviewed for compliance with legal rights, and we need to support and expand the way Santa Barbara goes about policing homeless behavior.

We have an excellent police department. However, not all police officers are suited for enforcing homelessness ordinances; it takes a certain temperament and training. Officers who volunteer for the duty and are trained in dealing with “street people” have been proven to be more effective. They are trained to distinguish between the different kinds of homeless and how to relate to them. In doing so, they are able to make the appropriate responses, including citations, arrests, referrals to assistance programs and medical attention, eviction from the street, and/or referral to Homeless Court (Restorative Court in Santa Barbara).

Restorative Court is a voluntary program offered to chronically homeless people as an alternative to entering the Superior Court criminal system. It is based on the premise that superior courts and judges are not equipped to deal effectively with homeless legal infractions. Its function is to help chronically homeless individuals achieve self sufficiency. Santa Barbara’s Restorative Court is a spot-on collaborative effort between the police, court system, health care, and social services agencies. It sees those sent to it as clients, not criminals, and places them in detox, housing, or work programs in lieu of jail. In the event those taken into the system refuse treatment, depending on the offense, they can be fined $400 to $1,000 and/or incarcerated for 90 days or longer.

If preserving the decorum of the commons is a priority, Santa Barbara’s program needs to be expanded and focused more intently (with more officers) on patrolling State Street. The program, which interacts directly with the homeless on State Street (and the downtown area), consists of two sworn officers and two part-time non-sworn personnel. One of the non-sworn officers acts as a liaison with homeless services (such as lodging, medical, mental health, substance abuse, et al); the other works directly with referrals to Restorative Court and re-uniting people living on the street with their families. In addition, Restorative officers coordinate, when appropriate, with a variety of downtown policing services such as Neighborhood Policing, Ambassadors communicating with downtown businesses, and Volunteers in Policing who interact with everyone using the commons by answering questions, giving advice, and when necessary calling sworn officers to deal with disruptive and/or criminal behavior. This is an exemplary, understaffed program in need of more money.

To effectively deal with the homeless issue in the commons, our community needs to have the political will to pay for a “constant” Restorative Policing presence on State Street from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily. It’s not realistic (or fair) to expect two officers working with two non-sworn personnel to change behavior. Chronically homeless people will both disregard being talked to by the police and tear up or throw away citations. There has to be on-the-spot follow-through capable of deciding if there should be an immediate arrest or whether the offender is likely to honor a referral to Restorative Court for social service referrals.

In addition to alternative courts and policing, public meetings should be organized to educate residents, explain recent court opinions, and “teach” us how to interact with street people. City officials will also have to try and meet with the homeless population, explaining the laws governing acceptable public behavior. Assuming a lack of attendance by homeless people at such meetings all of Santa Barbara’s homeless laws, explaining acceptable legal behavior, need to be posted. Signage, or posting a warning, is a proven legal technique for communicating with the public while simultaneously insulating the city (and county) from actionable liability based on aberrant homeless behavior.

“Solving” this problem to everyone’s satisfaction is impossible. There is no “silver bullet” for this kind of behavior. Homeless people will continue living among us and using State Street. Behavior, however, can be humanely normalized without brutalizing the homeless. This requires adopting a comprehensive approach along the lines outlined above. The approach is not optional if we want to preserve our commons. Without institutionalizing social services, creating more policing trained to deal with homeless populations, adequately funding and staffing Restorative Court, and a relentless program of seeking state and federal grant assistance, we will be left with deviant behavior on a declining State Street.

The choice is ours.