Santa Barbara County Supervisors Vote to Support Prop. 15

Hotly Debated Initiative Would Increase to Market-Rate Tax for Large Business Properties

Sitting in the Santa Maria hearing room, Supervisor Peter Adam predicted the outcome of the resolution to support Proposition 15, and he was right. Voting along the south and north county fault lines, the county supervisors split 3-2 on Tuesday afternoon to support the state initiative, which requires commercial and industrial properties to pay property tax based on market-rate value assessments. Strong arguments on both sides pitted stressed businesses against underfunded schools and governments — all under the economic strain of coronavirus.

Property taxes in California are currently based on the price paid to purchase a property, and increases are limited to 2 percent per year or the rate of inflation, whichever is smaller. These rules come out of Proposition 13, which passed in 1978, famously to keep “grandma in her home.” That was the recollection of Michel Lynch, a speaker at the debate who remembered the campaign to pass Prop. 13 and shield seniors on fixed incomes from California’s ever-rising property values.

Importantly, residential renters, homeowners, and small business and agricultural lands are excluded from Prop. 15’s increases, Darcel Elliott emphasized, a staffer for Supervisor Das Williams, who brought the resolution to the board. A small business was defined as having fewer than 50 employees, Elliott explained, and those worth less than $3 million were exempt from Prop. 15, as was personal property like equipment and fixtures. Larger companies had a personal property exemption of a half-million dollars.

Get the top stories in your inbox by signing up for our daily newsletter, Indy Today.

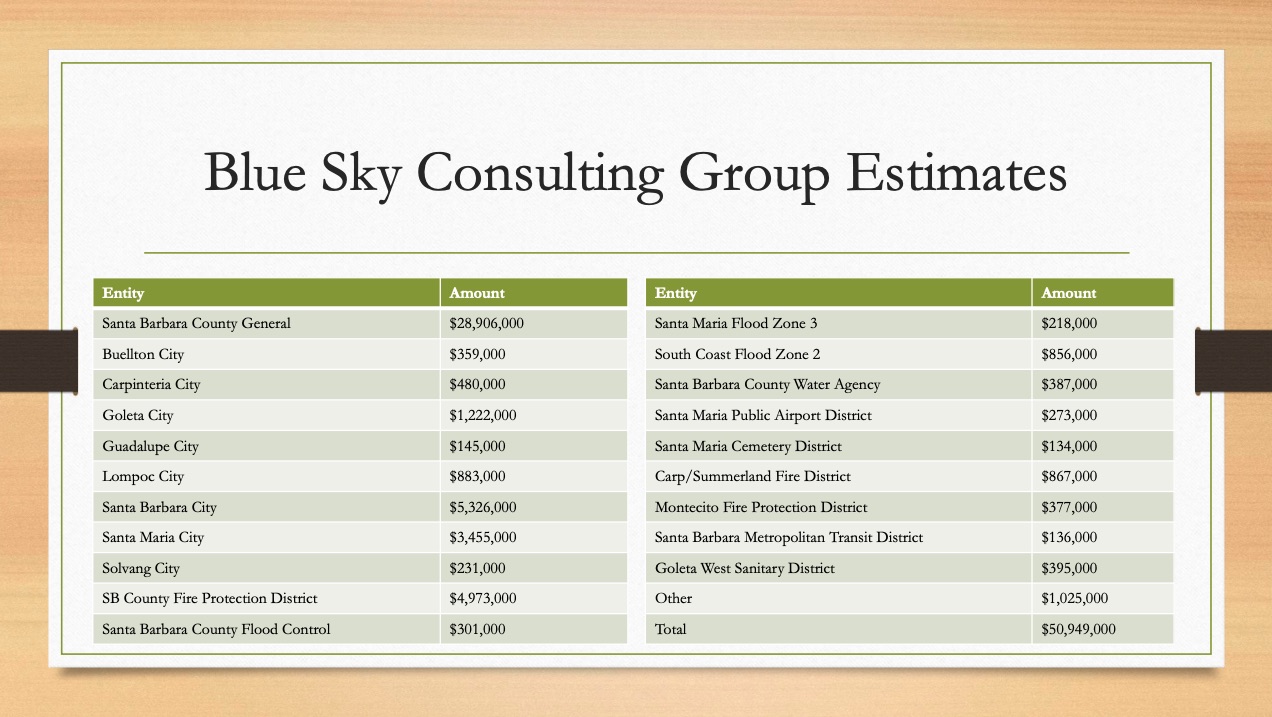

If Prop. 15 were to pass in November, said Elliott, it could raise $6.5 billion-$11.5 billion statewide, to be split 60/40 between local governments and schools, including community colleges. In Santa Barbara County, that could amount to over $100 million among the county and its various cities, special districts, and schools. The $30 million the county’s general fund could receive, Supervisor Gregg Hart observed, would in itself solve the problems of maintaining infrastructure like roads and buildings.

How a market-rate tax would be imposed would be the work of a task force, Elliott explained, formed by the terms of the proposition. Public meetings would include county assessors and businesses to determine how many could get reassessed per year and how long they’d have to pay the new assessment. The increases were to start in the 2022-2023 fiscal year for most businesses and in 2025-2026 for properties at which half or more of the tenants are small businesses.

Supporting the initiative is the League of Women Voters, whose Pam Flynt Tambo told the supervisors the organization had long been seeking to fix the problems of Prop. 13. In the 1970s, homeowners and corporations paid property tax at about a 50/50 ratio to the state. “Now, corporations and industry pay 10 percent compared to 90 percent paid by residential sources,” said Flynt Tambo, because homes change hands more frequently than corporate or industrial lands. “Large industry and corporations benefit from the old low property tax, which effectively discourages new industry from coming into the state,” she said.

Regarding public education and business, Flynt Tambo raised the serious concerns with the ability of schools to educate workers for today’s corporate, industrial, and social climate. As schools’ roles have grown, staffing has shrunk: “Counselors, nurses, and librarians are needed to help children with issues around COVID-19, immigration, and poverty,” she said. California had the largest classroom sizes in the nation, she stated, and had once been 7th in the nation in education excellence; it now found itself ranked “37th or 41st depending on what reports you read.”

What advocates did not understand, other speakers said, was the negative effect Prop. 15 would exert on business, especially when they’ll be trying to recover from the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Although agriculture was exempt from Prop. 15, orchards and vineyards and their fences, irrigation, and barns were not, said Andy Caldwell, who was speaking for the Coalition of Labor, Agriculture, and Business and is running for Congress.

Roy Reed of the County Taxpayers Association noted the increased tax payment would ultimately come from customers’ pockets as costs were passed on from landowners to tenants to consumers. In addition, the proposition funneled away funds that could be used for wages, job creation, and other opportunities, he said.

Coming out of retirement to speak, Mike Brown, who was formerly the county’s chief executive and lives in the Santa Ynez Valley, saw a serious effect for his local gas station, grocery store, and medical clinic. “They’re worth more than $3 million and have more than 50 employees,” he pointed out.

Supervisor Williams argued for the equity the initiative was trying to balance. “If one person who owns a $5 million property pays vastly more than another who owns a $5 million property” — because of the difference in time when the properties were purchased — “that is a preference, not the free market…. It’s wrong to give preference to someone who has owned commercial property because their parents or grandparents owned it,” he said, and it put new entrepreneurs at a disadvantage.

“The next person on that list, I can promise you,” Supervisor Steve Lavagnino warned, “is the individual in a home who is not paying their fair share. The argument will be made, why should you pay a higher property tax when your neighbor is not paying their fair share?” Per-pupil spending was up 23 percent in the last five years, Lavagnino said, “and $72 billion was spent per year on education in California. Throwing additional money at the problem does not work.”

“I’ve been hammered by this debate for the entirety of my political life,” Williams responded. “It would simply be too disruptive for society to change it,” he said of Prop. 13’s homeowner protections. “It’s scare tactics to bring that up,” he added, stating, “If that were brought up for 13, I would oppose it.”

Every day, the staff of the Santa Barbara Independent works hard to sort out truth from rumor and keep you informed of what’s happening across the entire Santa Barbara community. Now there’s a way to directly enable these efforts. Support the Independent by making a direct contribution or with a subscription to Indy+.

You must be logged in to post a comment.