Presidential Race Causes Poodle to Suffer from Insomnia

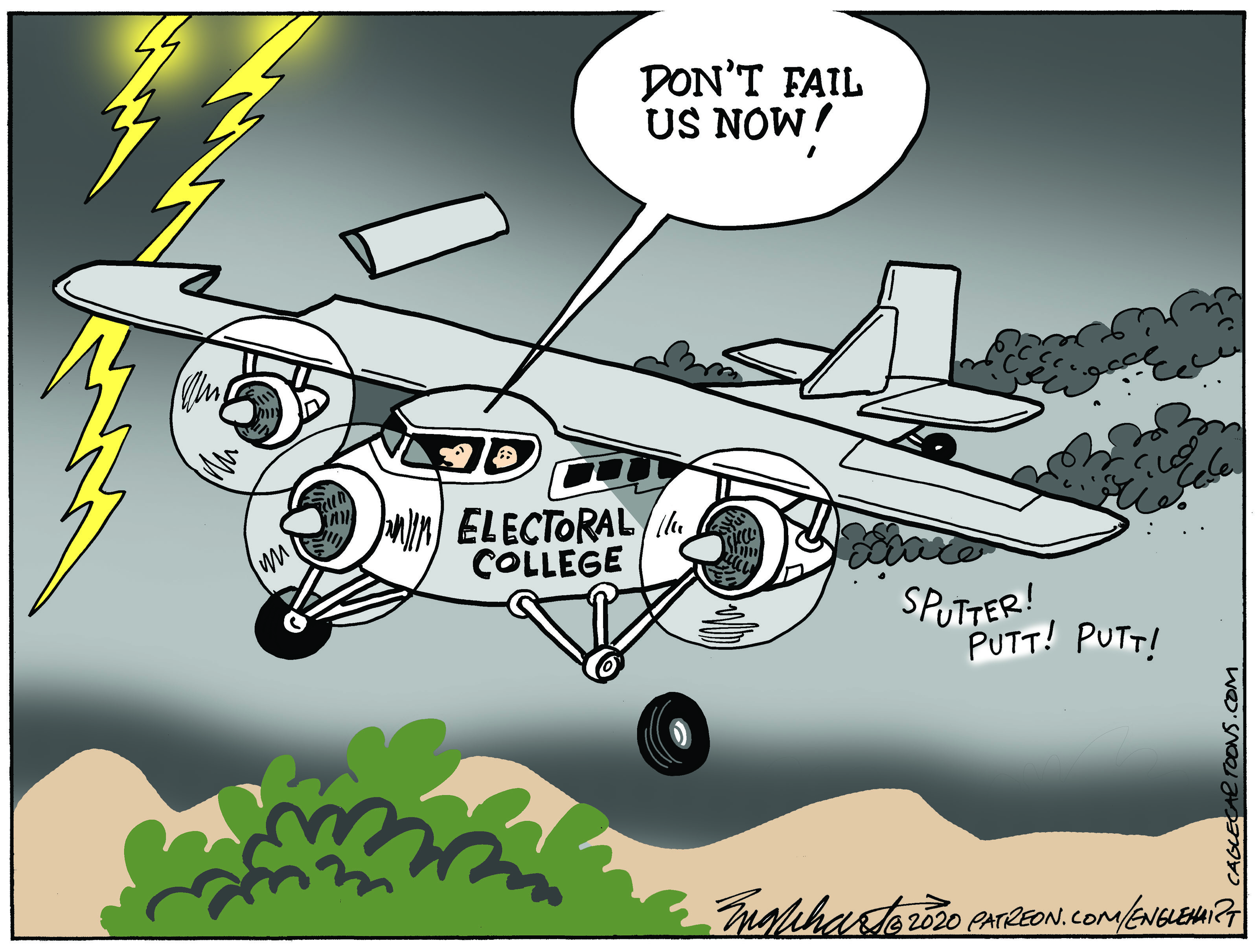

Ain’t No Ambien Strong Enough to Calm Concerns About Electoral College

TICK-TOCK: It was 4 o’clock in the morning when the light switch to my brain suddenly flicked on. Thoughts began crashing about like an avalanche of broken dishes. Worries I’d never had before cried out for mercy. All I wanted was just a little more sleep. Stupid with desperation, I sought refuge in the Internet. I would read up on the Electoral College, a subject so stultifying — I figured — it would quell even the most violent of insomnias.

Or so I thought.

For the record, it has been my lifelong policy not to understand the Electoral College or have any opinion about it. It just is. Feeling one way or the other about it, to my mind, has always been a total waste of time. Only high school debate coaches failed to grasp this.

Again, so I thought.

For those tuning in late, when We the so-called People cast our ballots for president, we are really voting for a mysterious cabal of Electors — now 538 of them — empowering them, in turn to cast the deciding votes for El Prez. The first candidate to get 270 votes wins all the marbles. All this is laid out in the Constitution, also great reading for those struggling with fitful sleep disorder.

All this is acutely pertinent because just four years ago, the candidate who “won” the race in the Electoral College lost the popular vote by three million ballots. Sixteen years before that, the person who “won” the electoral vote — with a major assist from the Supreme Court — lost the popular vote by nearly 550,000 ballots. That’s two times within spitting distance of recent memory. That’s a lot of lightning striking twice. In fact, since this whole thing started, five presidents have ascended the throne having lost the popular vote.

Maybe all this informed my insomnia.

There are, of course, many reasons the Founding Fathers created this complicated Rube Goldberg electoral contraption to elect the person who will become the single most powerful person on the planet. At the time the Constitution was written, serious doubt was expressed whether The People — even property-owning white males — could be entrusted to make a properly informed decision on so weighty a national matter. Accordingly, a proposal to allow direct popular voting in presidential elections was shot down by the representatives of the original 13 states by a score of 12 to one.

Likewise, it was recognized Congress could not be assigned the task of electing the President. That would be way too cozy and incestuous, obviously jeopardizing the whole “three co-equal branches of government” thing, not to mention the separation of power.

But the real reason was slavery.

When the Constitution was being drawn up, southern slave states worried for good reason that by joining the “more perfect union,” their “peculiar institution” would be put at some risk should northern abolitionists seek to meddle, as they inevitably did. At that time, the plan was to assign to states a number of congressional districts based on their population. This would become the basis by which the number of Electoral College electors would be assigned as well. This formula, however, left slave states at some risk. Although northern and southern states had roughly equal populations, 40 percent of the southern population was composed of black slaves who were not allowed to vote.

The southern solution — ingeniously diabolical — was to count each slave as three-fifths of a person for purposes of assigning Electoral College electors and congressional districts. Without this now infamous “three-fifths compromise” — which delicately never mentions slaves or slavery, by the way — the Constitution would never have gotten ratified.

This empowered southern states far beyond what their numbers — at least of free persons — warranted. In 1800, Pennsylvania, for example, had 10 percent more free persons than Virginia, but Virginia — with slaves making up 60 percent of its population — had 20 percent more electoral votes. In fact, Virginia’s electoral lock was so tight that Virginians — all slave owners, by the way — occupied the White House during 32 years of our first 36 years as a nation.

Pretty damn peculiar.

The Civil War came along in 1861. Four years later, Lincoln freed the slaves. And for about 10 years after that, Union troops occupied the South. Black people could not only vote but also hold office. Then came the presidential election of 1876. A Democrat you never heard of named Samuel Tilden of New York solidly beat a Republican named Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote. Tilden’s 4.3 million votes won him 51 percent of the vote; Hayes’s 4 million got him 48 percent. Not even close. But a knock-down, drag-out dispute over the fate of 20 electoral votes — involving South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana — called into question the election’s outcome. Eventually, Tilden and the Democrats would agree to give the White House to Hayes if — and only if — Hayes and the Republicans would agree to withdraw federal troops from the South.

Once that happened, Southern whites unleashed a multigenerational reign of terror on southern black people — Ku Klux Klan I, Ku Klux Klan 2.0, Jim Crow, segregation, and about 4,000 black people lynched — that lasted pretty much until 1965 with the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

How peculiar can we get?

The Supreme Court, of course, is charged with safeguarding the sanctity of all our voting rights, and with them it’s been a slippery slope strewn with banana peels ever since 2000. That’s when the Supremes stopped the recount then taking place in Florida — in which just 537 ballots would determine the outcome of an election in which more than six million were cast — effectively giving the election to George W. Bush. Though Bush lost the popular vote by about 550,000 votes, the Supreme Florida ruling gave him victory at the Electoral College by just five electoral votes.

The moral of the story, I would think, is obvious.

Vote.

And don’t forget to wear a mask.

And of course, go Dodgers.