I Live in Summerland

Retrieving a Measure of Community Character from the 101

Not long ago, saying “I live in Summerland,” would trigger a puzzled “where?” Then someone would mention the Big Yellow House. Had the restaurant then been empty and a shade of white as today, the landmark might have been the enormous LIQUOR sign looming over town. The next to dog Summerland just might be a truck-stop-sized new gas station canopy and sign.

If there were a lost and found for towns with missing identities, Summerland would be there. Surges of exploitation have repeatedly muddled the town’s character. Current make-believe descriptions include hamlet, nestled, quaint, casual, burgeoning, seaside haven, design destination, comeback community, and chic, convenient, and artsy.

Through the years, Summerland has suffered from labels like “Seventh Heaven,” “Spooksville,” “Bohemian,” “where the debris meets the sea,” “the unwanted stepchild of Santa Barbara County shoved off to the side and forgotten,” “the next Laguna Beach,” and “Baja Montecito.” In an iconic, long-exposure photo, a sleepy Summerland is pictured laid-back beside the Pacific Ocean above a stream of dazzling commuter lights and railroad tracks, with everything looking quiet and intact. Jeez!

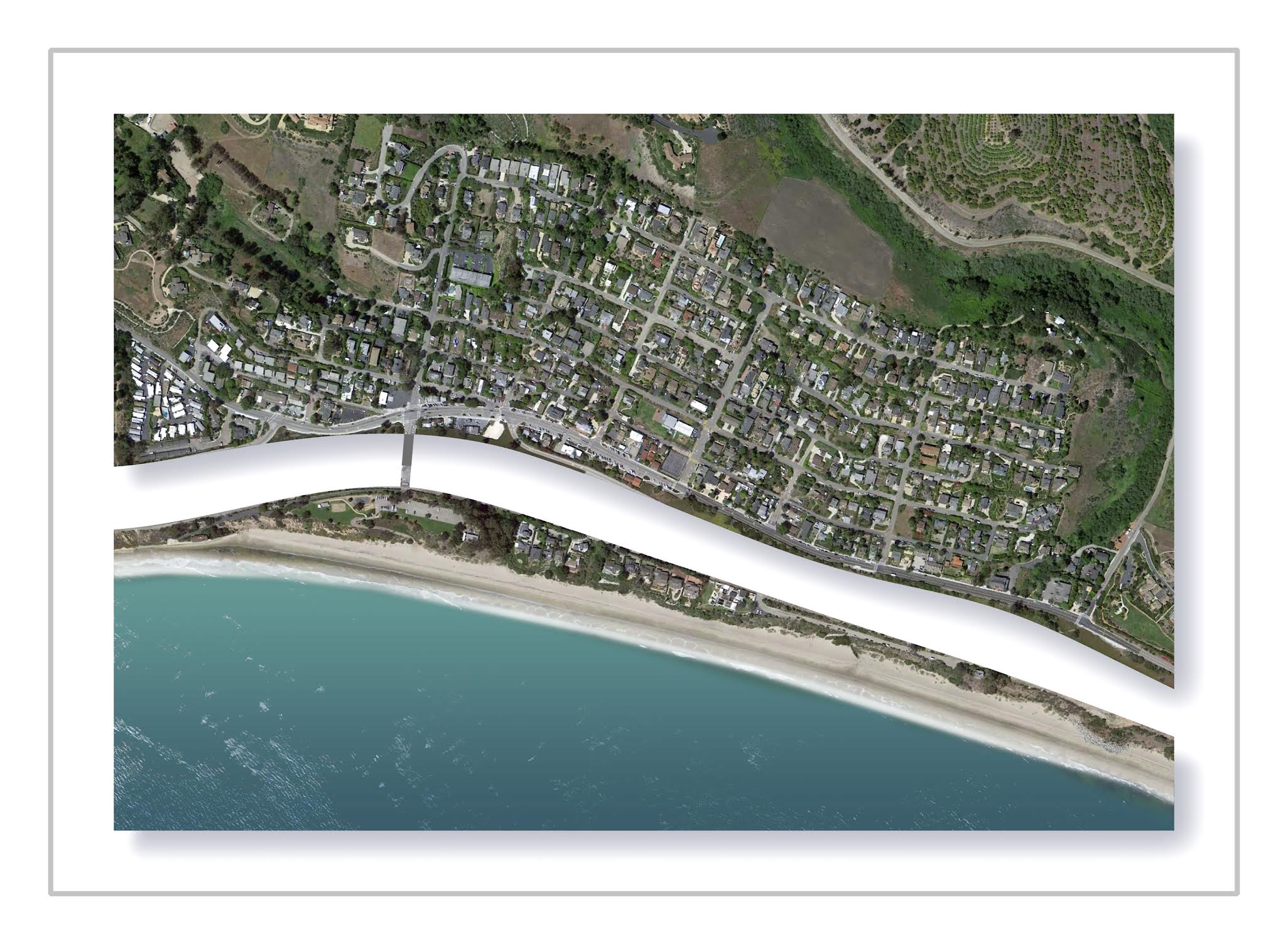

Summerland lost much of its presence and peace to Highway101, its main street and blocks of residential streets to the needs of commuters, its ocean sounds and fresh breezes to traffic noise and soot. The best of Summerland’s bluffs and chunks of beach went to the railroad, its water district and most of Ortega Ridge to Montecito, control of its fire department and school to Carpinteria, and its downcoast to a Padaro Lane “private” beach. Summerland’s eastern flank became who knows what when that far-removed-from-Montecito side of Summerland was dubbed Montecito Ranch Estates, and the adjoining sod-farm, Montecito Oceanfront Polo Estate.

The integrity of Summerland’s neighborhoods is being compromised by short-term rentals; the local context of downtown by whitewashing; the solace of a beach walk by vacationers, glamour photographers, e-bikes, and dude strings of selfie-taking horseback riders. Santa Barbara’s touted, southern gateway–from the Rincon to the city–is gentrifying and dragging Summerland along.

A rare opportunity to address Summerland’s persistent struggle with identity came a few years ago when Cal Trans showed up with drawings for a 50 percent wider 101. They planned to add a dozen-plus acres of pavement to the sprawling highway that since the ’60s has disfigured Summerland, sundering our shoreline from us, along with a grounded sense of place.

With more work and wrestling than I care to remember, a small team of champions fought to capture what we could of our town’s soul though the addition of local design elements to the state’s plans. We nearly failed and were only partially successful, but were able to add some native character to the proposed tons of concrete and highway paving madness again coming our way.

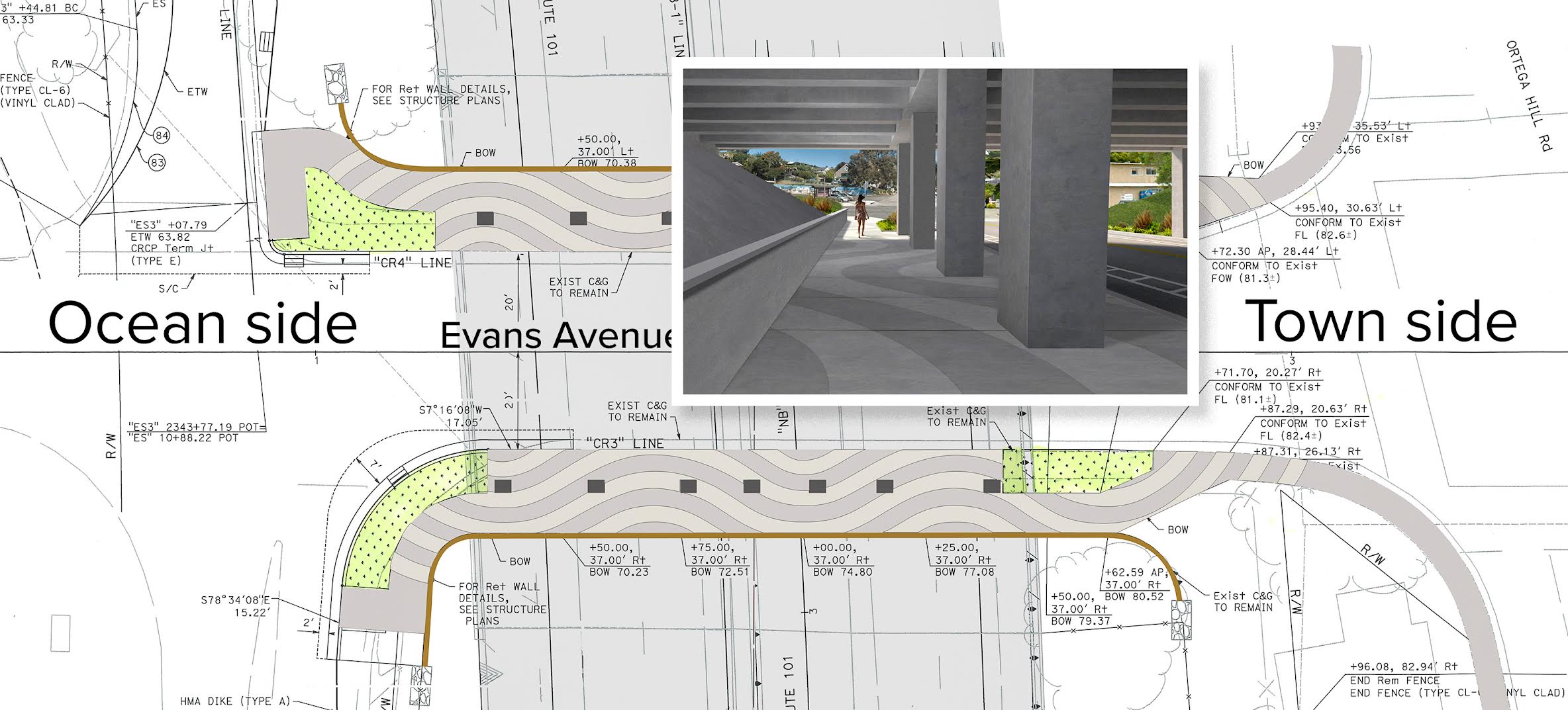

Only one skinny, central tunnel penetrates mighty 101–the Evans Avenue undercrossing. That solitary tube is key to holding together our split Summerland, connecting homes and businesses with nature and recreation, and a sense of place with place. During planning meetings with the state, county and buttinskies, we were told that the undercrossing must look like other highway structures up and downcoast that were to be remodeled or rebuilt. The planners sought a “continuity of commuter experience” and a certain “Santa Barbara look.” Some of us felt we deserved more than that for the edifice that dominates our center. One that was attuned to Summerland, distinctive, delightful, and memorable. One that announced SUMMERLAND. And because the undercrossing needed only strengthening, not razing, our opportunity was limited.

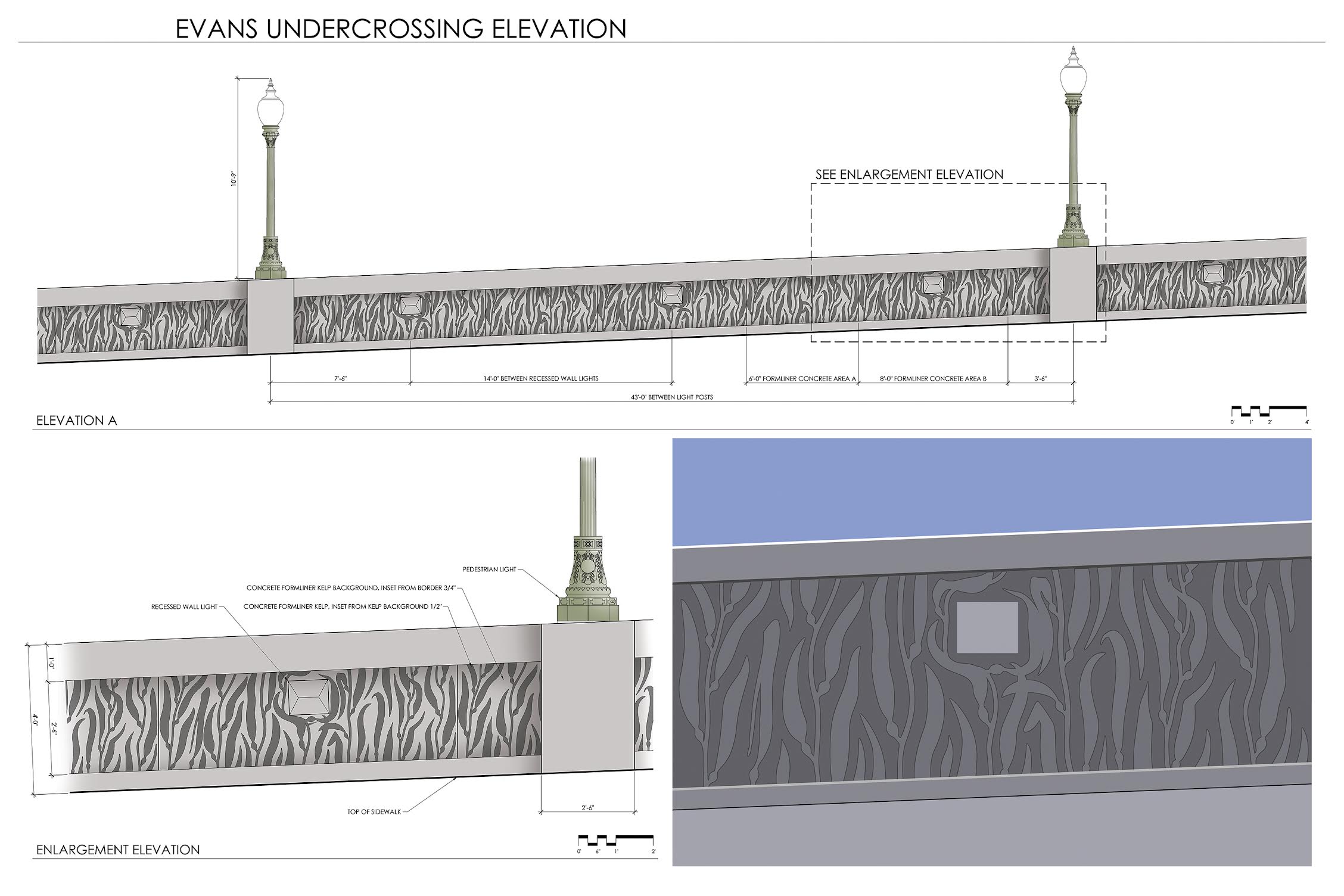

Construction is underway. Falsework is up. Formboards are built. Soon the community’s own sun designs will dress up the old, cold Evans undercrossing to celebrate the warmth enjoyed here on Summerland’s uncommon, nearshore, south-facing hillsides. The Summerland name and founding date will be stamped into a new fascia above the undercrossing’s entrances to say this is SUMMERLAND, a unique and separate place. Pedestrians will enjoy wavey patterned new sidewalks that will lyrically reflect location and animate the undercrossing’s passageways. The tired, 60s look of highway buttresses when Evans was built will be textured with an eclectic, board detail reminiscent of Summerland’s early wharfs and built environment. New interior lamps and columns will be more anonymous and less distinguished than we hoped. But on long, new sidewalk retaining walls, a deeply cast, joyful pattern of kelp will celebrate Summerland’s pioneering past, seaside setting and spirit.

Too much of the local team’s vision–homey features like a tiny community plaza; public art sites; tailored columns and highway center divider; and fun, indigenous colors and lighting–got lost in a too painful effort to encourage indifferent overseers to give back a little of Summerland. But in limited, though significant, details, we will soon enjoy a greater sense of place–a greater sense of OUR exceptional place. And, for me, these community-made designs will be an enduring reminder of the challenging and rewarding work of mindful citizens who shared a vision.

You must be logged in to post a comment.