Santa Barbara Commemorates Juneteenth

Voices from Our Vibrant Black Community

Published June 18, 2020

Over three thousand community members held space at the steps of the Santa Barbara County Courthouse on May 31, 2020. Community advocates Simone Ruskamp and Krystle Farmer Sieghart shared stories with the crowd of Blackness in Santa Barbara. They and other speakers shared on the atrocious murders of Black Americans like Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Meagan Hockaday, a Don who lost her life to an Oxnard Police Officer. “Elevate Black voices, lift up Black folks,” Ruskamp said. The list of countless names continued.

The Danzantes led us as we marched to the Santa Barbara Police Department. We laid our Black bodies in the intersection of Santa Barbara and Figueroa Streets for eight minutes and 46 seconds – the time a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck and ended his life. We asked non-Black people to kneel in solidarity. The silence overcame us, the sound of my siblings’ tears and heavy breath. There was a refusal by police and the Mayor to kneel in solidarity.

This is the story I remember; this is the story I will tell.

I am often asked, “Where are the Black people in Santa Barbara?” I am often called upon as the “diversity representative” as if any single voice can speak on behalf of all of our vibrant Black community. In this issue, we are pushing back on this erasure of the Black community and have collected stories from many black individuals, to present that vibrancy.

We invite you to share in our stories and our struggles, as our histories are American histories. We take both the inherited joy and inherited trauma that our Ancestors have shared with us and weave those into our own voice. Storytelling is rooted in Black heritage. We share our stories with our community, our real voices, to let you know we exist in this space.

So in response to the question posed earlier “Where are the Black people in Santa Barbara?” we borrow the words of speaker Courtney Frazier, who said, “Can you see us now?”

—Jordan Killebrew

Invisible in Plain Sight

Celebrating Juneteenth

Invisible in Plain Sight

Celebrating Juneteenth

by Sojourner Kincaid Rolle

“Jesse Thomas and Sojourner Kincaid Rolle | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss”

Juneteenth or National Freedom Day was officially recognized by the California Legislature in 2003 as a day of observance. The third Saturday in June was designated as time to honor and reflect on the significant roles that African Americans have played in the history of the United States. The history of Juneteenth goes back 156 years and commemorates the date June 19 in 1865 when the Union Army general Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, with the news that the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed two and a half years earlier on January 1, 1963. The Civil War was over and slavery was outlawed. The formerly enslaved people commenced celebrating their freedom from bondage with a huge feast.

There is a black community in Santa Barbara — with a long history of survival. It mirrors many black communities across America. Some families can trace their roots here back to the time of slavery. The NAACP chapter here was formed in 1919 following an incident involving Mr. Lewellen Spenser. The George Washington Carver Scholarship Club was started in 1931. There were identifiably black businesses on Haley Street — the Elk’s Lodge, the Golden Bird Restaurant, and Brother Brown’s Barber Shop.

In the early years, African American children attended Lincoln Elementary School on Cota Street, and following its closing, many went to Franklin Elementary School on the Eastside. Contrary to the widespread myth of being an “invisible community,” African Americans in Santa Barbara have always been in plain sight.

Black churches were central to the lives of many who lived here. The most prominent — St. Paul AME, Second Baptist, Friendship Missionary Baptist, Greater Hope Missionary Baptist, and Lewis Chapel CME — have been pillars in the community. Black clubs and civic organizations were mainstays in the social life, including the Eastern Star, the Masons, and the Elks, as well as the NAACP and the Carver Club.

Many of the African Americans who have been a part of the Santa Barbara community have family ties to Texas as well as the neighboring states Louisiana and Oklahoma. During the First Great Migration of the 1920s and 1930s, 1.5 million black families moved west, mostly to Los Angeles and San Francisco. And during the Second Great Migration (1940s to 1970s), over five million came west seeking to escape racism, segregation, and lack of economic opportunity.

Many of Santa Barbara’s black families were part of that 60-year migration. Well-known names in the history of our town, such as Simms, Thomas, Garrett, Moten, Hopkins, Seaton, Franklin, and Moore, came from towns in Texas including Midland, Bryan, Navasota, Tyler, Lamesa, Port Arthur, Jacksonville, and Mahair. Many who came here during the 1940s, now in their septuagenarian years, still remember their childhood days. They have strong memories of celebrating Juneteenth, even if they had not yet learned its significance. They remember the barbecues, drinking red pop, eating watermelon, and telling family stories. It was a day to celebrate and be free. For many, it was the only “black holiday” in the year.

It is through these families that the memories of Juneteenth celebrations and the stories of struggle and overcoming the harsh realities of racism have survived. It is a time of coming together, celebrating the old days, and teaching the children about their ancestors and the history of their families. In recent years, black family reunions — in Santa Barbara and nationwide — embrace the entire African American community.

During the past 50 years, all but three states have come to recognize and celebrate Juneteenth. The effort to make Juneteenth a federal holiday continues.

Sojourner Kincaid Rolle, a 35-year resident of Santa Barbara, is a poet, playwright and cultural activist. She served a two-year term as S.B.’s Poet Laureate (2015-2017) and is known for her work with young people and toward raising awareness throughout.

Santa Barbara Celebrates Juneteenth

Holding a Virtual Festival of Black History and Future

Juneteenth Is My Independence Day

Celebrating Our Ancestors With a Virtual Festival

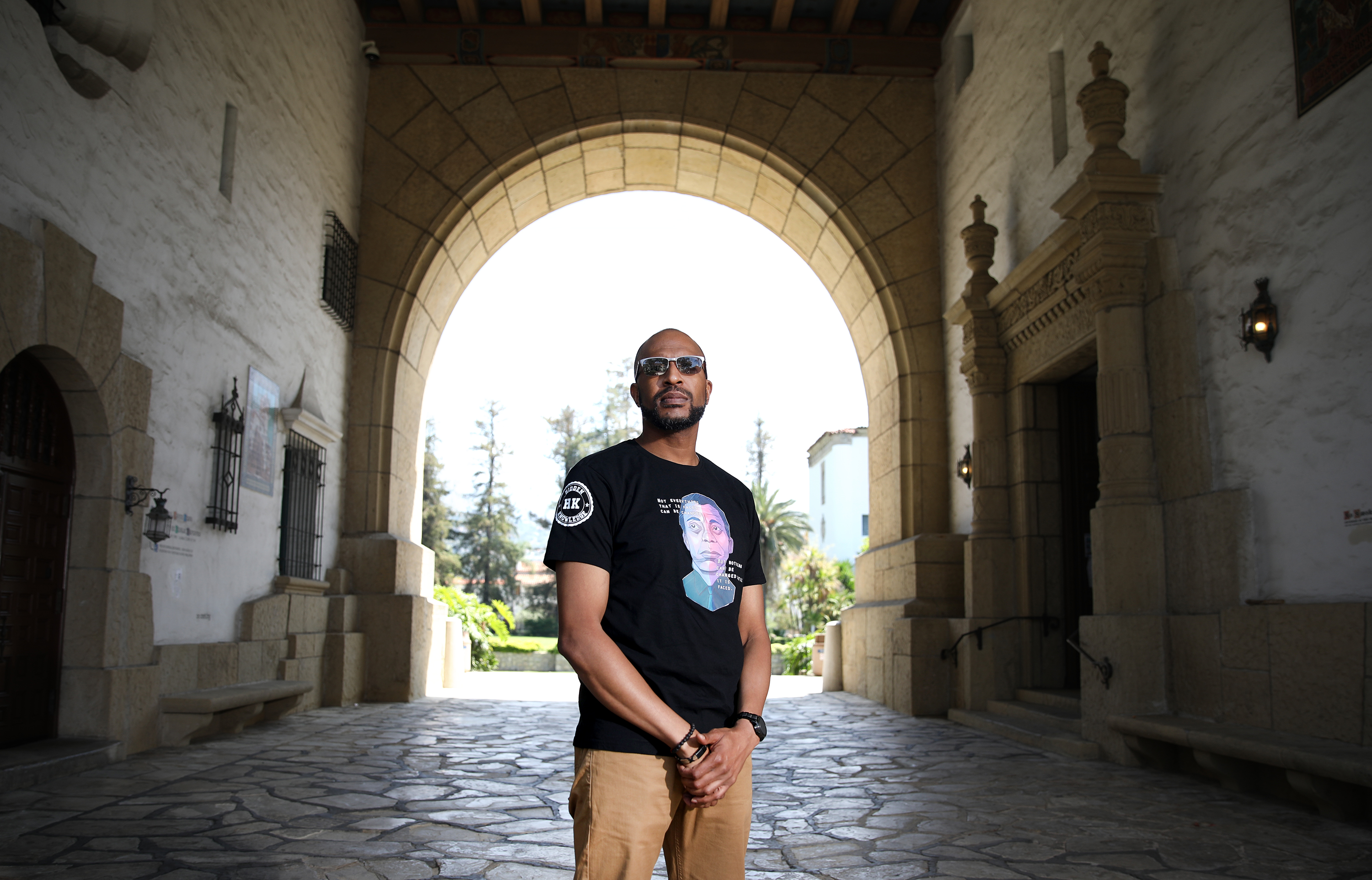

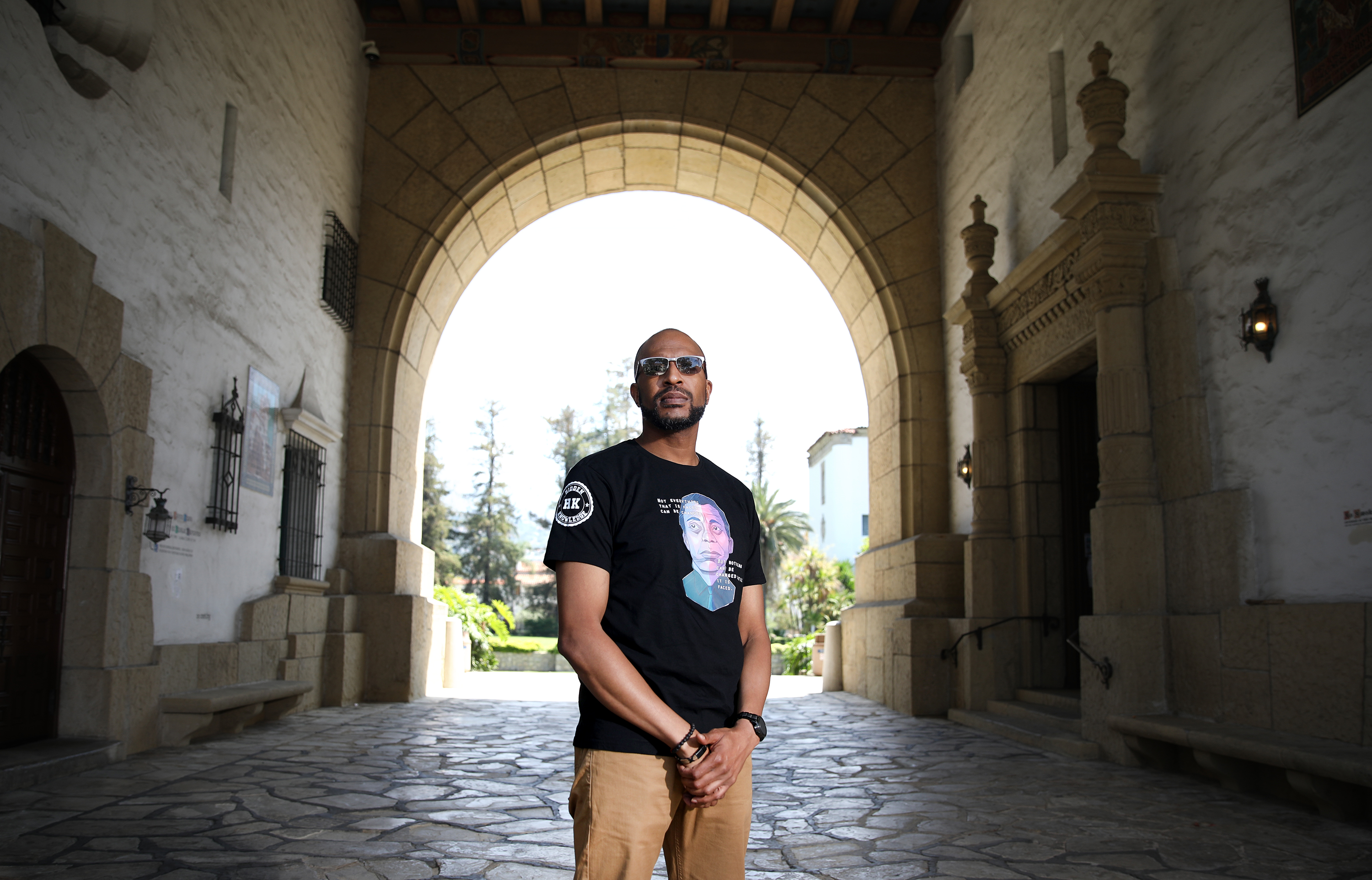

by Jordan Killebrew

Jordan Killebrew | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss

The enduring legacy of slavery, a system that criminalized and exploited Black people, is evident in the persistent inequity, racism, and injustice afflicting our nation.

Despite the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, some states invested in the industry of slavery with active resistance to the emancipation of Black people. It was not until Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, and enforced the Emancipation Proclamation that the last enslaved African Americans were free. As a Black and Queer man, I often think about how my Ancestors must have felt as they processed the meaning of freedom and how they rejoiced in celebration.

The Fourth of July was my favorite holiday growing up. The fireworks, the summer vibes, and what felt like unity among a large nation. In grade school, I was taught about the Declaration of Independence and how our founding fathers fought for freedom — “No taxation without representation” still rings in my mind. I recall flipping through my history books to find one paragraph about my people being enslaved, and a small section on the civil rights era, which I was made to believe was eons ago. I did not learn of Juneteenth until I was in my late twenties, and that was by design.

Juneteenth is now my Independence Day, my favorite holiday. On this historic day, my Ancestors were acknowledged for their humanity, and their survival offered me the opportunity to become their wildest dreams.

I am a proud cofounder of Juneteenth Santa Barbara, along with my mentor friends Simone Ruskamp and Chiany Dri. Our first Juneteenth event was celebrated at El Centro, a small but mighty community center. We brought home-cooked soul food and shared Black joy through our programming. The following year, we partnered with the Santa Barbara Public Library, where our event grew to 400 people, I still cooked my mac-n-cheese (well, a combination recipe between my mother, her sister, and myself), and we showcased the Santa Barbara Black community in full.

This year, to protect our Black community — which has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 — we have turned our event into a virtual festival. We will not allow the Rona to stop our celebration and our continued fight for justice and Black liberation. This shift in venue has offered us a unique opportunity to archive our living legacies. The Digital Diaspora celebration will feature an array of videos of Black community members sharing their stories, showcasing their work, and highlighting our collective histories. Black artists, poets, and professionals have offered to share their crafts, and we will make these videos available through our website, Facebook, and Instagram accounts.

Community organizations and businesses to be featured include Black Rock Coalition, Coffee with a Black Guy, Comfort Food, Cresco Labs, Endowment for Youth Committee, El Centro, Flourish Psychology Co., Healing Justice: BLM SB, Luna Bella, Martin Luther King Jr. Committee, Monkeytail Intelligent Exercise, Moore on Health, Pura Luna Apothecary, Santa Barbara Young Black Professionals, and so many more.

We invite you to join us in community on Friday, June 19, for Juneteenth Santa Barbara’s Digital Diaspora and Santa Barbara Celebration of Black Histories and Futures.

Join us at juneteenthsb.com.

Jordan Killebrew is a cofounder of Juneteenth Santa Barbara. He is a community organizer that has an abnormal love of the community, especially in Santa Barbara. His day job is at the Santa Barbara Foundation while his free time is spent volunteering with local nonprofits. He is a graduate of the University of California, Santa Barbara, and he revels in the pride of being a Gaucho alum. Learn more about him at jordankillebrew.com.

Who Will Educate White People in the Movement for Racial Justice?

Black Lives Depend on It

Who Will Educate White People in the Movement for Racial Justice?

Black Lives Depend on It

by Dr. Donte Newman

Dr. Donte Newman | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss

Often, I hear some black anti-racists say, “It is not my responsibility to educate white people.” For a long time, I could not identify why I rejected that statement. The source of disagreement surfaced during a recent FaceTime call with a friend of mine who vehemently condemned protesters who damaged property.

Wyatt and I have been friends for almost a decade. We met through a high school debate mentoring program where we both volunteered. As life has progressed, time and other obligations have permitted us to catch up about twice a year, but this time, the conversation took a turn to the topic of race. Race has never been a seminal topic, but the civil unrest throughout the country provoked us to share our varying opinions and life experiences. While we share a number of similarities, our lived experiences are different because his skin is white and mine is black.

After the formalities of sharing life updates — marriage, career, and the respective lives of our former students — I noticed this call was different. Wyatt was checking in on me because I am black. As the conversation progressed, Wyatt was keen on sharing his thoughts about the protests and even characterized them as “bananas.” He further stated how he didn’t understand why people were protesting and destroying people’s property.

It was here that the challenge I’d faced all these years was made clear. I had a responsibility to educate my friend on this issue.

An officer who took an oath to serve and protect kneeled on the neck of George Floyd for eight minutes and 46 seconds. The trial, sentencing, and execution of a man’s life took place on a street corner instead of a courtroom, and Wyatt was discussing the destruction of property. Wyatt’s statements, which echoed others throughout the country, condemned the protest and not the murder.

“What do you value?” I asked. He knew what I meant with this question. It was a question we had both asked our students all those years ago. He made the connection. We were not having a conversation about a man’s humanity but our respective values. What is more important: life or property? No longer looking at me, his eyes in a distant glare, he responded, “life.”

The conversation that Wyatt and I had is no different than the millions of conversations happening at dining rooms, chat rooms, and virtual workspaces across the globe. Life cannot be restored, but stores can. When we position property as the most important value in this context, we devalue black lives. This is the purpose of the rallying cry being heard and written across America: BLACK LIVES MATTER.

There is no doubt that the destruction of property is a violent expression of protest, but it is a false equivalence to compare it to the violence against black bodies. This form of protest is a result of being unheard by our criminal justice system. The destruction of property is not a new phenomenon — these practices can be found in notable revolutions in Haiti, France, and even the Americas. The destruction of property is not senseless.

Maybe some black protesters destroy property because historically we have been systematically denied property ownership. Maybe some black protesters destroy property because our humanity was denied when we were legally defined as property. The liberation of oppressed people in our history has always come at the helm of violence. Unfortunately, violence has become a prerequisite for justice.

At this point, we are weeks into an uprising, and America is having a value debate in response to the protests of police violence against black bodies, including the recent murder of George Floyd. The essence of that argument from white America is that property is more important than black life. Dr. Eddie Glaude Jr. says we have a value gap in America. That is, white lives matter more than black lives. Property may be an extension of whiteness, making it more valuable than black lives in the white psyche.

This value gap is important to note. It is important to discuss because as former president Barack Obama states, a change in values can lead to a change in policies. A change in values can also lead to a change in how we enforce policies. But how do you get white people to value black lives? It begins with moving beyond the statement of BLM and addressing the policies that must be endorsed by a change in values.

I understand black anti-racists when they say, “It is not my responsibility to educate white people.” It is not the responsibility of the oppressed to educate and be oppressed by the oppressor. While friends like Wyatt aren’t requesting the intellectual labor to explain the purpose of my humanity, it is incumbent upon me to teach, correct, and inform when opportunities on such topics present themselves.

So while there are some that are not interested in the movement to educate white people, perhaps this is something that we must do, unfortunately, because we value life — black lives. The neglection of this education can literally be deadly for us. I am tired of us dying because of white ignorance.

Educating white people is exhausting; it is tiring; protest is tiring; and even writing this article is tiring, but this is my march for racial justice; this is my protest in the movement; this is my role toward social and political change.

Wyatt and I concluded our conversation in a very different manner than usual. Instead of a goodbye, it was an apology for centering his focus on the protesters and not the purpose of the protest. He is now committed to increasing his knowledge about white supremacy.

Wyatt is not alone. Maybe you have a Wyatt (or you are the Wyatt) in the life of a black friend. Before you start a conversation with your black friend about recent protests, ask yourself: What do I value: life or property?

If you are a black anti-racist, I am not imploring you to join my crusade in educating white people at every hour of the week, because it takes a lot of mental, emotional, and physical bandwidth to do so, but you should in some capacity — and you should be paid because it is intellectual labor.

It is my hope that once you conclude this reading, you too will join Wyatt and me in the responsibility toward educating white people in the movement for racial justice. Black lives depend on it.

Dr. Donte Newman is a communication professor at Santa Barbara City College. He earned his PhD in communication from American University

My Lifelong Search for Liberty and Justice

Every Decision a Black Person Makes Takes into Account the Implicit Bias Inherent in Our Society

My Lifelong Search for Liberty and Justice

Every Decision a Black Person Makes Takes into Account the Implicit Bias Inherent in Our Society

by Victor Bryant

Victor Bryant | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss

When I was a child, I remember taking pride in reciting the pledge of allegiance to begin the school day.

The thought of living in a country that aspires to provide liberty and justice for all gave me a warm, fuzzy feeling inside.

I say “aspires to provide liberty and justice for all” because even as a very young black boy I knew this country did not live up to the pledge’s mandate. I knew I was the ancestor of slaves. I knew that law enforcement could be dangerous regardless of innocence or guilt. I could sense the anxiety caused by the lived experiences of my family. I had heard the stories and seen enough firsthand before I could even read to know that the stories were true.

As a black man, I have had a good and relatively easy life so far. I’m a college graduate. I have a beautiful family. I have no criminal record whatsoever, and I get to live out my passion of sports writing for a publication I believe in.

But I didn’t get here by accident. A figurative village of counselors took me in and molded me into who I am today.

Some of those people were police officers. Al Brown, Bill Lewis, and Hollis Lee were some of my mentors with the 100 Black Men of Orange County’s Passport to the future program during my high school years from 2002 to 2006.

Brown was the chief of the UC Irvine Police Department, Lewis was a sergeant in the Westminster Police Department, and Lee was a retired LAPD officer. We would meet with them among several other black professionals in the community every other Saturday to learn about topics not covered in school such as conflict resolution, black history, financial literacy, and how to interact with police.

These men would debate with us about current events and have us set realistic goals for the future. If a young man said his goal was to play in the NBA, they wouldn’t necessarily shut him down, but they would make him connect the dots with questions. What travel ball team do you play for? Are you on varsity at your high school? Who are your personal trainers? Did you make the all-county team? The questions made sure we stayed on track for whatever our goals were.

If not for the foresight of my parents to engage me in a program that gave me the tools to navigate a society that has yet to come to terms with its original sin, my outcomes could be drastically different.

Systematic racial inequality is sewn into the fabric of our society, and it goes far beyond police brutality or the shortcomings of our criminal justice system overall.

Every decision a black person makes takes into account the implicit bias that is inherent in our society.

I recently noticed that I was taking my 2-year-old son on my walks around the neighborhood, not just because he wanted to go, but because he made me feel safe.

With my son in his stroller, I was no longer a menacing black man, but a loving father as evidenced by virtually every interaction on the street.

When I was 21 years old, I had a gun pulled on me by a police officer because there were the remains of a softball bat under my seat that he considered a weapon. My girlfriend at the time played softball for UCSB, and it was her car. I didn’t even know the bat was there. I was able to calm down the officer and de-escalate the situation, but the trauma remained.

A split second is all it takes for a misunderstanding to become a death sentence.

At the age of 23, I was pulled over five times during that year and never received a ticket. The various officers always had an excuse for pulling me over, but not once had I broken the law. The lessons of officers Brown, Lewis, and Lee were invaluable during those situations.

Unfortunately, every young black man isn’t as fortunate as I am. Their parents almost certainly gave them “the talk” about how to interact with police and stay above reproach, but it may not be enough.

An entire curriculum is necessary to prepare a black person for the pitfalls and obstacles they will face from generational poverty to the not-so-friendly neighbors who are so quick to weaponize the police against us.

The only problem is we can never reclaim that time, energy, and effort. You don’t get back every other Saturday.

The pledge of allegiance no longer resonates with me the way it did when I was a kid. The warm, fuzzy feeling is overwhelmed by a strong dose of reality. We are still fighting for what our parents fought for, what our grandparents fought for, and what generations of black people in bondage dreamed of.

It’s 2020, and we can’t leave this work to another generation. At this point, “justice delayed is justice denied.”

Victor Bryant is a sports writer for the Santa Barbara Independent. He has been a resident of Santa Barbara for 14 years and completed his undergrad at UCSB in 2011. He also serves as a catalog/schedule specialist at SBCC and his wife, Brandi Rivera, is the current publisher of the Independent.

We Do This Work for the Love of Black People

Our Collective Participation Is Required and Urgent

We Do This Work for the Love of Black People

Our Collective Participation Is Required and Urgent

by Simone Ruskamp and Krystle Farmer Sieghart

Krystle Farmer Sieghart and Simone Ruskamp | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss (File)

For Meagan Hockaday

For George Floyd

For Ahmaud Arbery

For Breonna Taylor

For Nina Pop

For Priscilla Slater

For Rayshard Brooks

For the countless others whose names have escaped our lips but whose loss has been deeply felt

We do this work for the love of Black people.

I, Simone Ruskamp, and my organizing sister, Krystle Farmer Sieghart, are two of the parts of the larger Healing Justice Santa Barbara Collective.

As Black femme women, we have stepped into this moment, knowing that we are continuing the work of centuries of Black women who have laid the foundation of this movement by birthing children and nourishing families (literally and figuratively), while strategizing boycotts and defining intersectionality.

We name specifically our Black foremothers and organizers because even now as the trauma and violence of police brutality have come to the forefront, we continue to erase Black women who are also brutalized by police and who often are captured and dehumanized on film as they cry for their children.

Neither Krystle nor I are new to this work. Years of being Black in Santa Barbara and honing our craft in harmful institutions have prepared us for this iteration of community organizing. We were intentional in gathering May 31 to make sure that our work centered first on healing and then on truth telling, partnered with action.

We know how often Santa Barbara likes to congratulate itself, and so we wanted to remind our community that these harms do indeed happen here, and so we named the first Black resident, Jerry Forney, forced here as an enslaved person, and Meagan Hockaday, a former Santa Barbara High School cheerleader later killed by Oxnard police. This happens here.

We have no excuses not to act; and so we must reform and divert resources from the Sheriff’s Office and Police Department, protect and preserve Black landmarks, provide institutional support for celebration of Juneteenth/Black Independence Day, and push our cities to issue proclamations condemning police brutality and declaring racism a public health emergency. We must not fall into the traps laid by performative activism or make caring about Black lives trendy. Black lives and healing matter. Our collective participation is required and urgent.

On May 31, as our “community police” refused to kneel and our mayor used her power to silence Black women, many privileged folks in our community realized for the first time that Black people in our community are not safe. As the officers continued to snicker and glare as we lay on the ground beneath them, the veneer of friendly law enforcement melted, and left remaining was the face of white supremacy. Being confronted with such realizations was terrifying, but Krystle and I have used that feeling to rally our community.

In the short weeks that have passed since, we have gathered community, continued to provide healing spaces for Black folks, and most recently hosted an impactful and fruitful Black community meeting. Now is the time to uplift solutions and resolutions crafted for and by the Black community. Our Black community is deserving of healing. Our Black community is deserving of space. Our Black community is deserving of a Santa Barbara that centers, uplifts and, invests in them.

This is not a moment; this is a movement. Join us.

Simone Ruskamp and Krystle Farmer Sieghart are organizers with Healing Justice Santa Barbara. Find them on Facebook @HealingJusticeSB.

Krystle Farmer Sieghart is a mother, wife, womanist, grassroots organizer, femtor, social justice warrior, and lover of black people, amplifying marginalized voices and building community. She majors in organizational leadership at Los Angeles Pacific University.

Simone Ruskamp is a Black woman who loves Black people. As the parent of a young child, she affirms the radical work of mothering and believes that all are needed to create the communities we deserve.

It’s Time

Coffee with a Black Guy Is Ready

It’s Time

Coffee with a Black Guy Is Ready

by James Joyce III

James Joyce III | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss

It’s time. Yes, it’s about damn time.

From the region that gave birth to the national unrest following the controversial Rodney King trial nearly 30 years ago, and from this great nation that was built on the backs of my damn ancestors: It. Is. Got. Damn. Time!

For the past eight years, I have served our community working in the district leadership for our State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson. And four years ago, following the law enforcement killings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, I launched an initiative called Coffee with a Black Guy, a facilitated community conversation about race and perspective. Simply put: coffee. Connection. Conversation.

I’ve seen Coffee with a Black Guy (CWABG) as sort of an entry point to non-black people’s continuum of racial understanding. The platform that my team and I have worked to build over the past four years is ready-made for this moment that we find ourselves in now.

CWABG offers a simple roadmap that could move us beyond this mass awakening to the very raw and dangerous realities of the racial injustices that plague our land. That blueprint is: Build community. Get involved. And forge meaningful relationships.

There is an urgency to this moment that we must seize to advance the movement.

And, I’ll admit, over the past few weeks, I have been quite “blackishly” skeptical of the newfound incredulousness of our condition, the black American condition. I mean, our culture is pop culture, and all you have to do is listen — throw a dart at a hip-hop song, and the lyrics provide a snapshot into our reality.

“World peace, niggas talk about ‘Don’t shoot!’ / Tell that to police / Scared, ain’t none of them prepared, I could see” — “Who R U?” by Anderson .Paak on his 2018 album titled Oxnard.

“Elvis was a hero to most (x3) / but he never meant shit to me, you see / Straight up / racist that sucker was, simple and plain / Mother fuck him and John Wayne / ’Cause I’m black and I’m proud / I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped / Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps / Sample a look back, you look and find / nothing but rednecks for 400 years if you check / ‘Don’t Worry Be Happy’ was a number-one jam / Damn if I say it, you can slap me right here.” —“Fight the Power” from our brother Chuck D of Public Enemy’s 1988 album titled It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.

Nevertheless, we persist.

These two specially curated glimpses into the black American experience were penned and introduced to the world 30 years apart, but the only things that have changed about that experience are the technological advances those artists — with ties to Ventura County — used to produce their art.

It’s time, but how do we move forward to build community, get involved, and forge meaningful relationships? In the urgency of now, this path forward is imbued with all the pain and pumblings of my ancestors, all the snide remarks unchecked, and all the tears wept. These life experiences add up to be useful in this moment. Turning individual and collective pain into community gain. Turning pain into gain — we’re still doing it.

The economic prowess of our nation in global markets, the reason we can tout California as having the fifth-largest economy in the world, the reason that we are America has been built on the backs of our enslaved ancestors — need I remind you, for free!

And all we, black people, descendants of those who were enslaved, have received in return was an apology from Congress, “on behalf of the people of the United States, for the wrongs committed against them and their ancestors who suffered under slavery and Jim Crow.” — House Resolution 194, passed by the 110th Congress, July 29, 2008.

See, this is why ethnic studies curricula are important.

So, both finally and unfortunately, welcome. Welcome to your arc of better racial understanding. Coffee with a Black Guy is ready. You can explore some of the conversations that we have been having locally at the CWABG YouTube channel and at our website, cwabg.com.

These conversations follow no script, just town hall style. As we ease back into gathering in person, urge organizations that you are affiliated with to have the tough conversations about race, diversity, inclusion, privilege, and perspective. That is genuine community building.

Don’t get me wrong, I do not profess to have all the answers. Hell, I do not profess to have any answers. Nor do I speak for or from the experience of all black people; if you haven’t figured it out by now, we are not a monolith.

But I believe that if we do not at least start the conversation, we are doomed from there on. Please be aware that leaning on your black friend(s) can be traumatic and tiring and can stretch the perimeters of a friendship. I do not make this offering out of obligation, but out of gratitude for the experiences and the ability to view and share them as teachable moments.

Black folks, those of us who are willing, let’s help them out. Hopefully for the benefit of us all. So host a CWABG conversation within your network or community, the way that the Vista del Monte retirement community did last April. Or go back and watch some of the previous community conversations and really listen to learn. From there, that may lead to reading suggestions (S.B. Public Library has compiled an anti-racist reading list), more engaging conversations among a smaller group of willing friends or even a dinner invitation, who knows.

My mother always said that a closed mouth doesn’t get fed. Well, the same goes for you in our current climate.

Engage. Let’s build genuine community. Let’s do better. Let’s be better.

If not only for yourselves, put in the work now for future generations.

My black is beautiful and so are we — community, I share this message in love. —Ashé

James Joyce III currently serves as District Director for State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson and founder of Coffee with a Black Guy LLC. He based this article on a speech he delivered on June 4, 2020, at an NAACP solidarity rally honoring George Floyd at the Ventura Government Center. See cwabg.com (includes links to social media) or linkedin.com/in/james-joyce-iii-00157239/.

Here’s a List of Santa Barbara’s Black-Owned Businesses

Because Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Is Critical for Achieving Community Equity

Leaders of Healing Justice Santa Barbara Collective Speak Out

‘We Have No Excuses Not to Act’

by Tyler Hayden

Owner of Pure Luna Ashe Brown. | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss (File)

Like a lot of Santa Barbarans, Angie Chung wants to walk the walk when it comes to supporting her black neighbors. Lip service comes cheap, she understands, but real change does not. And the immense weight that money carries in shaping and reshaping a community can’t be denied.

To help leverage the power of our collective pocketbooks, Chung, a data analyst, recently created a list of Santa Barbara County’s black-owned businesses. Though the compilation is as comprehensive as possible ― Chung made it by doing online research, talking to friends and coworkers, and soliciting suggestions from the businesses she’d already confirmed with ― she welcomes feedback and is happy to make additions.

Intentionally patronizing these places ― from the Santa Ynez Valley Swim Club to JaniCare Commercial Cleaning in Goleta to Cali 805 footwear in Santa Barbara to Summerland Salon and Spa, and so on ― is a simple but important step toward flattening a historically uneven playing field, Chung explained. “Especially with Santa Barbara having a small Black and African-American community, I find it vital to give support,” she said. The reaction to this list, now making the rounds online and racking up thousands of views, has been overwhelmingly positive. “The local community has truly gone out of its way to speak up and share,” she said.

Chung gave a special shoutout to Lee’s Tailoring on lower Hollister Avenue. “He has always done a great job and in a timely fashion,” she said, “even when I’ve scrambled last-minute to get a dress altered a few days before a wedding.”

Ashe Brown, founder and owner of Pura Luna Women’s Apothecary on Chapala Street, best articulated the financial dynamics at play here in Santa Barbara. “We can’t stress enough how vitally important it is to support black-owned businesses,” she wrote in Pura Luna’s latest newsletter. “We need to help close the racial wealth gap to create more opportunities for meaningful savings, property ownership, credit building, and generational wealth. By supporting black, you help support job creation for other [people of color].”

“When it comes to the wealthy and rich here,” Brown went on, “there is no lack of white money, and thank goodness for Oprah for representing the dream that some black Americans hold for themselves. However, one black woman mogul is not enough. Can we see and create more, please? Your dollar and the way you choose to spend it is powerful. Know that your informed choice and effort to support minority-owned businesses helps us tip the scales to empower our communities.”

In a different but similarly-intentioned economic vein, Councilmember Michael Jordan last Tuesday suggested the city enact a fee or tax to fund social equity initiatives. It could be like the two-percent hotel bed tax that Santa Barbara charges to help pay for environmental programs, he explained.

“The situation we are in, the foundation for it, was based largely on economic gain by others using people of color,” Jordan said. “It could be that if you are going to come visit this city and have the pleasure of being here, you are also going to help contribute to making it a better place for all of our community.”

Santa Barbara’s Black-Owned Restaurants and Food Purveyors

Talking About Race with Entrepreneurs and Chefs from State Street to Lompoc

Santa Barbara’s Black-Owned Restaurants and Food Purveyors

Talking About Race with Entrepreneurs and Chefs from State Street to Lompoc

by Matt Kettmann

Shante Norwood owner of Té’s Tees Bakery. | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss

On June 12, as Black Lives Matter protests rolled through the streets of American cities both large and small, Shanté Norwood received a message from a customer who’d ordered cupcakes for 25 people through her Lompoc-based home bakery, Té’sTees.

“I was just informed that this is a black owned business and with all that’s going on I will be canceling my daughter Heathers order with you,” wrote Brenda Ryan, from Santa Maria. “We are in no way a racists family but I’m sure you and I don’t share the same views and we would like to support a business that does.” (Grammatical errors reproduced as submitted.)

Norwood’s cousin urged her to put the stunning display of overt racism on Instagram. The cancellation went viral, and support flooded to Té’sTees from around the world, with encouragement even coming from Canada and Australia.

“Honestly, I never have had a problem with being a black business owner, or if I did have one, I was very unaware of it — the support I get from the community comes from all different races,” said Norwood, who was born and raised in Santa Barbara, moved to Lompoc in 2000, and started her bakery business in 2017. “That’s why I was very shocked. That was the one and only experience that I’ve ever had as long as I’ve been baking where someone approached me in that manner. ”

Aside from this anomaly, Norwood’s overwhelmingly positive and unimpeded experience as an African-American food purveyor is reflected by the five other restaurant/food service owners that I spoke to from this region. Their names were included on a growing list of Santa Barbara County’s Black-Owned Businesses, of which nearly 60 are featured, with 10 in the food sector, from brick-and-mortar restaurants to home bakeries, food trucks, and pop-ups. (The five I did not contact, due to time and space reasons, are Papa Jay’s Southern Quezine in Guadalupe, Bubba’s Chicken & Waffles and Thai Fast Food in Lompoc, and Cristy’s Cookies and Gipsy Hill Bakery in Santa Barbara.)

Three traditional restaurants with black ownership exist in the City of Santa Barbara: Mollie’s and Embermill on State Street and Petit Valentien in La Arcada Plaza, which was not on the business list as of press time. Neither owner is African-American by upbringing — Mollie Ahlstrand of Mollie’s and Serkaddis Alemu of Petit Valentein are both Ethiopian women, while Harold Welch of Embermill is from the Caribbean island of Barbados. “We still experience the same struggle as black Americans,” confirmed Welch, but none of these three have faced overt racism during their many years in Santa Barbara.

Ahlstrand was most effusive. “Santa Barbara people are so amazing — they are color blind,” said Ahlstrand, who served Italian fare at Trattoria Mollie’s on Coast Village Road for nearly three decades before moving Mollie’s to State Street in 2018. “I’ve been supported by white people for 28 years. I don’t ever think of my color.”

Alemu co-owns the French-focused bistro Petit Valentien with her white American husband, Robert Dixon, and they serve Ethiopian brunch on weekends. She considers their Ethiopian menu an educational affair.

“The major part of the motivation was that Santa Barbara needed a representation of good African food,” said Alemu, who explains that the injera, a gluten-free flatbread made from fermented teff, is the star of the show. “Santa Barbara is a bubble within a bubble. But by having these kinds of businesses that show diversity, they are not only opening up the knowledge about where humans come from but showing that our differences are our strengths. I have been received very, very nicely, and people are trying to convince me to be open seven days a week.”

After cooking at San Ysidro Ranch, La Cumbre Country Club, and elsewhere, Welch opened the Hummingbird Café in Solvang a few years ago and then Embermill on State Street at the beginning of 2020, where he serves healthy, vegetarian-leaning Creole and island cuisine. He said any racial problems he’s experienced are “not on the surface,” and believes focusing on such perceived conflicts do not help achieve success.

“When you think hardcore things along those lines, it can kind of stifle your progression,” said Welch, though he admits he’s lived a sheltered life. “At my house, my mom never used a swear word, never a racist word in my house all of our life, so I never really had an issue with race. But there’s a lot of ignorant people out there.”

Welch described an incident last week in which a man complained about not being able to use a coupon and had a “major meltdown” in front of his whole family. To show him that it was about the restaurant’s no-coupon-at-dinner policy, and not the $25, Welch wound up comping the whole meal. “He was an asshole,” he laughed, “and he was African American!”

A longtime employee at AppFolio by day, Charles Myles is just starting out his food business, combining his dad’s dry-rub-heavy Texas roots and his Lompoc upbringing, where Santa Maria–style, red-oak grilling rules. The downtown resident serves tri-tip sandwiches with vinegar slaw, homemade barbecue sauce, and horseradish mustard at Draughtsmen Brewing Company in Goleta every Sunday under the name Mylestone BBQ.

As such a small, once-a-week operation, he was surprised to be included on the list of businesses, but is using it to his advantage, even if this growing interest in support black-owned establishments only amounts to a “blip.” Said Myles, “I want to make the most out of it. I want to be able to continue to grow and scale this business.”

Like the others, he has yet to see problems due to the color of his skin. But there is an anticipation that barbecue — despite the hours of unseen effort and technical skills that go into getting the meat just right — is supposed to be cheap, a problem that also affects so-called “ethnic foods” across the country.

“It’s not quick; it’s labor-intensive. It takes years and years to be able to get to a point when you can nail it consistently,” he explained. “People assume that it’s supposed to be cheap, and they expect it to be cheaper when they just see me there. That’s the nature of the beast.”

Back in Lompoc, Veronica Van Horn of V’s Sweet Treats runs a home bakery like Norwood does, making specialty desserts such as poodle-topped cupcakes (for a dog’s first birthday party!) and sheet cakes covered in fondant designs of Copenhagen chewing tobacco cans or Air Jordan high-tops. She’s appreciating the extra attention for black-owned businesses, which is leading to more social media likes as well as a graphic designer offering to do her logo for free.

“I would love to open a storefront one day, but of course I need to make sure I have enough people to help me with it,” said Van Horn, whose cooking, which she honed at Allan Hancock College’s culinary program, is inspired by both her dad’s African American side and her mom’s Mexican heritage. “A lot of the recipes are family owned, and I pride myself on making it all from scratch.”

She was “totally disgusted” by the message that went to Norwood, explaining, “You could have used any excuse to cancel gracefully.” But that was the first issue she’s seen in her few years of baking, with deliveries that go from Santa Barbara to Paso Robles.

Norwood, meanwhile, continues to hone her craft, which turns traditional desserts into cupcake form. “If you like peach cobbler or apple pie, I turn that into a cupcake,” explained Norwood, who’d like to expand her business into a cupcake food truck.

Like Van Horn, she’s been attending some of the Black Lives Matter protests in Lompoc and is happy that they’ve been peaceful and productive. “It’s led by a few young black kids, the next generation,” she said. “It’s been so beautiful. We’ve had all races out there protesting with us. It’s good to know that we have that support in this little town.”

Read, Watch, Listen, Learn

Commemorating Juneteenth

Read, Watch, Listen, Learn

Commemorating Juneteenth

by Indy Staff

Juneteenth, 2020 | Courtesy

There are copious books, podcasts, films, and interviews about black culture and experience — far too many to list here. In honor of Juneteenth, Indy staff members Caitlin Fitch, Ricky Barajas, and Ava Talehakimi have put together the following primer, which includes books, videos, podcasts, S.B. Public Library suggestions, and other resources. Dive in.

To Read

Enslavement Narratives

Beloved, by Toni Morrison: The heartbreaking story of a mother who is haunted by her decision to kill her child to protect her from the horrors of slavery.

Kindred, by Octavia E. Butler: A black woman from 1970s U.S. gets whisked back in time to the Antebellum South in order to save her slave-owning ancestor.

Song Yet Sung, by James McBride: Set in the swamps of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, this is a retelling of Harriet Tubman’s life and experiences before her heroic saving of enslaved people through the Underground Railroad.

Interpersonal Racism

Recitatif, by Toni Morrison: A short story that challenges our preconceived understandings of race and class by following the rocky lifelong relationship between a black woman and a white woman, without revealing the identities of either woman.

Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine: A collection of poems and short stories that examine the impact of everyday liberal racism on black people.

Institutional Racism

A Raisin in the Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry: A black family in Chicago with dreams of becoming wealthy meets institutional and interpersonal setbacks in their attempts to improve their lives.

Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis: The former Black Panther discusses the history, function, and future of the carceral system.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander: Jim Crow laws created segregation and oppression but were largely overturned because of the Civil Rights Movement. Alexander examines legislation that has created the prison industrial complex.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot: Henrietta Lacks was a black woman whose cells were harvested by doctors unbeknownst to her or her family to be used for research and experimentation. Lacks was the first immortal human cell line that is still used for medical testing to this day.

Black Feminism/Womanism

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf, by Ntozake Shange: A blend of poetry and playwriting that follows the stories of a group of black women who have suffered oppression for their race and gender.

Ain’t I A Woman? by Bell Hooks: Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex, the book is a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics.

Thick: And Other Essays, by Tressie McMillan Cottam: A series of fearlessly honest essays exploring healthcare, beauty, money, and more through the lens of black womanhood.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou: Beautifully written, this first book in Angelou’s seven-part autobiography follows the author through childhood and her teenage years, as she recalls her experiences of racism, abuse, and trauma, and how she found solace in her love of literature.

White Privilege

Boy, Snow, Bird, by Helen Oyeyemi: A retelling of Snow White that is also an examination of white privilege and how small actions can add up to full-blown prejudices.

The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, by George Lipsitz: Lipsitz refutes the idea that “white” is a meaningless category and discusses the ways in which public policy is shaped by personal prejudices in order to maintain a racial hierarchy.

Me and White Supremacy, by Layla F. Saad: Use this book to, as Saad writes, “dismantle the privilege within [yourself] so that [you] can stop (often unconsciously) inflicting damage on people of colour, and in turn, help other white people do better, too.”

Black Culture/Black Life

Maud Martha, by Gwendolyn Brooks: Told in a series of short memories, Maud Martha is the poetic life story of a black woman in Chicago.

Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi: This multigenerational novel follows the lineage of two Asante sisters — one is taken to America and sold into slavery, while the other marries an English slave trader and remains close to her village. Each chapter follows the story of the next generation and the realities of being black in America during and post slavery.

Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston: Considered a classic of the Harlem Renaissance, this book is set in one of the first self-governing black communities and follows a young woman as she navigates her way through three tumultuous marriages.

Mules and Men, by Zora Neale Hurston: Hurston’s ethnography about African American folklore. It follows two communities in Florida and Louisiana.

Notes of a Native Son, by James Baldwin: In a collection of 10 essays, Baldwin discusses the racial issues that led to him expatriating to Paris, and the racial issues that led to him moving back to the U.S.

The Fire Next Time, by James Baldwin: In two essays, Baldwin discusses the critical role that race has played in U.S. history

The Yellow House, by Sarah M. Broom: Broom’s memoir chronicling her experience growing up in New Orleans East, an often forgotten and predominantly black neighborhood of New Orleans. Her family’s home — a dilapidated yellow house — was destroyed in Hurricane Katrina.

To Watch

Toni Morrison on Racism’s Immorality

Jane Elliott’s “Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes” Anti-Racism Exercise on the Oprah Winfrey Show, 1992

The Godmother of Rock ’n’ Roll: Sister Rosetta Tharpe (2011)

To Listen

Eula Biss: Let’s Talk About Whiteness, On Being with Krista Tippett

Resmaa Meenaken: Race and Healing Body Practice, On Being with Krista Tippett

Santa Barbara Public Library’s Anti-Racist Reading List

White Fragility, by Robin DiAngelo

How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi (check out Kendi’s online essays)

The City We Became, N.K. Jemisin

Parable of the Sower, by Octavia E. Butler

Let’s Talk About Race, by Julius Lester

Online Resources

Curated collection of books for kids on the lived experiences of black Americans

You must be logged in to post a comment.