Santa Barbara’s Notes for Notes Conquers America

Music Program Succeeds at Bringing Confidence and Skills to Young People

by Michelle Drown | Published September 19, 2019

Inside the Boys & Girls Club on Canon Perdido is a space that feels like a sanctuary — a musical sanctuary. It’s the first of the studios created by Notes for Notes (N4N), a now widely renowned national music program for young people that started right here in Santa Barbara.

“The space sets the tone,” said Rod Hare, one of the three founders of N4N. “Your music is taken seriously; your freedom of expression is taken seriously. You are treated as a musician. … So whatever’s going on in your life out there, in here, you’re a musician.”

The three rooms are set up as a small recording studio. In the gigging area, teens can experiment on myriad instruments — guitars, drums, keyboards. In the engineering room, there is a multitrack mixing board, where they produce the songs they’ve recorded in the sound booth.

The program, launched in 2007, began as a dream of Phil Gilley, who from a young age believed music was a vital means of human expression. This notion really hit home when, in his early twenties, he moved to Santa Barbara and began volunteering as a Big Brother. Gilley was looking for a way to connect with his young charge and immediately thought about teaching him guitar. The boy, not surprisingly for a youth, wanted to play the drums instead. But Gilley didn’t own a drum set or have access to one, nor could he afford lessons. So the two of them would hang out at Instrumental Music on upper State, banging on the store’s demonstration drum kit. Why, Gilley wondered, wasn’t there a space where kids could create music and not have to pay for lessons or buy instruments? This idea would soon come to fruition in a series of providential coincidences, but the seed for the dream was planted years ago.

Lightning in a Bottle

When Phil Gilley was growing up in Vermont, he wanted to play an instrument but struggled to learn how to read sheet music. His 3rd-grade teacher, Ms. Brown, told him, “If you can’t read, you can’t play.” So Gilley gave up until high school, when his mother bought him a guitar and he discovered tablature, a simplified method that allowed him, for the first time, to begin to play music.

The confidence he gained from learning the guitar stayed with Gilley. Eventually, he became convinced that creating music was the way to reach young people who, for whatever reasons, felt marginalized and unheard. At first, he thought about building a mobile music studio that could go to different schools, offering youth a place to play with instruments. But that would take money, and at the time he was working as a valet at Lucky’s restaurant in Montecito.

The Lucky’s job turned out to be fortuitous, because at the same time, Natalie Noone was working there as a

waitress. Raised in Santa Barbara, Noone, the only child of English singer/songwriter Peter Noone and his wife, Mireille Noone, was captivated by Phil’s vision. “Late at night when we were closing up shop, Phil said to me, ‘Hey, you’re a musician. Your dad’s a musician. I have this idea,’” Noone recalled.

Gilley told Noone that he believed music opened doorways to communication and explained how it allowed him to bond with his Little Brother. When he started describing the mobile music studio scheme, “it revealed this need that I completely connected with,” said Noone. “We realized if you have a youth that wants to play an instrument and those instruments have been taken out of public schools and even some private schools … it would be really difficult to have a casual initial encounter with an instrument without having to pay for studio time or lessons.”

Noone was all in, and they began the process of getting nonprofit status and naming the project Notes for Notes. Quickly the idea morphed into creating a stationary studio when they learned about a new teen center the City of Santa Barbara was opening in the building on the corner of Victoria and Chapala streets. Noone and Gilley were given 150 square feet to set up a place where teens could make music. “It was basically just all the instruments we could get our hands on — stuff from my house and whatever we could find,” Noone explained. “Natalie actually got one of the first donations so we could buy a little electronic drum kit,” said Gilley. “So we had a guitar, a keyboard, and a drum set in there.”

“The whole basis of the organization was that these youth need a place to go without ‘no’ being the first thing they hear when they walk through the door,” said Noone, “because that allows us to have a conversation with them.”

From the beginning, Noone and Gilley decided that censorship was not an option. They wanted to offer a place where teens could play anything — rock and roll, hip-hop, whatever — a no-rules kind of organization in which self-expression was the main purpose. “One of our core pillars is to help youth build confidence,” said Gilley.

A few months in, Gilley met another person who would help move Notes for Notes forward.

A Meeting of Minds

Rod Hare, a businessman who was born and raised in Santa Barbara, had also been a Big Brother and had long thought that music could be the bridge that would help the young people he had met in that program.

In 2006, Hare told Paul Dore, the Santa Barbara Bowl’s board president, about his idea to create a Big Brother/Big Sister–like program but with music at the center. Dore liked the idea and suggested Hare join the Bowl’s then–newly formed Education Outreach Committee. This turned out to be key in making Notes for Notes a reality.

A year later, in 2007, when Hare was visiting the teen center to check out another project for the Bowl, he noticed a little drum kit, a Mac, and a guitar hanging on the wall. “What’s this?” he wondered, and Gilley, who by now was overseeing Notes for Notes during the day and parking cars at night, told Hare about his experience as a Big Brother and how Notes for Notes had come into being. “Rod was like, ‘Holy cow.’” This was essentially the idea Hare also had, Gilley recalled.

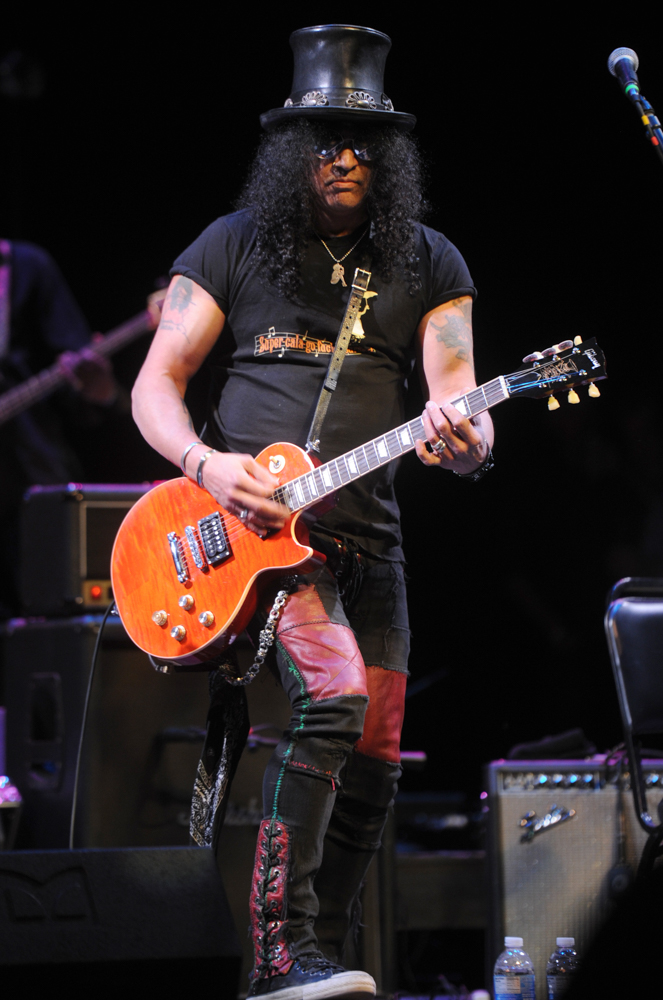

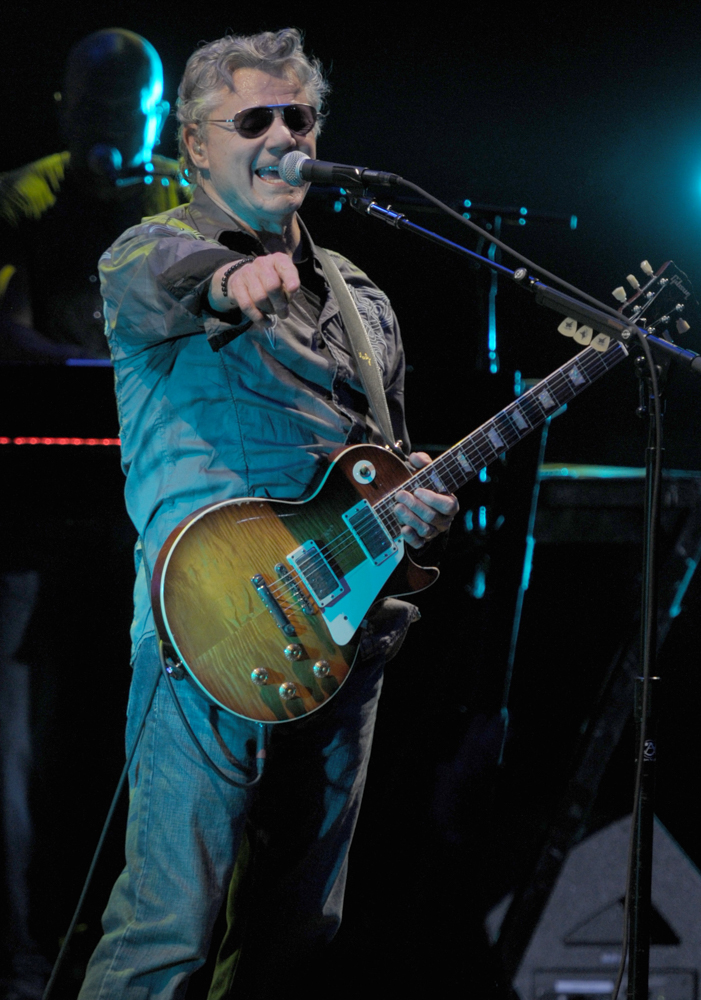

Seymour Duncan, Alastair Greene

Slash

Steve Miller

“Looking back on meeting Phil, I don’t want to overstate it, but it was like two rivers converging,” Hare said. He invited Gilley to lunch and told him about his similar idea, but one that could grow beyond Santa Barbara to any city in the country. All they had to do was team up with a national organization, ideally the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

Hare joked that nobody ever wanted to be the guy who proposes marriage on the first date. But “I was basically in love immediately,” Hare recalled. “And so I said to him, ‘Would you be willing to make this your life’s work? Because I actually think that we can raise the money.’” Gilley was on board right away. “In hindsight, it was just absurdly audacious,” Hare said. “This was literally the second time we’d met.”

Hare took the proposal to the Bowl committee, which put up $18,000 inseed money. Until that point, Gilley had essentially funded Notes for Notes on a credit card. The influx of Bowl funds allowed Gilley to spend more time at the studio and to cut some hours from his Lucky’s job.

Another great help were Noone’s deep ties to Santa Barbara’s music scene. She spearheaded a benefit concert at SOhO, in which she convinced her dad, Peter Noone, Herman’s Hermits’ former frontman, to perform. He in turn got Jeff Bridges, who had just played a singer/songwriter in the film Crazy Heart, to join him onstage.

Natalie Noone has never forgotten these early advocates — Bridges, Martin Gore from Depeche Mode, the Santa Barbara Bowl, and others — whose contributions were critical to the program’s early success. “They really stuck their necks out for us in the beginning, sort of legitimized us and made people pay half a second of attention to us.”

Things moved quickly then for N4N. At the end of 2007, Hare, Gilley, and Noone were introduced to Carolyn Brown, who was running the Boys & Girls Club at that time. “‘I’ve got this room here, and we’re not doing anything with it,’” Hare recalled her saying. They accepted the offer and tried to make the space look as cool as possible.

By the end of ’08, the Eastside studio was up and running and had even had its first celebrity guest musician, multiplatinum recording artist Robin Thicke. Inviting up-and-coming and established artists — such as Jack Johnson, Glen Phillips, Steve Miller, and Alan Parsons, to name just a few — to visit Notes for Notes’ studios and interact with the youth is a practice the program continues to this day.

Gilley believes that every donation — time or money — is what he describes as “creating more notes for youth.” It also becomes a gift to the people of the music community, who are using their “notes” to help the next generation of musicians make their own “notes.” The more artists who have gotten involved have raised the Notes for Notes profile and allowed them to build relationships that help the organization to grow.

One of their biggest challenges in the early days was how to handle the gang divisions plaguing Santa Barbara at the time. Kids who lived on the Westside didn’t feel safe going to the Eastside studio. Although N4N still had the small space in the West Victoria Street teen center, it did not offer a well-equipped studio like the one across town. Gilley and the team realized they needed to find the money to open a similar high-quality studio at the Westside Boys & Girls Club. It took a number of years, but in spring 2011, the new studio was opened.

Notes for Notes’ marriage with the Boys & Girls Club would prove to be a match made in heaven. In addition to giving the fledgling nonprofit a permanent space, the Boys & Girls Club program provided an already existing structured environment that young people respected. The association has also allowed N4N to expand its reach over the last 12 years to other cities, including New York City, Detroit, Los Angeles, Austin, Denver, St. Paul, New Orleans, Memphis, Nashville, Atlanta, Cleveland, Washington D.C., Chicago, and San Francisco.

Tennessee Days

Nashville was the first place N4N opened a studio outside of Santa Barbara. Noone, who moved there for college, was already plugged in to the Nashville music scene, so Gilley and Hare flew there “to plant their flag.”

Things really took off when they met with Hot Topic, the Los Angeles–based clothing store specializing in rock-and-roll T-shirts. “I call them our godfather,” said Gilley. The company had an outreach foundation that gave N4N a grant to build the Westside Santa Barbara studio, and it later contributed $75,000 to open two studios in Nashville.

In the country-and-western music capital, N4N forged important relationships with Gibson Brands and, eventually, the Country Music Association, both of which continue to be major backers of the program. Gibson now supplies guitars for all the N4N studios, and CMA has already funded 13 N4N studios in cities across the United States. Today, Gilley considers Nashville the unofficial hub of Notes for Notes.

Smart Moves

Twelve years in and N4N has not just lasted, it is thriving. Why? “I think we are on the cutting edge of something very exciting,” Gilley said. A recent study published by the Journal of Community Psychology seems to support his belief. UCSB PhD candidate Joshua Sheltzer interviewed N4N staff and alums and found that the continued exposure to music in the studio setting helped young people develop critical social and performance skills, and perhaps more important, a greater sense of self-confidence and identity.

For Gilley, the study was a wonderful endorsement of the work he and his colleagues have been doing for the past decade. To have an analysis from an independent party, conducted over a number of years, that Gilley felt got to the core of their mission, was a level of scientific validation the program had never had before. “It’s inspiring,” he said. “It really taps into the mental health of children. Yes, it’s music education. Yes, it’s access to instruments and all these tools. But most important, it’s using music as a way to connect with other people.”

The study also offers a chance to quantitatively demonstrate success to corporations and foundations, groups that N4N needs to financially sustain its national programs. “Assigning scientific numbers and data to emotional growth through the arts is very challenging,” said Gilley. “Hopefully this report helps people open their eyes to a different way of measuring success other than just graduation rates and grades.”

Home Is Where the Heart Is

In Santa Barbara, Notes for Notes continues to be hugely successful, with thousands of kids using the program every year. Recently, Kenny Loggins, through his work with the Good Tidings Foundation, was able to fund much-needed renovations for the two Santa Barbara studios, which had not been updated for nearly a decade. The facelift included new instruments and equipment, which brought them up to the same level as the more recent studios built in other cities.

Though the original three founders all now live elsewhere — Noone and Hare split their time between Nashville and Santa Barbara, and Gilley is based out of Detroit — the Santa Barbara staff has embraced the organization’s mission: Kris Ehrman is the metro manager, David Rojas runs the Eastside, and Alex Perez heads up the Westside.

“[N4N] really taps into the mental health of children. … [I]t’s using music as a way to connect with other people.”

— Phil Gilley

Ehrman, who has worked at N4N for more than eight years, is a musician himself. By reaching out to other groups in the area such as the Blues Society, he has been able to connect Notes for Notes with Santa Barbara’s greater musical community, one of the core principles of the program.

On the Eastside, Rojas, who plays in the Rent Party Blues band with Ehrman, serves as its program director. He’s developed a project, World Music, that helps the kids learn about the origins of different genres. Through this, he has been able to bring into the studio to talk to the teens a number of professional musicians who have a wide range of styles.

Rojas and Ehrman also crafted a band of student musicians called the Jazz Villains. Gilley said it’s one of the best bands ever to come out of a Notes for Notes studio. On Tuesday, September 24, the Jazz Villains are opening for Steve Miller, who is playing a Notes for Notes benefit concert at the Lobero. The Jazz Villains have been together long enough that several members have rotated out. Some were accepted to Massachusetts’s Berklee College of Music, and one is at Santa Barbara City College and will join the Villains at the concert.

Introducing the young people at Notes for Notes to artists of all different levels is a critical part of the program, said Gilley. “It shows them what the payoff can be, and what the struggles can be, and what the struggles still are if you want to make it. It’s the wisdom they can pass down as artists.”

Today, Gilley is careful that, in all its successes and expansions, Notes for Notes does not lose its way. “I see my greatest responsibility as making sure the choices we are making today do not erode what is at the core of our organization,” he said. “I sometimes question how we find such talented people who want to volunteer and work in the studios. But I like to think that, in a small way, it’s because we know what a gift music is.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.