Paranoia and Power

What Previous Impeachments Can Teach Us About Today

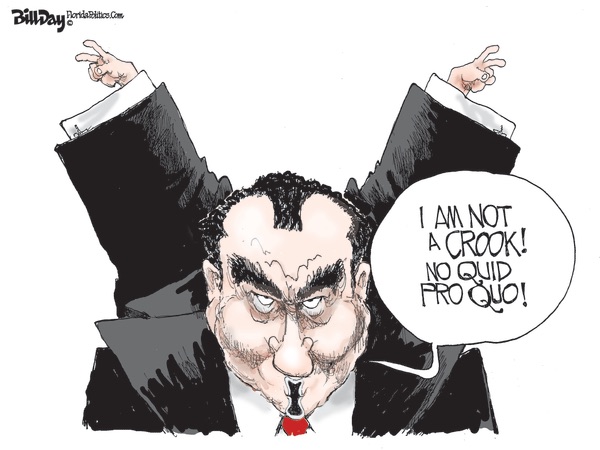

A president faces impeachment charges after he is accused of direct involvement in an unsavory scheme aimed at boosting his reelection. Against a tense background of controversy over an American military deployment, the chief executive fumes, even as one top aide after another gets implicated in the widening scandal.

The turbulent presidency of Donald Trump? Actually, it’s a description of the final months in office of Richard M. Nixon.

Impeaching a U.S. president is a rare occurrence, but not an unprecedented one: Three previous holders of that office have faced the real possibility of removal by a hostile Congress. Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton were both impeached by the House of Representatives, then acquitted by the Senate (barely, in Johnson’s case). Nixon resigned before the process could reach its conclusion.

“There’s an element of paranoia that comes with having power and trying to keep it,” said Alice O’Connor, a UC Santa Barbara historian of public policy who has studied Nixon’s presidency. “It was Nixon’s paranoia that led to the effort to get dirt on an opponent who obviously was not going to win the election.”

She sees parallels between that behavior and Trump’s reported insistence that Ukranian officials investigate a widely debunked conspiracy theory about the 2016 campaign. “They’re very different people psychologically,” she said, “but the way their paranoia becomes institutionalized is very similar.”

To get some historical perspective on the current impeachment process, I spoke with three UC Santa Barbara historians: O’Connor, Civil War-era expert Giuliana Perrone, and Nelson Lichtenstein, who is writing a book about Bill Clinton’s presidency.

As Perrone notes, the previous impeachment that most closely echoes Trump’s troubles is clearly the one that drove Nixon from office in 1974. Both of those cases involve abuse of power, whereas the Clinton scandal revolved around sex, while Johnson’s was driven by his intense policy differences with the Congress.

Johnson’s presidency was “a time of deep rupture and pain, when the nation is grappling with a huge loss of life,” Perrone noted. The Civil War was still fresh in everyone’s memory, and northerners were mourning the deaths of their loved ones. Many felt that, unless the war produced a better, more just nation, their sacrifice would have been meaningless.

Thus there was popular outrage when Johnson, a pro-slavery Tennessean who had been vice-president for only four months when Lincoln was assassinated, created an easy path for Southern reintegration to the union. The president and Congress spent months in an intense power struggle, as laws instituting rights for freed slaves were passed, vetoed, and overridden.

Finally, Congress passed what Perrone calls “a trap” for Johnson — the “Tenure of Office Act,” which essentially forbade him from firing the Cabinet members Lincoln had installed. His attempts to get around that ultimately led the House to impeach him in 1868. The Senate held a trial, but “Johnson’s lawyer passed along quiet assurances that if the Senate acquitted him, Johnson would stop interfering with Congress’ reconstruction policies,” Perrone said. In the end, he kept his job by one vote.

The nation again found itself highly polarized in 1998, when a Republican-dominated House of Representatives led by firebrand Speaker Newt Gingrich impeached Bill Clinton following revelations the president had an affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

“There were two charges,” Lichtenstein said. “One was that he perjured himself in front of a grand jury investigating the Lewinsky case. The other was obstruction of justice. He had coached Lewinsky and one of her friends to lie, and had given her certain gifts.”

Clinton supporters argued these offenses did not rise to the level of “high crimes and misdemeanors” called for in the impeachment clause of the Constitution. The Senate agreed: Only 45 Senators ultimately voted for the first count, while the second split the chamber 50-50 — well below the two-thirds vote necessary for removal.

The case against Nixon was very different in nature. Officials of his reelection campaign authorized a break-in to Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in an attempt to get dirt on the opposition party. Nixon and his chief aides later facilitated “hush money” payments in an attempt to keep incident from the public.

“The actual charges are very similar to what is being contemplated in the investigation of Trump,” said O’Connor, pointing to abuse of power, obstruction of justice, and contempt of Congress. “There were layers of corruption surrounding the presidency during the Nixon administration, and they are even more overt in the Trump administration.”

That said, she sees major differences between the two eras, such as “the role of social media today, and Trump’s very effective use of it, at least so far.” Twitter gives Trump a way to keep his supporters engaged and in line that Nixon never had.

In addition, she argues the Trump administration has more “people in positions of power and responsibility who will do his bidding,” even when his orders are ethically and/or legally questionable. In contrast, Nixon’s attorney general Elliot Richardson, and his second in command William Ruckelshaus, resigned in the famous Saturday Night Massacre rather than agreeing to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox, who was investigating the president.

The most likely outcome for Trump at this point is impeachment by the Democrat-controlled House and acquittal by the Republican-controlled Senate. Some Democrats fear he will spin that into a “win,” but Lichtenstein notes that Clinton’s impeachment produced long-term damage for his party in two ways.

First, when Clinton’s vice-president, Al Gore, ran for president in 2000, “he viewed Clinton as toxic,” Lichtenstein said. “Clinton was sidelined during the campaign — although he was a very good campaigner who was very popular. A few trips to Florida might have made a difference.”

Second, “Clinton had enormous debts as a result of this. He wasn’t a rich guy, and he had huge legal bills. So he went on the speech circuit, getting hundreds of thousands of dollars from companies like Goldman Sachs. That began a process which tarnished both Clintons, making the public see them as too close to Wall Street.”

That reputation clearly contributed to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss. So in an indirect way, the Clinton impeachment may have given the nation President Donald Trump.