Parents Fight to Keep Mentally Ill Son Off the Streets and Out of Jail

Everett Beeman’s Father Says ‘System Is Stacked Against Families in Need’

The drive from San Francisco was going pleasantly enough with Monica Quirarte-Beeman behind the wheel and her 29-year-old son, Everett, happy to be heading home for the holidays. They listened to music and chatted. Monica tried keeping it light.

It had been a difficult year for Everett. He’d been dropped by his graduate program and separated from his partner, and he was living alone, struggling with the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that had plagued him since junior high school. He was having trouble sleeping. Sometimes he heard voices.

As they entered Goleta on the way to their home in Ventura, Everett became worried they were being followed by the police. Monica assured him they were not. He didn’t believe her. His hands clenched, and his paranoia turned toward her. He accused her of conspiring against him. She tried changing the subject and defusing the tension. Suddenly, he hit her in the arm.

Monica turned off the highway and pulled into an apartment complex, where things escalated. Everett struck her harder, this time in the back of the head. He gouged her eye and tried to snatch her cell phone. Overhearing the commotion, an off-duty Santa Barbara County firefighter intervened, and Sheriff’s deputies arrived soon after. “It was just shocking to me,” said Monica. “He had never been violent like that before.”

The deputies encouraged Monica to press charges, not for punitive reasons, but so Everett could be enrolled in the county’s Mental Health Court and receive the psychiatric services he needed. They promised him help. Monica was hesitant. “I was adamant that he not just be shipped to jail,” she said. “It would be so counterproductive to put him in a place where he couldn’t get his medication and that might not acknowledge his mental illness.”

But, after years of failed attempts to stabilize Everett at expensive private facilities, Monica ultimately agreed, and Everett was taken into custody, where he spent Christmas and New Year’s and began a downward spiral from which he has yet to recover.

Over the past year, as Everett has cycled in and out of jails in Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and Ventura, his family has continued to advocate on his behalf, thankful for individuals who have lent a hand along the way but frustrated by court-ordered diversion programs that sometimes promise more than they can deliver. Especially for those whose legal issues cross county lines.

“Everett has problems, and I’m not trying to excuse his behavior,” said his father, Randal. “But the system is stacked against families in need.” Their situation is hardly unique, he explained. “It’s a story that’s being replayed all over.”

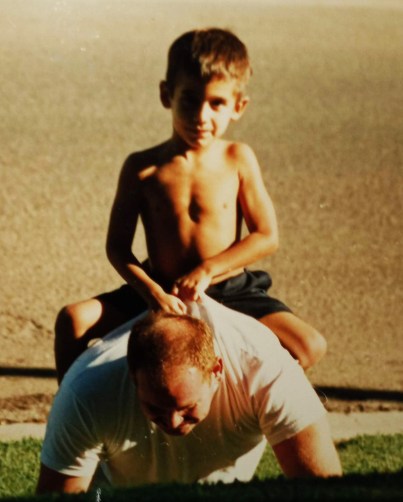

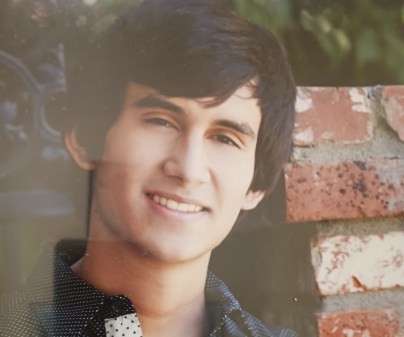

Everett Beeman grew up in Bakersfield, the middle of three brothers. He excelled in parochial school and would be disappointed in himself if his grades ever fell below an A. Achievement runs in the family ― Randal is a history professor who recently taught at Westmont College, Monica works with children with autism, and one of Everett’s brothers went to UCSB and now has his PhD. The other is a robotics engineer for Amazon.

In junior high, Everett came out as gay. He was bullied by some of his peers, though his parents didn’t know it at the time. They did, however, begin to notice an overall change in his behavior. It became less predictable. His friends started pulling away. Everett transferred to a public school, where he seemed more content, and was later accepted to UC Irvine.

All was well for a while. Everett made new friends and enjoyed dorm life. But after about a year, his growing mental health struggles overwhelmed him. By the time Randal and Monica picked him up and brought him home, his weight had dropped to 135 pounds and his teeth were riddled with cavities. His backpack was half-filled with the various medications he’d been prescribed.

In and out of treatment facilities, Everett ultimately found his footing again and was reaccepted to Irvine. To the relief of everyone, he graduated, and he began pursuing a master’s degree in philosophy at San Francisco State University. It wasn’t long, however, before he really started to unravel. His weight ballooned up to 300 pounds. He fought with his boyfriend. And he began hallucinating.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Again, Everett’s parents did what they could to help, and Monica drove north to shuttle him once more back home. It was on this trip that the attack took place. As the deputies had promised, Everett was assigned to Santa Barbara County’s Mental Health Court, where a prison sentence for felony assault was suspended in favor of gentler interventions, like mandated therapy, anger management, medication, and the assignment of a social worker to his case.

Randal claims, however, that these services were too slow in reaching Everett, who resented Monica for pressing charges, which included a restraining order. He quickly returned to San Francisco. On his own, he was soon in trouble again and locked up, this time for four months, for threatening his neighbors.

Once his San Francisco sentence was completed, he was transferred back to Santa Barbara’s custody, where attempts at diversion continued. He was sent to a LGBTQ-friendly facility in Los Angeles that, according to Randal, was not equipped to handle Everett’s acute mental health needs. Everett wound up walking away from the center and roaming the streets of L.A. with no shoes, coat, or money. It started to rain. A bank employee took pity on him when he tried withdrawing the last $4.24 from his account, giving him $20 and letting him use her cell phone.

Everett called his parents, and Randal sent an Uber to bring him home. Randal said he received assurances from the Santa Barbara County Probation Department that Monica’s restraining order had been amended to allow contact with the two of them. When Everett walked through the front door, Randal was relieved and elated. It had been a year since he’d been able to hug him. “I was so happy to see my son,” he said. “He was remarkably cogent, but he wasn’t on his meds.”

The next day, after a shower and a few square meals, Randal and Monica tried to convince Everett to visit the emergency room so he could quickly get back on his medications. Everett resisted. He became upset. Fearing the situation could spiral out of control, Randal called the police to help him and Monica escort Everett to the ER. But when the officers arrived, they said the prior restraining order was still active and they would have to take Everett into custody. Randal pleaded with them not to. The officers said their hands were tied.

At the Ventura County Jail, Everett’s anger and paranoia only grew and eventually exploded into a fight with two guards. One of them sustained a cut above his lip that was treated with an ice pack and ibuprofen. Everett received two black eyes. He was charged with felony assault on a peace officer with a recommendation from prosecutors that he be sentenced to six more months. Randal and Monica worried that both of their attempts to solicit law enforcement’s help in their son’s mental health difficulties had only made things worse.

When the Independent recently tried to speak with Everett at the Ventura jail, where he’d been placed in an isolation cell, officials said he was too agitated to take visitors. Randal said he was becoming more of a feral animal than a human being. Attempts to reach him by phone were also unsuccessful. Everett later told Randal he didn’t trust anyone from Santa Barbara and that reporters were likely working with the police.

It was the quick work of a Ventura County public defender that got the charges against Everett dropped last week and allowed him to be released from custody. By contrast, Randal said, working with Santa Barbara public defenders has been a “fiasco.” Phone calls are rarely answered, he complained, and voicemail boxes are almost always full. Similarly, the Ventura judge voiced exasperation that the Santa Barbara restraining order confusion had landed Everett behind bars in the first place. If not for that error, he said, the fight with the guards wouldn’t have occurred.

Even though Everett is out of jail, Randal explained, he is hardly out of the woods. He continues to resist treatment and is more “sad, confused, and angry than ever before.” More than once he’s wandered back onto the streets. “He said he prefers being homeless than accepting more ‘help’ from the government, who he thinks is trying to kill him,” Randal said. Ironically, it is that lack of a permanent residence that may be the biggest impediment to securing meaningful assistance for Everett, as California counties have a notoriously difficult time coordinating with one another in such cases.

Randal and Monica said they’ll continue to do everything they can to ensure Everett receives the treatment and support he needs. “We have no problem putting every dime we own into our child,” said Randal, noting their savings are nearly exhausted. “But at this point, we need the system to help us.” They continue to do their own research on options for inpatient treatment and a potential conservatorship. They have been especially thankful for the information and resources they’ve gleaned from NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Beyond Everett’s case, Randal wants to start advocating for others in similar straits. “I am going to get more involved in educating people about how well-meaning programs need budgets, staff, and most of all, accountability,” he declared. At the very least, he hopes telling their story will make other families feel less alone. “If this is happening to us, I can only imagine what it’s like for people who can’t speak up,” he said.

Longer term, Randal hopes Everett can realize his desire to one day support those who share the same demons, perhaps by combining his personal experiences with his interest in philosophy. “He wants to be normal,” said Randal. “He wants to function.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.