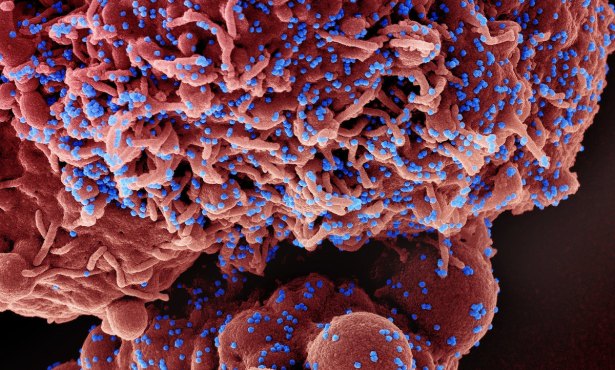

Santa Barbara Doctors Reject Using Unproven Drugs Against COVID-19

Hydroxychloroquine Can Have Serious Side Effects Despite White House Promotion

Santa Barbarans have succeeded in helping to flatten the curve. Staying home and following safety procedures are so far working to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Hospitals are not overwhelmed with patients dying of respiratory and organ failure. The number of people who are infected is trending at a pace best illustrated by a steady line upward on the charts rather than a spikey curve that soars into the stratosphere.

But for the 15 patients currently in the county’s hospitals’ intensive care units and their families, the vital question is how can the sick recover? Is there a drug that can cure?

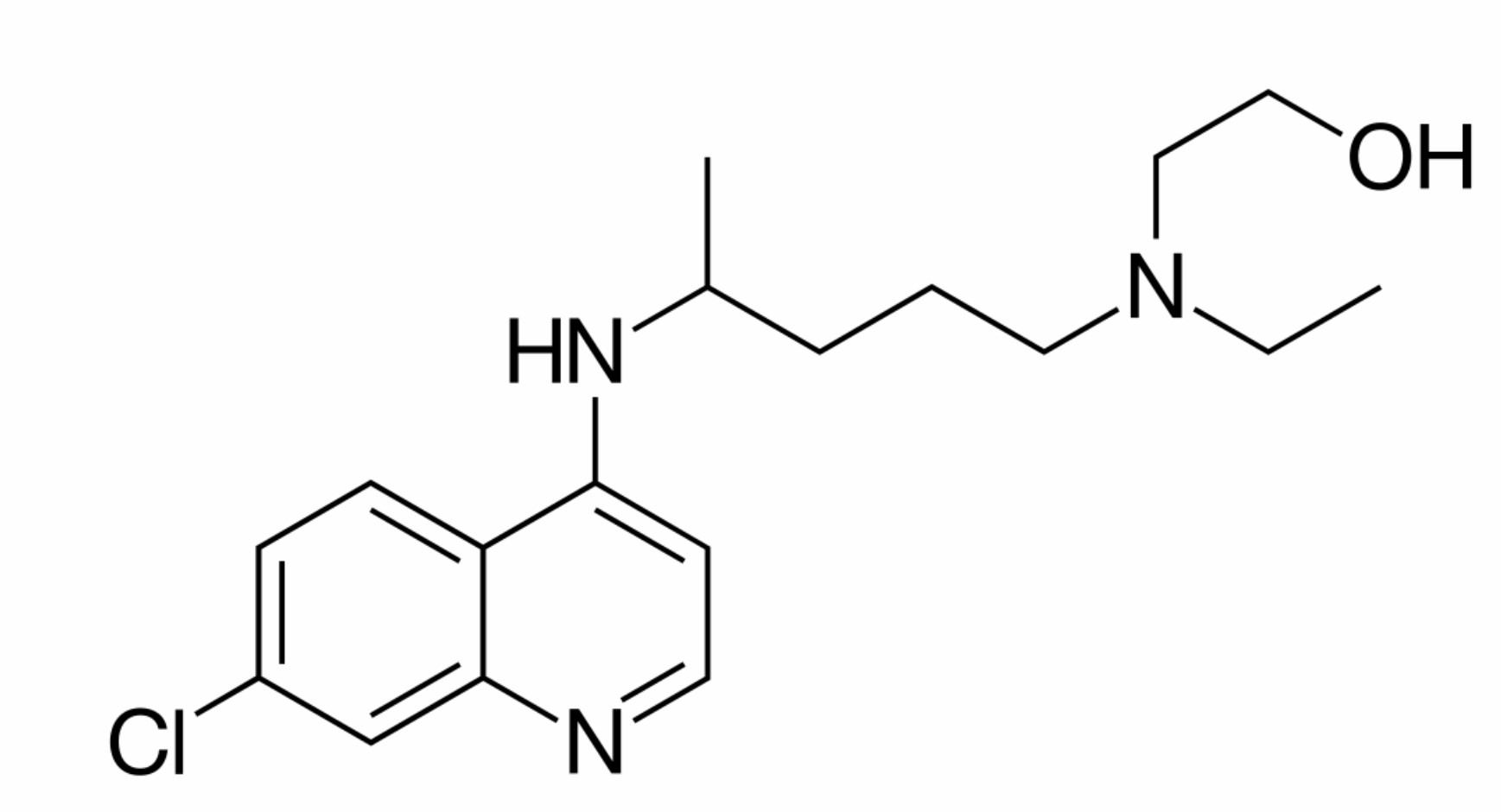

Among the drugs being discussed is hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). Generally prescribed to alleviate the painful symptoms of lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, it requires annual monitoring and can cause dangerous side effects including damage to the retina. If used for COVID-19, it can cause, in the short term, heart arrhythmia, seizures, and death.

But anecdotal stories about positive test results, including comments from the White House, suggest the drug would be able to keep the COVID-19 virus from replicating and prevent a patient’s immune system from exploding, which is how pneumonia and lung complications develop. “What do we have to lose?” President Donald Trump asked recently.

However, a recent study by French doctors found numerous problems with the touted test results, including the fact that patients who developed heart issues were dropped from the test, and the sample size of patients was too small to be conclusive. Another test in Brazil was stopped after large doses of chloroquine caused arrhythmia.

Many doctors in this country have publically worried about prescribing an untested drug, and pharmacists express downright annoyance that anyone would prescribe a drug in short supply simply in the hope that it might alleviate disease. Other medical professionals have pointed out that patients taking hydroxychloroquine for one ailment have also developed COVID-19.

Dr. Mark Bookspan, director of internal medicine education for Cottage Hospital’s residency program, expressed his concerns: “Treatments for any condition must take into account the risk of the treatment versus the benefits to be gained by the treatment,” he said. “The correct way to assess both the adverse effects of a potential therapy and its possible efficacy as a therapy is to undertake a prospective randomized double-blind-control study.” That would be a study in which neither the participants nor the experimenters know who is receiving what treatment, a procedure that prevents bias and diminishes the placebo effect.

Infectious disease specialist Dr. Lynn Fitzgibbons agreed, stressing the importance of clinical trials in determining if hydroxychloroquine was an effective treatment. “Because this is a new virus, clinical guidance on effective treatment protocols will take time — it will develop based on evidence gathered in data collected from trials,” she said.

In an effort to relieve the suffering of terminal patients, some hospitals are, nonetheless, cautiously allowing the use of drugs that aren’t fully proven. And important clinical trials have begun on a number of cures that might actually work — the anti-Ebola drug Remdesivir in several U.S. hospitals, the antiviral favipiravir in Japan, and immunosuppressants such as Tocilizumab and Sarilumab globally. At the National Institutes of Health, a randomized and blinded hydroxychloroquine study that includes a placebo is scheduled to finish in July 2021.

At the Santa Barbara Independent, our staff continues to cover every aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Support the important work we do by making a