Of Covid-19, Travel, and Family

Last Month Was a Lifetime Ago

The village seems dead, the roads empty. My mother, the village’s oldest resident, white-haired, clear-eyed, stares through the living room window; a ghost-like figure framed by the window’s white vinyl trim. We’d said an awkward goodbye, ten feet apart, at the front door. I have a cold so no hugs, just a blown kiss. I take a last glance toward her then steer the rental car out of the driveway and head for Heathrow. I don’t know if I’ll see her again. We’ve played this game so many times — fifty years of coming and going doesn’t get any easier. But, in true British fashion, we’ve both learned to hold back the tears at least until out of sight. Now a pandemic is running rampant through the country and the feelings of potential loss are magnified. Her carers inform her they won’t be able to care for her for a while. Government orders. I’m so glad my brothers didn’t follow me to California and live nearby.

My wife and I, plus two children and partners, had flown to the U.K. from Santa Barbara on March 5, the day the U.K.’s first death from Covid-19 was announced. The reason for the trip — my mother’s one hundredth birthday. She’d greeted us with an elbow bump and a wry smile. Covid-19, still something of a novelty then. The Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, boasted of shaking hands with virus contaminated patients at a hospital. (A month on, his action was seen as a reckless show of bravado as he fought for his life in a National Health Service ICU.)

At the Hertz depot at Heathrow car upon car line the lot. No rentals going out; a few stragglers coming in. The Hertz transfer bus, empty, except for my wife, me and our luggage. My daughter and daughter-in-law, nurses with essential jobs, had flown back to California a few days earlier avoiding the confusion of the lockdowns.

Terminal 5 is almost empty. A cheerful British Airways staff member relieves us of the hassle of negotiating the confusing auto-check in machines. There are no lines for security. No lines for anything. The departure areas, scattered with mostly Americans awaiting flights home, hoping those flights would not be canceled like our Air New Zealand flight (scheduled for the end of the week). We received no email, no phone call, no text from the airline offering an apology or offering to reschedule an earlier flight. Luckily, my brother had spotted a paragraph on the airline’s website stating flights to LAX from London would cease on March 21. Our flight was scheduled for March 22. We scrambled to get two seats on a British Airways flight for March 18, two days after the U.S. locked down its borders.

We await notification of our departure gate in the forecourt of a Starbucks while supping on lukewarm coffee for a price that some restaurants might charge for a three-course meal. I think about my mother. She’d not seem worried at the prospect of self isolation for weeks, perhaps months. She’d survived a lot over her one hundred years. She might be more equipped to handle this dramatic change in our lives than we are. After all she’s lived through the Great Depression, the Second World War, the swinging sixties, the 1987 hurricane, the death of a husband, the death of her youngest brother and most of her friends. She can live on nothing. What we in America consume in a week, she makes last a month. Although she gave up driving a year ago, she still manages to grow her own fruit and vegetables, freezing what she doesn’t eat for the winter months. She still makes jams, marmalades and chutney, of which in happier times I regularly smuggled back to California to stock up our larder, until the fallout from another cataclysmic event — 9/11, ended all that.

Would passengers for British Airways flight 281 to Los Angeles please proceed to gate 251.

We take a long hike and a shuttle to the gate where we sit silently thinking ahead to what might await us in California. Newspaper stories of thousands of people clustered chaotically together for hours awaiting health checks at U.S. airports leave an air of foreboding. I’d been afflicted with a hacking cough for days, suppressed now (and I hoped for the length of the flight) by a dose of Benalyn Chesty Cough.

The U.K. and U.S. governments are asking citizens to stay home and wash their hands. I think again of my mother. In the Second World War, she’d sacrificed a lot more than staying home and washing her hands. She lost her youngest brother and my father lost both his brothers. She was nineteen when it started. People in the village were frightened. They knew they were on the front line for a German invasion. When she witnessed a German plane being shot down by Spitfires in nearby fields, and bombs falling on neighboring farms, my mother knew she couldn’t sit at home and wait. So she left her sheltered life on the farm and headed to London to join the Female Army Nursing Yeomanry. Through the Blitz — fifty-seven nights of unrelenting bombing — she drove an ambulance and taught younger nurses to drive ambulances in the blackouts with no headlights. She learned vehicle maintenance, first aid, map reading, how to identify poisonous gases from their smell… and how to march. She learned to fire a series of weapons including a Tommy gun and a Colt revolver, once scoring a direct hit on a tank with a spigot mortar. She practiced street fighting with the Scots Guards — a useful skill to have when bringing up three teenage boys!

Attention passengers for British Airways flight 281. We will be ready to start boarding in ten minutes.

My wife gives me a quizzical look as I laugh out loud at the memory of my mother standing in our garage fiddling with the air valve on the carburetor of my Lambretta scooter. When my brothers and I were teenagers, it was always her we went to for advice when we had trouble with our motorcycles or cars. Our father was useless in that department.

Attention passengers on British Airways flight 281 — we are ready to start boarding now. People with disabilities and special needs please come to the front.

We line up to board with an abstract fear of being contaminated by a hidden virus. There’s no social distancing on an eleven-hour flight. The plane is half full of mostly young American students heading home earlier than expected. The flight seems interminable. A mere sneeze is weighted with significance. A mass sigh of relief is heard as the plane touches down at LAX. Half an hour passes before a gate opens up in an airport chock full of aircraft going nowhere.

We are going to disembark the plane in groups of ten to allow health officials to take your temperatures and ask some questions.

A motley crew of masked and gloved police officers, nurses and young volunteers await us. At arms’ length they scan our foreheads, then ask the same questions already answered in a form we’d filled out on the plane:

“Have you traveled to any of these countries?” Iran and China top the list. The U.K. is strangely not on the list at all.

“No.”

“In the past two weeks have you experienced shortness of breath.”

“No.”

“A fever.”

“No.”

“A dry cough.”

“No,” I repeat while trying to suppress a wet cough.

Designated healthy, we walk toward Immigration and Customs. On the last re-entry I’d made into the U.S., an immigration official looked at the battered green card and its photo of my 1983 face before staring incredulously at my 2017 face.

“Don’t you think you should become a U.S. citizen? Why aren’t you an American?”

I wanted to say: “It’s none of your bloody business. I pay my taxes. No other country asks me such a question.” Instead I just shrug.

The officious official then fingered the worn edges of the card (which isn’t green by the way). “Y’all are supposed to get a new one when they start to fray. Next time I’m gonna send you upstairs for security to deal with.”

Now, approaching immigration for the first time as a newly minted U.S. Citizen, I’m fully prepared to exercise my right to freedom of speech with a few well-chosen words if confronted by the usual sarcasm. But, I feel miffed — a computer, not a human being, stands between me and the outside world. I feed my shiny new U.S. passport into the shiny new machine. The shiny new machine likes what it sees. We head to baggage claim, collect our bags and walk out to the fresher air of an L.A. devoid of traffic. The welcoming smiles of our son and daughter-in-law provide a happy welcome at the end of a long day.

Two weeks of self-quarantine pass slowly. At the end, the whole of the country is self-isolating and self-distancing.

It is now April 16 and the official death toll in the U.K. has risen to 13,000, while in the US — 31,000. Boris Johnson, out of hospital, recuperates in his country residence Chequers, and admits he owes his life to the medical staff of the National Health Service, a treasured organization that his party has been defunding in the name of austerity since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Somehow the banks got bailed for their sins and the health service paid the price.

With the pandemic spreading across the country, thirty-million Americans are uninsured, many more under-insured and those who have lost their jobs have likely lost their health insurance too, causing the pandemic to spread and affect more people than any other country in the world. Why on earth would you have system with your health insurance tied to your job? It makes no sense. In most western countries, everyone pays a little extra in taxes and the nation is covered whether working or not. It’s called a public service. A nation’s health ought to be its first line of defense. What’s the point if a country spends hundreds of billions a year on an over-bloated military when it can’t protect its citizens from a virus? What’s the use of an aircraft carrier when you can’t protect its crew?

Meanwhile, my daughter and daughter-in-law are serving selflessly on the front lines of the pandemic. My daughter-in-law at Lompoc Hospital, heavily impacted by prisoners from the prison; my daughter, a traveling nurse, at the Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. We tried to dissuade her: “Are you sure you want to do this? Why do you want to go and put yourself in harm’s way?”

“Because it’s the right thing to do. It’s what I’m trained for.”

It is indeed the right thing to do. We worry about lack of PPE and the conditions they both work under but we are proud of them. My daughter possesses more than a little of her 100-year-old grandmother’s spirit.

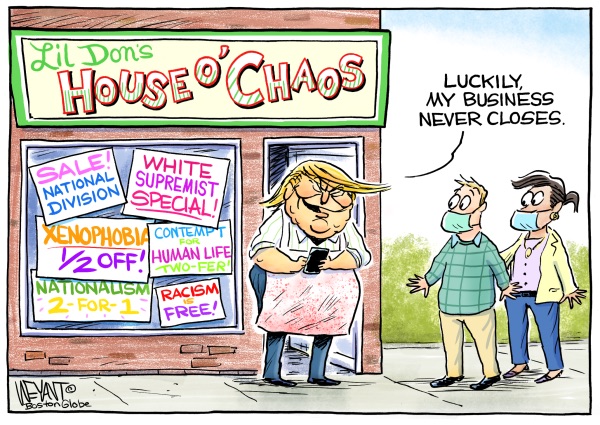

And while our nurses work their twelve-hour shifts on the front lines, I wash my hands and raise a middle finger to the Emperor (minus clothes) on TV spewing his daily lies. Some of the words previously reserved for the officious immigration official spring to mind:

“I pay my taxes and with that your salary, mate. Stop praising yourself, show some empathy … and do your bloody job!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.