Poodle: Spitting into the Winds of Santa Barbara History

City Commissioners Wrestle with De la Guerra Plaza: Plaza Wins

AIN’T OVER TILL IT AIN’T OVER: They didn’t just throw the baby out with the bathwater; in fact, they all but tossed the bathtub out the window, too. The “they” in this case happens to be the City of Santa Barbara’s Historic Landmarks Commission which spent the better part of Wednesday afternoon chewing up and spitting out key details of long germinating plans to give De la Guerra Plaza — nothing less than the historical, cultural, and political nucleus of the atom that is Santa Barbara — a massively major makeover.

I’m not making fun of anyone here. It’s an admittedly impossible task. That “they” — a hodgepodge of city planners, consultants, ad hoc committee members, the commissioners themselves, and passionately pissed-off members of the public —managed to get this far into three years of meetings, hearings, and non-stop outreach without imploding is compelling evidence of their collective gastrointestinal fortitude.

People have been trying and failing to “fix” what ails De la Guerra Plaza ever since Santa Barbara’s current City Hall was first built in its present location back in 1924. There’ve been no shortage of brilliant suggestions along the way, my favorite being the plan to build an underground fallout shelter on the site (in case of nuclear attack) along with an underground parking garage. That dated back to 1963 when duck-and-cover drills passed as calisthenics. It was not clear just where the fall-out shelter would be in relation to the parking garage, but it illustrated one powerful truth: Even in the midst of nuclear winter, wheels were essential.

That none of these plans ever got adopted reflects the irreconcilable tension that’s existed between our desire to accommodate the automobile and our countervailing fixation with a beguiling historical fantasy rooted in white stucco walls and red tile roofs. Over the years — or at least since 1924 — people would argue about what to do with the plaza — now a large, elongated horseshoe-shaped patch of dead grass surrounded by a few palm trees and punctuated by a flagpole of monumental dimension — and then just give up.

Usually, they’d get distracted by such things as the Earthquake of 1925, the Depression, or World War II. In the meantime, the plaza would just lay there, a quiet, happily neglected green space with boatloads of unfulfilled promise and potential where people could eat their lunch on the park benches while enjoying the abundance of Santa Barbara’s sunshine.

All this, of course, would be interrupted every year at Fiesta when the plaza became “El Mercado!” home to every torta maker, lemonade squeezer, and cascarone peddler in the tricounties, not to mention a stage for every singer, guitar strummer, and flamenco dancer over the age of 4 years old. In times of political tumult, the plaza — like the Sunken Garden of the courthouse — is where those who feel things passionately would go to speak their piece.

In other words, the plaza has functioned — whatever its aesthetic deficits — as Santa Barbara’s front porch and living room at the same time. No wonder nobody could fix it.

The latest plan — did I say three years in the making so far? — is by far the most ambitious, most visionary, and most problematic. It envisions a new plaza cut off almost entirely from State Street traffic. Only the fewest possible parking spaces would remain. It would become a bustling beacon of pedestrian activity, an inviting interface between the community and its City Hall. It would offer a pop-up venue for all sorts of arts and cultural events, a stage for all seasons.

So far so good.

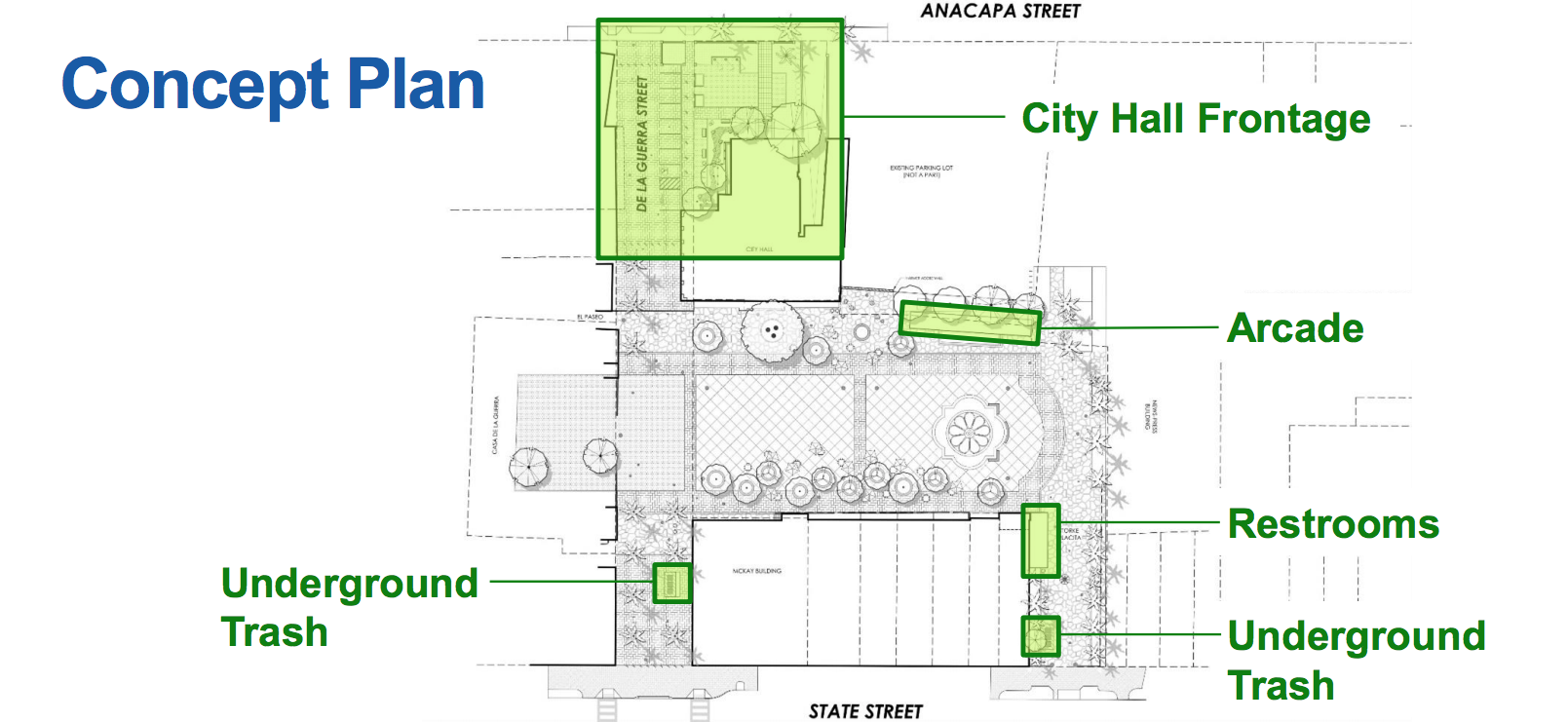

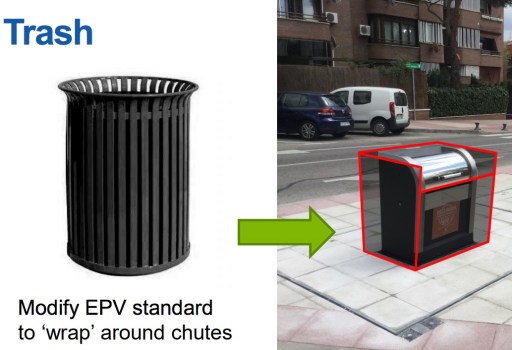

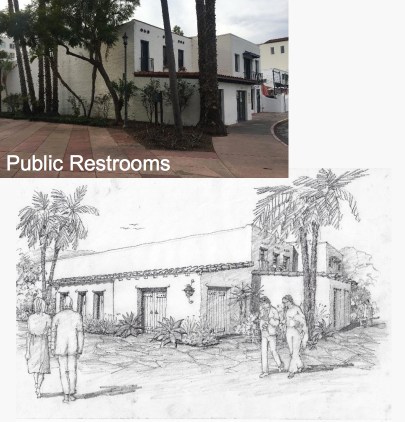

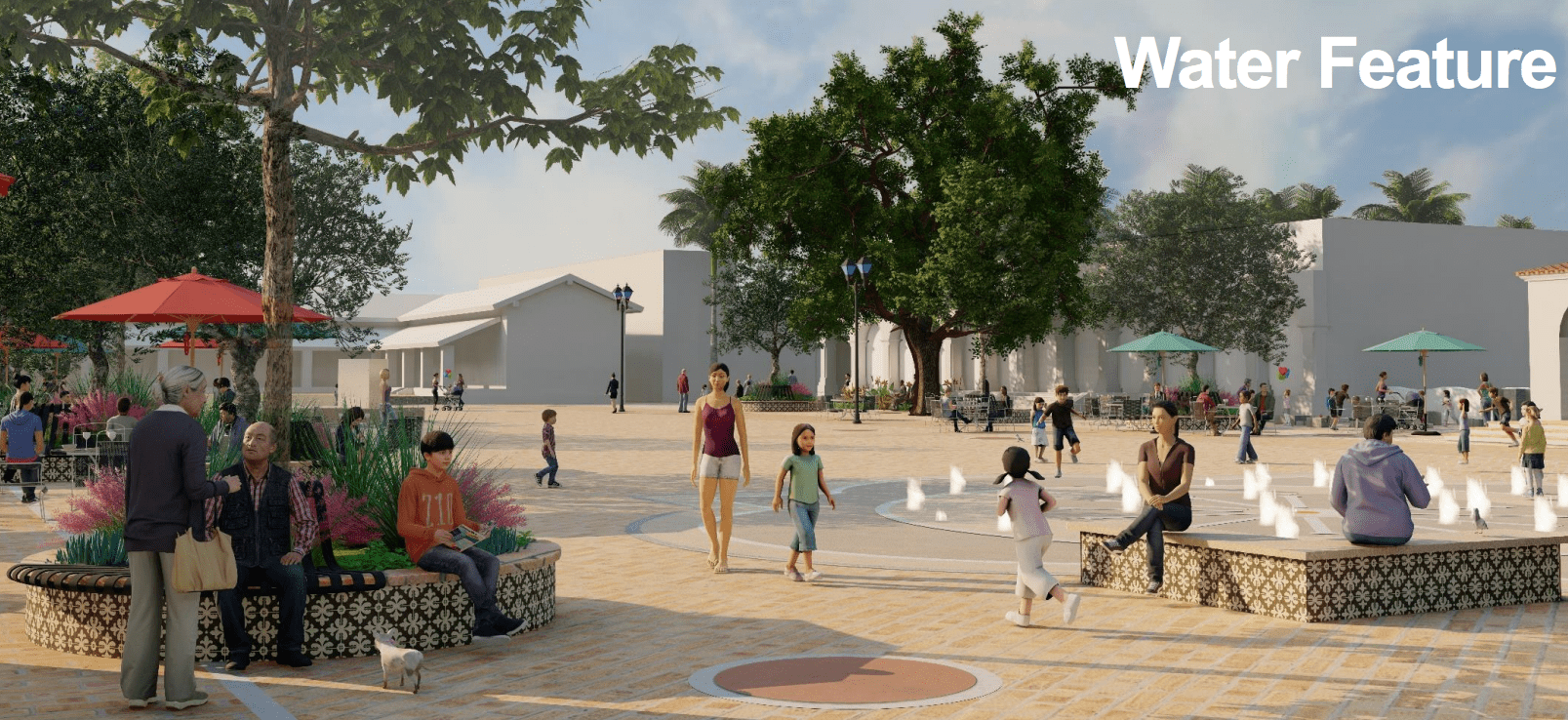

The devil is, of course, in the details, and the biggest detail here is that the lawn — dead as a doorknob as it admittedly is — would have to go, replaced instead with hardscape surfaces that would be flush with the street. Embedded into this hardscape surface would be a multitude of tiny little water jets — known as splash pads — that create a happy spray ground for the kids and a pleasant “white noise” for their grandparents. Located between City Hall and the News-Press fortress would be a new arcade, 100 feet long and 11 feet deep, with arches that mimic the arcade arches that currently exist at City Hall. Jutting 15 feet out from the middle of this arcade would be a new pavilion stage — about 18 inches high — for performers. Quarters for new public restrooms would be built onto the side of an existing structure abutting the Placita that connects the Plaza to the 700 block of State Street. Somewhere in all this will be some new semi-submerged trash containers that are so high tech and European that no one will know they’re even trash containers.

That, at least, was the plan reviewed by members of the Historic Landmarks Commission during what was their third bite at this very large apple. Before they got to weigh in, they heard from several members of the public who had very strong opinions, none of them positive. Lanny Ebenstein, one of Santa Barbara’s reigning philosopher kings, said the proposed changes would “obliterate” the plaza, not revitalize it. Ebenstein — typically congenial to a fault — was unusually combative. If the commissioners approved this plan, he vowed to collect the signatures to take it to the ballot box. “The people do not want to lose the lawn in De la Guerra Plaza. Period. You can take that to the bank,” he proclaimed. “One hundred years from now, there will be a lawn on De la Guerra Plaza,” he vowed, adding, “Be prepared to face the will of the people.”

Others warned that the splash pads would serve merely to attract the homeless who would use the jets to bathe, brush their teeth, and wash their clothes. The water, one speaker cautioned, would become unusably toxic. Another speaker predicted that the public restrooms proposed for the Plaza would be even worse than the ones by the Fiesta Five movie theater. He described having run a gauntlet of homeless people in order to use that restroom, only to find a bottle of pills spilled over the floor and papers strewn throughout the inside of his stall. He was, he said, afraid.

Other speakers complained that the proposed new arcade was too big, too grandiose, and would both undermine and overwhelm City Hall itself.

The elephant under the rug, of course, is the News-Press building — which helps anchor the plaza — and its owner, Wendy P. McCaw, whose hostility to the occupants of City Hall has been exceeded only by the steadfastness of her refusal to engage. A number of questions were asked about “the due diligence” undertaken by City Hall in getting McCaw — whose property will undeniably be affected by any of the proposed changes — on the phone. “I continue to do outreach to the News-Press,” stated city planner Brad Hess, who is bird dogging this project. “All I can say — it hasn’t been reciprocated.”

Cassandra Ensberg, a prominent architect in town, tapped into the history of previous improvement efforts targeting the plaza; they’d always been superseded by more cataclysmic concerns, she noted. In this case, she stated, a more pressing concern was the health and vitality of State Street, homelessness, and keeping downtown alive. Any planning for De la Guerra Plaza, she argued, should take a back seat to the high stakes visioning process now getting underway for the revitalization of State Street. Only when that context is set, Ensberg argued, would the commissioners know what changes made sense for the plaza.

By the time the commissioners got around to weighing in, the hour had grown late. One had already left, not expecting the meeting to have run so long; another said he had to get home soon to take care of his mother, and another warned he expected to fall asleep within the hour. As a body, they’d grown even more peckish than they are frequently accused of being. Still, they seemed clear on a number of key points.

None of them liked the proposed new arcade the way it was designed. All agreed it was too big and too overwhelming. A few thought the idea was unsalvageable and should be gotten rid of altogether. While many had initially supported the notion of creating a new lawn-free public space, many had clearly changed their minds.

“The lawn is what needs to be there,” insisted Ed Lenvik, the senior member of the commission. Lenvik is also perhaps the most outspoken member of a commission famous for speaking its many minds. “I don’t think the proposal we’re seeing is responsible or appropriate to Santa Barbara,” he declared. He then reminded his fellow commission members of a famous paper written by a famous California preservationist architect named Milford Wayne Donaldson. The paper was entitled, “Why Gringo Plazas Don’t Work.” Lenvik repeated the title a few times for dramatic effect but never explained exactly how it applied. Perhaps it was self-evident.

As to the water element, as the splash pads are officially described, there was little enthusiasm but plenty of doubt among the commissioners. Only commission chair Anthony Grumbine expressed any openness to the idea, but he acknowledged his was a lost cause. Commissioner Michael Drury reflected the broader opinion, stating, “I would like to see grass.” He then added, “I don’t support the water feature at all. This is a place where people can go and not worry about kids running in the water.”

The city planner assigned to herding this Mission Impossible project through the process, Brad Hess, seems to have an appetite for political hot-potato projects, like relocating the Farmers Market to make way for the new police station. Knowing his audience, Hess didn’t seek to rebut any of the commissioners, but he did ask for the opportunity “to make a few clarifications.” And they were significant. He pointed out, for example, that the restrooms proposed for De la Guerra Plaza are engineered to automatically clean themselves after each use; consequently they could not get as grotty as the ones described by the Fiesta theaters on State Street. As for the decision to remove the grass and replace it with hardscape, Hess noted that the plaza has to be fenced off for at least three months a year so that the grass — such as it is — can recover from the pummeling it endures during Fiesta. How does erecting orange plastic fence to keep the public off the “lawn” for a 12-week period, Hess wondered, equate to an increase public access?

Good question.

In the end, all was not lost. The commissioners all agreed they liked the pedestrian-only aspect of the new plan; they agreed they liked much of the proposed landscaping; they agreed the surface of the plaza should be flush with the street; and they agreed that De la Guerra Street should be blocked off from traffic.

As for the rest, they agreed they wanted to keep working on it. Even if it winds up taking 100 years from when City Hall was first built, they agreed they want to be the ones to solve the riddle of what should be done with De la Guerra Plaza.

One hundred years might not be quite enough.

To the extent they didn’t throw the bathtub out with the baby, that’s the bathtub.

You must be logged in to post a comment.