Our Blue & Green Adventure Guide 2019

The ‘Santa Barbara Independent’ Presents Its 21th Annual Ode to the Great Outdoors

By Indy Staff | Published June 12, 2019

Twenty years ago, the Santa Barbara Independent launched its inaugural Blue & Green issue as a guide to adventure

and fun in the great outdoors. Over the decades, it’s evolved from a one-stop shop for the best hiking,

mountain biking, and climbing locations into an annual collection of stories about backpacking trips,

sailing excursions, island explorations, kayak expeditions, and poison oak sagas.

This year’s spread includes a little bit of everything, from John Zant’s memoir of walking the county’s entire coastline

in 1988 and an author who found solace through backpacking to the joy of watching leopard sharks near

Isla Vista and hiking into the hills above Carpinteria. (Plus this great photograph, and the one

on the cover, by Chuck Graham of pronghorn antelope amid the Carrizo Plain superbloom.)

As usual, there’s a full guide to outdoor-focused companies that are standing by to make your next trip happen.

Please enjoy, and then go outside.

Conquering the Santa Barbara County Coast

Remembering a Dozen Days of Hiking from the Santa Maria River to Rincon in 1988

Conquering the Santa Barbara County Coast

Remembering a Dozen Days of Hiking from the Santa Maria River to Rincon in 1988

by John Zant

The author walking on Hendry’s Beach

On August 8, 1988, I stood where the Santa Maria River meets the Pacific Ocean at the northwest corner of Santa Barbara County. I was about to start walking south and east along the coast for 110 miles — the entire length of the county shoreline.

It would take me 12 days, and after each day’s hike, I would write 1,200 words or so about what I saw, heard, and felt. My accounts, along with pictures from different photographers who accompanied me, appeared daily in the Santa Barbara News-Press starting on August 10.

For logistical reasons involving the transmission of my stories and the processing of photos taken in the North County, the first five days of the walk required two days before appearing in the paper. Then I took a day off, and each remaining report was published the next morning.

Here’s how it went down.

Day 1

Guadalupe Dunes to Point Sal (6 miles): Under overcast skies, a cold wind blew onshore. The surf was turbulent. The beach was deserted except for a couple of fishermen and two brave surfers. After a mile, the strand was interrupted by Mussel Rock, a large formation jutting out to the sea.

My path necessarily took me along rocky ledges, dropping down to a few pocket beaches, before I reached the primitive state beach at Point Sal. The scenery was Big Sur–like in its rugged beauty. Wildlife abounded along the cliffs and on the offshore Lion Rock. A sea otter, unmistakable as it floated on its back, appeared at the southernmost limit of its range.

I typed my story to the rhythm of the waves and slept on the beach. Photographer/courier Karl Mondon drove a winding seven-mile road from Santa Maria to meet me in the morning. The road has since washed out and is only a hiking trail, sometimes closed, making Point Sal even more inaccessible.

Day 2

Point Sal to Ocean Beach County Park (15 miles): My editors had secured permission for me to proceed into Vandenberg Air Force Base. I was told that an escort would meet me at the gate. I took this to mean an entry point near the shore. The base commander apparently had meant the main gate several miles inland.

John Zant trudges the county coastline near the Guadalupe Dunes, where he started his 1988 walk.

An interesting development that aims to alleviate some pressure is that high schools in California are now being measured on how well they are preparing students for college and career. The state now monitors the “College and Career Readiness Indicator,” pushing secondary schools to offer and expand pathway programs that put students on track toward specific careers, whether requiring a college degree or not. The state has invested $500 million toward the cause.

So when I made a beeline to the beach between Point Sal and Lions Head (a prominent outcropping on the north coast of the base) — sans escort — I was officially a trespasser, and airmen were deployed to find me. I encountered them at Minuteman Beach.

They were working with shovels around the wheels of a jeep. It had been stuck in the sand, sinking deeper when the wheels spun. “Are you the missing civilian?” the leader of the search party asked. Then he added: “You do not see this.” Upon the arrival of my escort, Mike McElligott of the VAFB Environmental Task Force, I was free to go.

What struck me about the miles of beach and dunes that lay ahead — next to hidden missile silos — was their pristine condition. Not a scrap of litter.

“Take away the missiles,” McElligott said, “and condos go up right here.” He steered me around the breeding area of the rare snowy plover.

Day 3

Ocean Beach to Jalama Beach County Park (20 miles): After spending the night in Lompoc, I was rested for the biggest day of the trek. My escort joined me again. No photography was allowed once we left the public area around the mouth of the Santa Ynez River. There were sensitive military installations, including a complex built for West Coast Space Shuttle launches. The program was scrubbed after the Challenger disaster.

McElligott was more interested in the rich biodiversity of the region. The ecologist pointed out species like the three-spined stickleback, a small fish that existed only in three coastal creeks. Sea mammals flourished offshore.

We walked along the railroad tracks above sheer cliffs that plunged to the ocean. At Point Pedernales (a k a Honda Point) were some rusted remains of the 1923 naval disaster where seven destroyers ran aground and 23 sailors perished. South of Point Arguello, we could walk along the shore, bisected by eight coastal canyons. The sand was coarse and tiring to walk on.

The prospect of a Jalama burger pushed me through the last mile beyond the boundary of VAFB. It was the most delicious burger I ever tasted.

Day 4

Jalama Beach to Point Conception (6 miles): The county park was teeming with visitors. Many waited in a long line of vehicles outside the entrance. Not all would secure a camping spot. But after I walked a mile south toward Point Conception, the beach was deserted. I had permission to enter Cojo-Jalama Ranch, the private property surrounding the point. Trespassers were dealt with harshly.

I had a rare opportunity to check out the lighthouse, which sits below a bluff and cannot be seen from the passing Amtrak trains. I spent the moonless, starlit night in an abandoned outbuilding. At 2 a.m., I went to the bluff top to look out to the sea surging all around me at this nexus of west- and south-facing shores. It was an ethereal experience I did not have the words to describe.

The Chumash Native Americans who populated the coast for thousands of years were said to have journeyed to this special place at the end of their lives. (I was overjoyed by the news that Cojo-Jalama has been purchased and donated to The Nature Conservancy for preservation. See “The Last Perfect Place” in the April 25 edition of the Independent.)

Day 5

Point Conception to Gaviota (14 miles):The sea had gone from wild to glassy on the south side of the point. I was met by Mike Drury, Hollister Ranch security officer, as I walked along the shore. It was his mandate to keep outsiders from encroaching on the private land, which essentially made this long, sandy stretch inaccessible, inasmuch as there were natural barriers to beach walkers at both ends. The worst invaders, Drury said, were poachers who sought wild deer and boar.

A way to provide public access to the beaches is a current topic of controversy. The strand was clean and unspoiled 31 years ago. There was one family, who owned property on the ranch, enjoying a day on the beach all by themselves. At the end of the day’s walk, I realized what a privilege it was to have seen 50 miles of shoreline off limits to most people.

I later met Jim Blakely, a naturalist and explorer who had done the same walk by himself. How did he manage it? “I had a hard hat and a clipboard,” he told me. “With those, you can go anywhere.”

The author’s list of adventures includes topping Mt. Whitney in 1988 and winter backpacking with llamas in 1987.

Day 6

Gaviota to El Capitán State Park (14 miles): From now on, there would be fewer moments of solitude on my journey. Three popular state parks were along this stretch. The middle one, Refugio, was postcard-perfect. It was along here that I started to pick up tar on the soles of my shoes (I wore old running shoes in anticipation of this).

I heard this telling comment from Roy Loomis, who lived on a ranch up Arroyo Hondo Canyon: “I remember I used to sit around here and not get tar on my pants. That was before all these ‘natural’ oil seeps. Even a dumb cowboy like me can figure out what’s happening. You pressurize an oil well, and it’s going to increase the seeps. Pressure a hose, and it’s going to squirt harder.”

Day 7

El Capitán to Coal Oil Point (9 miles): From the state park, population 800, I headed off to some relatively untrammeled shores. Two miles of them were bordered by Las Varas Ranch, which last December was donated to UCSB. East of Dos Pueblos Canyon, I splashed along between cliffs and an incoming tide. It was a more challenging hike than I expected. Trash littered the beach near the future site of the Bacara resort. “Maybe they’ll clean this place up,” a longtime visitor told me.

Day 8

Coal Oil Point to More Mesa (6 miles): Below the precariously perched Isla Vista cliff dwellings were rusted automobile skeletons and bicycle frames. Goleta Beach was a gathering place for area residents. On the beach below More Mesa, naked sunbathers and Hope Ranch equestrian riders existed in harmony.

Day 9

More Mesa to Leadbetter Beach (6 miles): Fishermen in body boats came ashore with catches of calico bass. A pod of dolphins swam parallel to the shore off Hendry’s Beach. A couple sweeping Leadbetter Beach with metal detectors claimed to have collected $1,900 in loose change over a two-year period.

Day 10

Leadbetter Beach to Butterfly Beach (5 miles): For two and a half miles, the City of Santa Barbara stretches out to the sea between the bluffs of Shoreline Park and the Santa Barbara Cemetery. A couple of rubberneckers at the harbor told me they had met there 50 years ago when “hot dogs were a dime at the Lighthouse” and Max Fleischmann’s yacht and only one other boat were anchored there. British tourists expecting California sunshine and blue skies were disappointed by marine layer: “Now, it’s like England.”

Pronghorn antelope

Day 11

Butterfly Beach to Carpinteria City Beach (6 miles): Around the corner from the Biltmore and the Coral Casino, a bulldozer was grading land around Hammond’s Meadow. Twenty condos would be developed there, but at least three acres of the meadow would be preserved. A Miramar Beach resident described the beachfront homes as “early ramshackle style.”

I wrote, “Like lobsters, they shed their old skins … and become more expensive.” The Miramar Hotel, with its long boardwalk and offshore raft, was still intact and inviting. On the beach below Summerland, famous polo player Memo Gracida rode his pony in the surf.

Day 12

Carpinteria Beach to Rincon Beach (3 miles): The News-Press invited readers to meet me at the end of Linden Avenue and walk with me to the end of my journey. Several hundred showed up.

We left the beach to traverse the Carpinteria Bluffs, another development battleground. Landscape artist Arturo Tello was putting a scene on canvas. Beyond the oil pier where harbor seals hang out, we went back down to the shore. There was a seal wall below the railroad tracks.

The tide was coming in. I made a dash across the sand when a wave receded. The next wave nailed some of the people trailing me. Moses I am not. In the middle of Rincon Creek, I took my last step from the fabulous coastline of our county.

Long Live the Franklin Trail

Historic Carpinteria Route Still Recovering from Fire and Flood

Long Live the Franklin Trail

Historic Carpinteria Route Still Recovering from Fire and Flood

by Chuck Graham

December 2017’s Thomas Fire, followed by the destructive debris flow the following month, left many sections of hiking trails in the coastal Santa Ynez Mountains impassable. From the Cold Springs Trail in Montecito to the Franklin Trail located behind Carpinteria High School, many of the routes still need to be rebuilt, rebooted, and, in some cases, rerouted.

When I hiked the remains of the Franklin Trail shortly after the fire, I could have easily been on a lunar landscape. Ash clung to me from head to toe and as dust devils stirred the lifeless front-country. Originally built in 1913, the 15.8-mile, out-and-back route is one of the area’s oldest established trails. It consists of four phases. The last two — Phase 3 and 4 in the upper reaches — were decimated by the fire and heavy rains.

Shortly after hiking to the top to see the aftermath firsthand, it was difficult to imagine it ever recovering. The longer sections of switchbacks had parts that were completely washed out. There was a lot of loose, chunky scree and unstable ground along the final 2.7-mile stretch to the Santa Ynez crest, the steepest part of the entire trail.

However, after recently speaking with Mark Wilkinson, executive director of Santa Barbara County Trails Council, there is plenty to be hopeful for regarding access to the higher elevations of the scenic Franklin, which tops out at 3,720 feet. “Fundraising since the fire has gone well,” he said.

This isn’t the first time the trail is being revived. It was swallowed up 40 years ago by a changing landscape of private properties and agricultural growth in the Carpinteria Valley. It became an afterthought, eventually choked off by overgrown chaparral.

However, over the last decade, community nonprofits such as S.B. County Trails Council, Friends of Franklin Trail, Montecito Trails Foundation, Los Padres Forest Association, and the S.B. Sierra Club Group have collaborated with the Los Padres National Forest to restore the historic Franklin Trail and reconnect it with the rugged backcountry.

“Before the fire, we just needed a few retaining walls to complete it,” said Wilkinson. “Now we need a lot.”

To donate to the Franklin Trail, go to sbtrails.org.

Author Dustin Waite Finds Meaning on the Trail

Los Padres National Forest Featured in Appalachian Trail Memoir

Author Dustin Waite Finds Meaning on the Trail

Los Padres National Forest Featured in Appalachian Trail Memoir

by Richie De Maria

Dustin Waite | Credit: Courtesy

Where does one go when they’re at a crossroads between jobs, relationships, and life paths? Into the woods, of course. In External, former Santa Barbara resident Dustin E. Waite takes readers on his journey on and off the Appalachian Trail. It’s an enjoyably readable, often funny expression of Waite’s navigation through life’s uncertainties; a story of how he finds answers in wildernesses across the world and in the hearts and minds of the people who he meets along the way.

For S.B. readers, the book holds a special attraction, with several passages detailing Waite’s trips onto trails in the Los Padres National Forest. Born and raised in Iowa, Waite moved out to Santa Barbara to work as a geological consultant. He soon discovered that he loved the outdoors.

External by Dustin E. Waite

“It was an awe-inspiring thing,” he recalled of seeing the Santa Ynez Mountains for the first time. “I was so impressed with everything, and it kind of sparked the interest, really lighting that fire in me to learn more about the backcountry and hiking.”

There’s more than a little bit of Santa Barbara in Waite’s book. Through the pages, we follow him up familiar front-country routes like La Cumbre Peak and toward more remote backcountry mountains like Madulce Peak. Waite invites readers along on his friends’ annual Death March, a multi-day jaunt through arid stretches of Los Padres wilderness; and equally, to urban haunts like Handlebar, his favorite coffee spot, which gets a shoutout in text.

Whether or not one is familiar with our area’s wild lands or backpacking generally, the book holds plenty of appeal to the average reader with its very relatable and humbly astute observations on life’s many trials and tribulations.

In many ways, the book is just as much about relationships, in all their joys and confusions, as it is about the wilderness. “We develop relationships at every switchback of our lives,” he writes in External. Many can find much to relate to in Waite’s words on romantic misadventures, company layoffs, and all-entailing existential quandaries. We read how not great tragedy, but the accumulation of life’s more routine disappointments and sadnesses prompt Waite to explore life’s bigger questions in the solace of the woods: “I probably didn’t necessarily intend for it to be a big six-month reflection, but pretty shortly after beginning, you realize that’s what this thing is. It’s a time to just think, with 15-20 miles each day in between to reflect and think about life.”

On the Appalachian Trail, Waite runs into bears, bugs, and an even more dangerous personal health crisis, but his biggest takeaway is the people he meets. “When anyone asks me what’s your favorite part of the Appalachian Trail, I say it’s the people,” he said. “I know everybody wants to talk about bears or the best views, but if you don’t walk away saying the people you met, then we had different hikes. I met some of coolest, most influential people I’ve ever met on the trail, from every life scenario. I met people who had just lost a parent, just got over cancer, just went through a divorce. Not to sound too cliché, but you have to have a little caution because you realize you don’t know somebody’s back story.”

It’s also very much a book about embracing the now — a book about seizing the life you have, while you have it. For hikers considering embarking on the long journey out East, Waite says to just go for it. “You don’t know what tomorrow holds,” Waite said. “There’s never a good time to go live in the woods for six months, so you might as well do it now.”

External is for sale at Chaucer’s Books and The Book Den. See externalhikingbook.com.

Walking with Leopard Sharks at Devereux Beach

A Mom Promises They’re Slow, Gentle, and Never Bite

Walking with Leopard Sharks at Devereux Beach

A Mom Promises They’re Slow, Gentle, and Never Bite

by Lisa Conti

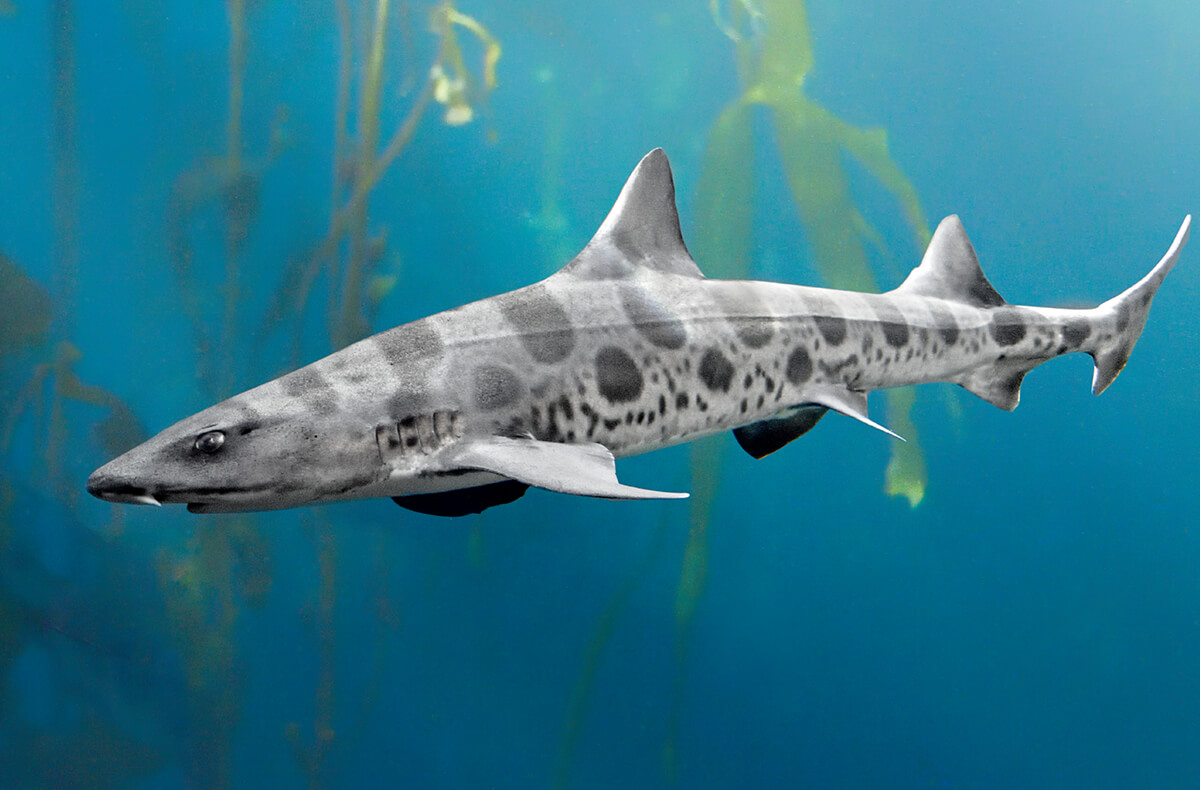

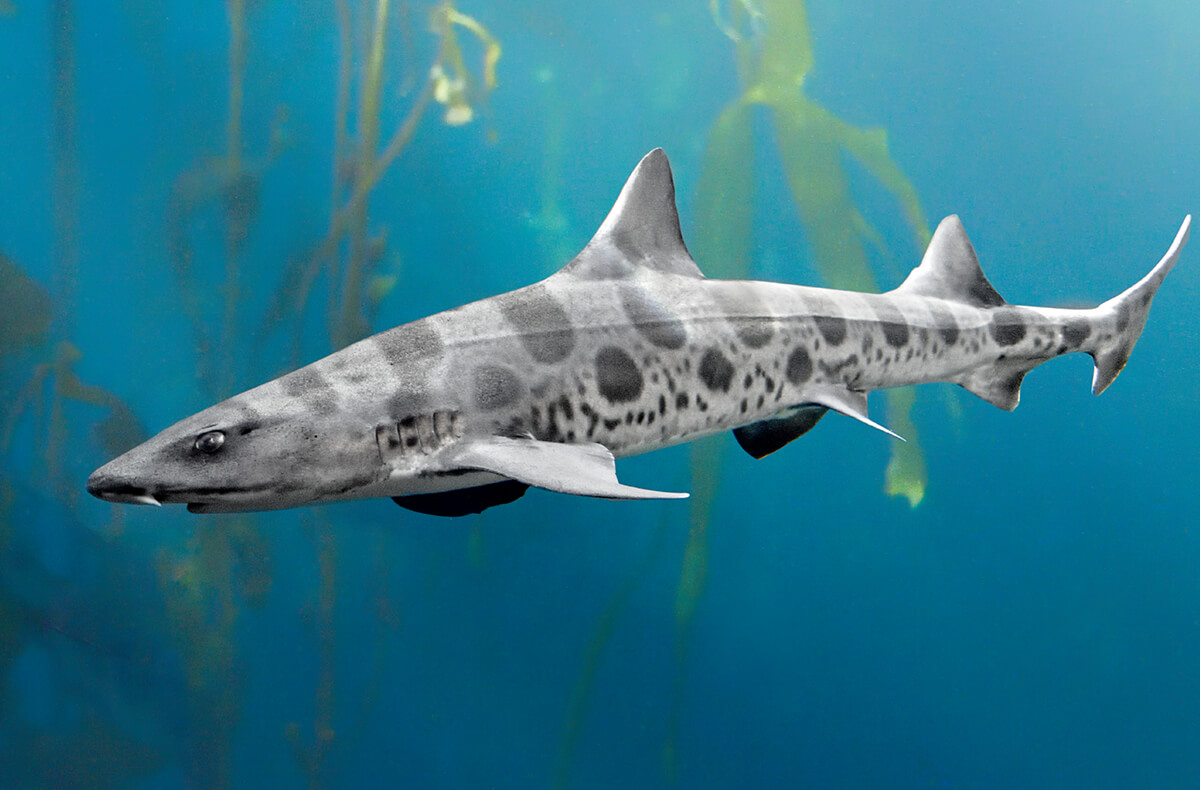

Leopard sharks are pretty much harmless to humans. | Credit: Courtesy

Shuffle,” I remind everyone, and the kids’ sloshing footsteps transition without dispute to quiet slides. Eight tiny sandstorms swirl. Feet-dragging is a precaution we take to startle off stingrays. Earlier, one had fluttered away from me like a kite trailing a streamer. But we’re not here at Devereux Beach in Isla Vista looking for frying-pan-shaped fish. We’re here to see the leopard sharks.

Before setting out, I knelt on the sand and with my most serious mom-voice briefed my two kids and their cousin about the adventure. I promised that the sharks are slow and gentle and never bite, but we mustn’t touch or disturb them. And don’t wade into their territory — let them come to us.

We know that our best bet at locating them is to wait until mid-tide. After some time on the beach, walking and watching, we spot a few dorsal fins. We enter the ocean cautiously. We all look down, silent, hands shielding our faces from the glare, eyes scanning. I lead them past their ankles, past their knees, until the children stand nearly waist deep.

But as we approach a group of sharks, we overstep, and one flicks its tail, dramatically darting towards the horizon. We freeze and watch. True to my word, the rest of the herd goes about their business, methodically gliding and circling through the shallows. Soon, they are swimming around our legs as if we’re just another clump of seagrass planted in the sand. I notice that the shark passing near the 9-year-old cousin is quite large, nearly four feet.

The shallows are relatively warm for these cartilaginous fish (in the mid-60s), and today, despite the smell of churned-up seaweed, the water is clear. We have fleeting, yet pristine views of dorsal fins cutting through the surface. And as the sharks swim into view, their spots for which they are named emerge as artful, dark markings.

I first heard about the sharks in April of 2018 from a friend who had taken her children tide-pooling. “They were just knee deep, and so many,” she marveled. “I think they’re breeding.” After a gestation period of 12 months, leopard sharks give birth to foot-long, teeth-bearing, live young. Between April and July, a female can birth more than 30 pups. Because we see only large sharks, it’s likely we’re seeing females who return to the warm shallows daily to incubate their eggs. I visit week after week through the summer and never fail to see a group.

The sharks navigate through murky water using more than just their vision. By detecting chemicals and electrical fields, they can smell out food concealed under sand and find their way through the open ocean. I find myself wondering what the sharks think of the neoprene eau de cologne that frequents this surf zone. On several occasions, I notice surfers walk through, each party seemingly unaware of the other. Yet when there’s a lot of activity, the sharks retreat.

We watch the sharks steadily undulate through the water. They feed with their mouths at ground level, searching the sand and rock bottom for shellfish, worms, and other hiding creatures. Using their mouth to suction their prey, they bite their catch, then swallow it whole.

Later, when the tide moves farther out, we walk on the dry seafloor and squat along the edge of the tide pools and search for crabs, octopus, and other could-be leopard-shark snacks. Finally, after we’re all shivering and hunger gets the better of us, we make our way back up the stairs to the blufftop, drive to Super Cucas, encircle a platter of super nachos, and share stories of walking with the sharks.

Staff Gear Reviews for 2019

These Three Items Make Life Outdoors a Little Easier

Staff Gear Reviews for 2019

These Three Items Make Life Outdoors a Little Easier

by Matt Kettmann , Chuck Graham, and Tyler Hayden

Gear Reviews | Credit: Courtesy

See campchef.com.

See atlaspacks.com.

Adventure for Hire 2019

Companies to Help You Enjoy the Great Outdoors

Adventure for Hire 2019

Companies to Help You Enjoy the Great Outdoors

A-FRAME SURF SHOP:

Retail surf shop offering lessons. 3785 Santa Claus Ln., Carpinteria; 684-8803; aframesurf.com.

BICI CENTRO:

Nonprofit community bike shop, education center, thrift store (secondhand bikes and parts), and repair help. 434 Olive St.; 617-3255; bicicentro.org.

BICYCLE BOB’S:

Bike shop including trek, service, and demo models, rides, and more. 320 S. Kellogg Ave., Goleta; 682-4699; bicyclebobs-sb.com.

CAL COAST ADVENTURES:

Bike/kayak/paddleboard rentals/tours, surf lessons. Bikes: 736 Carpinteria St.; Boards: West Beach by Stearns Wharf; 628-2444; CalCoastAdventures.com

CALICO HUNTER CHARTERS:

Fishing trips, specializing in sea bass. 484-2041; calicohuntercharters.com.

CAPTAIN JACK’S TOURS & EVENTS SANTA BARBARA:

With so many fun things to do here in Santa Barbara, Captain Jack’s Tours & Events has something for everyone. 564-1819; captainjackstours.com.

CHANNEL ISLANDS ADVENTURE COMPANY:

Guided Channel Islands and Santa Barbara kayaking, surf lessons, stand-up paddleboarding, wine tours, and more. 884-9283; islandkayaking.com.

CHANNEL ISLANDS AVIATION:

Fly to the islands, refuel, or learn to pilot planes. Camarillo Airport, 305 Durley Ave., Camarillo; 987-1301; flycia.com.

CIRCLE BAR B STABLES:

Renting horses for 81 years. 1800 Refugio Rd., Goleta; 968-3901; circlebarb.com.

CLOUD CLIMBERS JEEP TOURS:

Wine, adventure, and more in Santa Barbara and Ojai. 646-3200; ccjeeps.com.

CLOUD 9 GLIDER RIDES:

Bird’s-eye views from ultralight gliders. Santa Ynez Airport, 900 Airport Rd., Santa Ynez; 602-6620; cloud9gliderrides.com.

CONDOR EXPRESS:

Whale watching and more. 301 W. Cabrillo Blvd.; 882-0088; condorexpress.com.

E-BIKERY:

Opening mid-summer for electric bike rental/sales/tours/accessories. 506 State St., 869-2574; e-bikery.com.EL CAPITAN CANYON RESORT:

Coastal nature lodging. 11560 Calle Real, Gaviota coast; (866) 352-2729; elcapitancanyon.com.

EAGLE PARAGLIDING:

Paragliding lessons, pilot training, and tours by a team of instructors led by Rob Sporrer. 968-0980; eagleparagliding.com.

FASTRACK BICYCLES:

Bike shop. 118 W. Canon Perdido St.; 884-0210; fastrackbicycles.com.

FLY AWAY HANG GLIDING:

Lessons, new and used equipment. (802) 558-6350; flyawayhanggliding.com.

HAZARD’S CYCLESPORT:

Bike shop. 110 Anacapa St.; 966-3787; hazardscyclesport.com.

ISLAND PACKERS:

Transportation to Channel Islands, whale watching, and harbor cruises. 1691 Spinnaker Dr., Ste. 105B, Ventura; 642-1393; islandpackers.com.

ISLA VISTA BICYCLE BOUTIQUE:

Bike shop serving the Isla Vista community for more than 30 years. 880 Embarcadero del Mar, Isla Vista; 968-FEET (3338); islavistabicycles.net.

J7 SURFBOARDS:

Surf shop. 24 E. Mason St.; 290-4129; j7surfdesigns.com.

KA NAI’A OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB:

Competitive and noncompetitive canoeing and lessons. 969-5595; kanaia.com.

MOUNTAIN AIR SPORTS:

Skis, snowboards, camping equipment, kayaks, footwear, trail running, specialty, and more. 14 State St.; 962-0049; mountainairsports.com.

MULLER AQUATIC CENTER:

Aquatic physical therapy, open swim, and aquatic fitness classes. 22 Anacapa St.; 845-1231; mulwebpt.com.

OPEN AIR BICYCLES:

Sales, rentals, repairs, and safety checks. 1303 State St.; 962-7000; openairbicycles.com.

PADDLE SPORTS CENTER:

Stand-up paddleboard and kayak rentals. 117 Harbor Wy., Ste. B, and 5986 Sandspit Rd., Goleta; 617-3425; channelislandso.com.

PLAY IT AGAIN SPORTS:

Secondhand and new gear. 4850 Hollister Ave., Ste. B; 967-9889; playitagainsports.com.

REI:

Gear, rentals, repairs, classes, and organized outings. 321 Anacapa St.; 560-1938; rei.com/stores/134.

S.B. ADVENTURE COMPANY:

Channel Islands exploration, kayaking, biking, climbing, surfing, team building, and more. 32 E. Haley St.; 884-WAVE (9283); sbadventureco.com.

S.B. AQUATICS:

Scuba shop offering lessons, equipment, rentals, classes, scuba certification, and more. 5822 Hollister Ave., Goleta; 967-4456; santabarbaraaquatics.com.

S.B. BICYCLE COALITION:

Advocacy and resources for bike safety, access, and education. 845-8955; sbbike.org.

S.B. ROCK GYM:

Indoor gym, outdoor tours, classes, and youth programs. 322 State St.; 770-3225; sbrockgym.com.

S.B. SAILING CENTER:

Coastal and Channel Island cruises, a sailing club, rentals, lessons, kayaking, stand-up paddleboarding, and more. 302 W. Cabrillo Blvd.; 962-2826; sbsail.com.

S.B. SEA CHARTERS:

Fishing, charters, tours, filming, photography, and transportation. 896-0541; sbseacharters.com.

S.B. SWIM CLUB:

Make swimming a daily routine. Youth and adult programs offered. 401 Shoreline Dr.; 966-9757; sbswim.org.

S.B. WINE COUNTRY CYCLING TOURS:

Pedal through the vines. 1693 Mission Dr., Solvang; (888) 667-8687; winecountrycycling.com

SEA LANDING:

Jet-ski and kayak rentals, fishing, charters, scuba, whale watching, and more. 301 W. Cabrillo Blvd.; 963-3564; sealanding.net.

SEGWAY OF S.B.:

Multiple tours, Segway and SoloCraft sales, Polaris Slingshot rentals. 122 Gray Ave.; 963-7672; segwayofsb.com.

STAND UP PADDLE SPORTS:

Lessons, rentals, and retail. 121 Santa Barbara St.; 962-SUPS (7877); paddlesurfing.com.

SUNSET KIDD:

Sails, whale watching, charters, cruises, and more. 125 Harbor Wy., Ste. 13; charters: 962-8222, yachts: 965-1675; sunsetkidd.com.

SURF HAPPENS:

Surf lessons and camps for all ages; retail shop in Carpinteria. 13 E. Haley St. and 3825 Santa Claus Ln., Carpinteria; 966-3613; surfhappens.com.

SURF N’ WEAR BEACH HOUSE:

Retail surf shop offering lessons. 10 State St.; 963-1281; surfnwear.com.

TRUTH AQUATICS:

Fleet of boats for diving, fishing, and oceanic trips. 301 W. Cabrillo Blvd.; 962-1127; truthaquatics.net.

VELO PRO CYCLERY:

Rentals, sales, and repair. 15 Hitchcock Wy. and 5887 Hollister Ave., Goleta; 963-7775 and 964-8355; www.velopro.com.

WAVEWALKER CHARTERS:

Fishing and whale watching. S.B. Harbor, Marina 3; 895-3273; wavewalker.com.

WHEEL FUN RENTALS:

Skates, bikes (specialty and otherwise), boogie boards, and more; 24 E. Mason St.; Hilton S.B. Beachfront Resort, 633 E. Cabrillo Blvd.; Hyatt Centric S.B., 1111 E. Cabrillo Blvd.; 966-2282; wheelfunrentalssb.com.