The Day Santa Barbara Police Racially Profiled Three Harlem Globetrotters

‘Sweet Lou’ Dunbar Recalls the 1983 Incident and the Psychological Wounds It Left

On November, 13, 1983, Santa Barbara police racially profiled three members of the Harlem Globetrotters – Jimmy Blacklock, Ovie Dotson, and Lou Dunbar – who were in town for an exhibition game against the Gauchos.

Blacklock, Dotson, and Dunbar were forced out of a taxi at gunpoint, handcuffed, and made to lay face down in the middle of a downtown street. The detainment lasted for over 30 minutes.

“We had gone downtown just to look around,” remembered Dunbar, now 68, from his home in Houston, Texas. “We got an ice cream, hailed a cab, and then we heard sirens.”

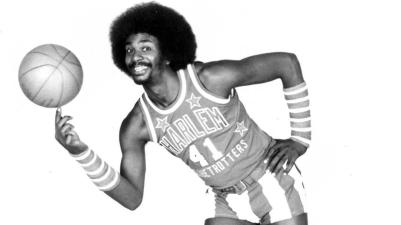

Thirty-eight years later, Dunbar, a gregarious 6’10”, with a disarming laugh, recalls the day – down to the smallest detail – with the same accuracy as one of his famed long-range hook shots.

“We thought a fire truck was coming, so we pulled over, but nothing came by,” said Dunbar. “I looked to my right, and there was a guy pushing the door open of an unmarked car with a pistol out the window. Immediately I put my hands in the air. In an alley to the right of me, there were policemen with shotguns.”

“They filed us out of the car one by one,” Dunbar continued. “I was in the front seat, and they made me slide out the driver’s side. If you look at the [news footage], you can see I only have one shoe on. I was wearing flip flops, and one fell off when I was getting out of the taxi. I thought to myself ‘I’m not about to be an accident reaching for my flip flop.’”

The Globetrotters, just back from Australia and in the early stages of a West Coast tour, aroused the suspicion of the Santa Barbara Police Department, apparently, for the crime of wearing jewelry while Black.

“We had a jeweler in Melbourne at the time who made us custom stuff,” Dunbar said. “And we had stopped in a jewelry store downtown.” The official reason Santa Barbara Police gave for the detainment: suspicion of armed robbery.

“I thought there was going to be another robbery,” Lt. Robert Strong, who set the encounter into motion when he spotted the three Trotters at the jewelry store, said at the time, in reference to a recent Montecito robbery that left $300,000 missing and one dead. “[I thought] that there were going to be more dead people.”

The problem: the Montecito suspects were described as average height. Something the three Trotters could hardly be confused of being. “They said three Black guys of average height,” Dunbar remembered. “I’m 6’10”, Ovie is 6’5″, and Jimmy is 6’2″ or 6’3.””

Blacklock, Dotson, and Dunbar were separated and held in police cars until the owner of the Montecito jewelry store arrived and identified them as not being the men responsible for the robbery and murder.

“They never asked us for our identification,” Dunbar said. “I asked the driver of my police car what we were supposed to have done. He told me, ‘Be quiet. We will tell you later.’”

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

The sad irony of the situation for Dunbar is he came from a family with a law enforcement background. “I never had anything against the police; my dad was a deputy sheriff – he was the first Black deputy sheriff in my hometown [Minden, Louisiana],” Dunbar said. “I was all about doing the right thing.”

Dunbar, known among Globetrotters fans as “Sweet Lou,” said his personality made him a natural fit as a basketball showman. He also cited the childhood experience of touring a local jail as to why he never wanted to step outside of the law. “I thought as a kid, I’ll never be stuck in one of these places,” Dunbar said.

In the year that followed, Blacklock, Dotson, and Dunbar filed a $3 million lawsuit against Santa Barbara, asserting they were targeted because of their race. An appearance by the trio on the Phil Donahue television show made the story national news. A settlement was reached in 1984, reportedly for $75,000.

“I would really have liked to put on our side of the case so the jury could appreciate the state of mind of the cops involved,” said attorney George Franscell, at the time, representing both the police department and the city. Though financial restitution was made, psychological wounds lingered on.

“We weren’t prepared to be put in a situation like that,” Dunbar said. “We had no idea what was going on; we were just out having a good time. It weighs on you: when you have guns pointed on you from all different directions and you don’t know why.”

Years later, as a father, the incident remained in the back of Dunbar’s mind when he talked with his children about race. “I told them, ‘You have to expect you aren’t going to be treated the same,’” Dunbar said.

Thirty minutes in Santa Barbara hardly define Dunbar’s more than 40-year career with the Globetrotters, but they are forever part of the team’s complicated legacy of racial discrimination.

As the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement has pushed police brutality and reform more and more into the national discourse, Dunbar has often found himself reflecting back on that day in 1983.

“I told somebody, ‘At least we are still here to talk about it,’” Dunbar said. “Some of the other guys can’t talk about it.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.