Pano: ‘The Beatles: Get Back’ Documentary and Sansei Art in Monterey

Direct Cinema Proves Durable in ‘Get Back’

This holiday season, we’re bringing you the best in our newsletters from 2021. Sign up for content like this and more here.

Peter Jackson’s masterful new Beatles documentary on Disney+ offers the latest instance of documentary film’s most tenacious underdog subgenre, direct cinema. In this school of filmmaking — otherwise known by its fancy French name, cinéma vérité — the footage is everything. With no voiceover, minimal intertitles, and subtitles only when necessary, direct cinema seeks to tell stories by sight and sound alone, relying on the editing of unscripted raw footage to shape the viewers’ understanding of the material. Lightweight, portable 16m cameras with synchronous sound made direct cinema possible, while adventurous documentary auteurs like Jean Rouch, Haskell Wexler, D.A. Pennebaker, and Frederick Wiseman made it popular.

What’s incredible about The Beatles: Get Back, beyond the in-depth portrait it offers of the group in a period of creative ferment, is the fact that it exists at all. The footage Jackson had to work with is now more than 50 years old. Very few people had seen any of it, and it’s great. The color cinematography competes with the best work in the genre. The Beatles, with their colorful jumpers, distinct personalities, and ability to create fabulous music in real time, offer an ideal subject. Perhaps stranger still is that in the year 2021, the audience feels ready for it, all eight hours of it. Even a decade ago, the suggestion of a Beatles doc with the pacing of a Frederick Wiseman film might have seemed eccentric. Today, with a decade of practice binging direct-cinema-derived television shows like The Office, it hits a sweet spot, especially during the pandemic-inflected holidays.

Whether or not this will appeal to everyone, it’s pure enjoyment for those who would like nothing better than to hang out with the Beatles for a few days or even the better part of a month. The flood of visual detail added to the audio record brings the entire cast to life, not just the Fab Four. Yoko kisses John during a take, and you think, “Wait,” but then it turns out that she’s sharing the news that her divorce has just gone through. Linda Eastman McCartney shows up with her daughter Heather from her previous marriage to a Tucson-based visual anthropologist Joseph Melville See Jr. The little girl charms everyone in sight while frolicking through the studio, and somehow the line “Jojo left his home in Tucson, Arizona” winds up in the song “Get Back.” The fondest wish of every direct cinema viewer is the unforced epiphany, and plenty of these bubble to the effervescent surface of this film, often when least expected.

The final sequence detailing the famous concert on the roof that marked the group’s last public performance plays like an unconscious homage to the world of performance art represented by Yoko. The bobbies show up in the same chin-strapped helmets they wore in A Hard Day’s Night, only this time, it’s “real.” Jackson’s use of split-screen in this episode has roots in the original period of direct cinema’s rise — triple frames are a frequent sight in Woodstock, for example.

And then there’s the music, which is transcendent. When all the stops and starts, the hesitations and substitutions are over, the songs — “Don’t Let Me Down,” “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “Let It Be,” “Old Brown Shoe,” even “The Long and Winding Road” sound better than ever. It’s as though witnessing the creative process had cleaned and restored our perception of the freshness and ingenuity that made them so great in the first place.

This edition of Pano was originally emailed to subscribers on December 1, 2021. To receive Charles Donelan’s arts newsletter in your inbox, sign up at independent.com/newsletters.

Shadows from the Past

January 2022 marks the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. This federal ruling directed the United States military to forcibly evict 120,000 Japanese American citizens from their homes and intern them in heavily guarded camps. Now’s a good time to look at the accomplishments of the Sansei. The Sansei are third-generation Japanese Americans — the grandchildren of Japanese immigrants — and the last generation that can claim direct knowledge of the camps, mainly through the experiences of their parents, the majority of whom were interned.

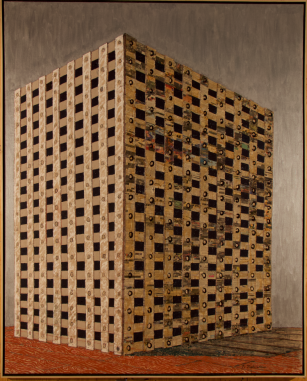

Shadows from the Past: Sansei Artists and the American Concentration Camps, an exhibition at the Monterey Museum of Art on view now through January 9, 2022, features the work of eight extraordinary Sansei artists who have taken on the burden of representing and interpreting this ongoing trauma.

Dense, lyrical, and profoundly moving, Shadows from the Past provides ample evidence of the social courage and emotional complexity of Sansei as a generation. The artists include Jerry Takigawa, Masako Takahashi, Reiko Fujii, Wendy Maruyama, Tom Nakashima, Lydia Nakashima Degarrod, Lucien Kubo, and Na Omi Judy Shintani. Visiting the Monterey Museum of Art is a great experience and highly recommended.

Whether or not you can make the trip, if you are interested in the subject, plan to attend the fourth annual Art of the State Symposium, conducted in person at the museum and online on January 8, 2022. The topic for this year’s conversation is Beyond Identity Aesthetics: Critical Conversations with California’s Asian American Pacific Islander Arts Communities. For more information and to plan your visit, go to montereyart.org.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.