Every Child Deserves to Play

Gwendolyn's Playground Will Be the First in Santa Barbara for All Children

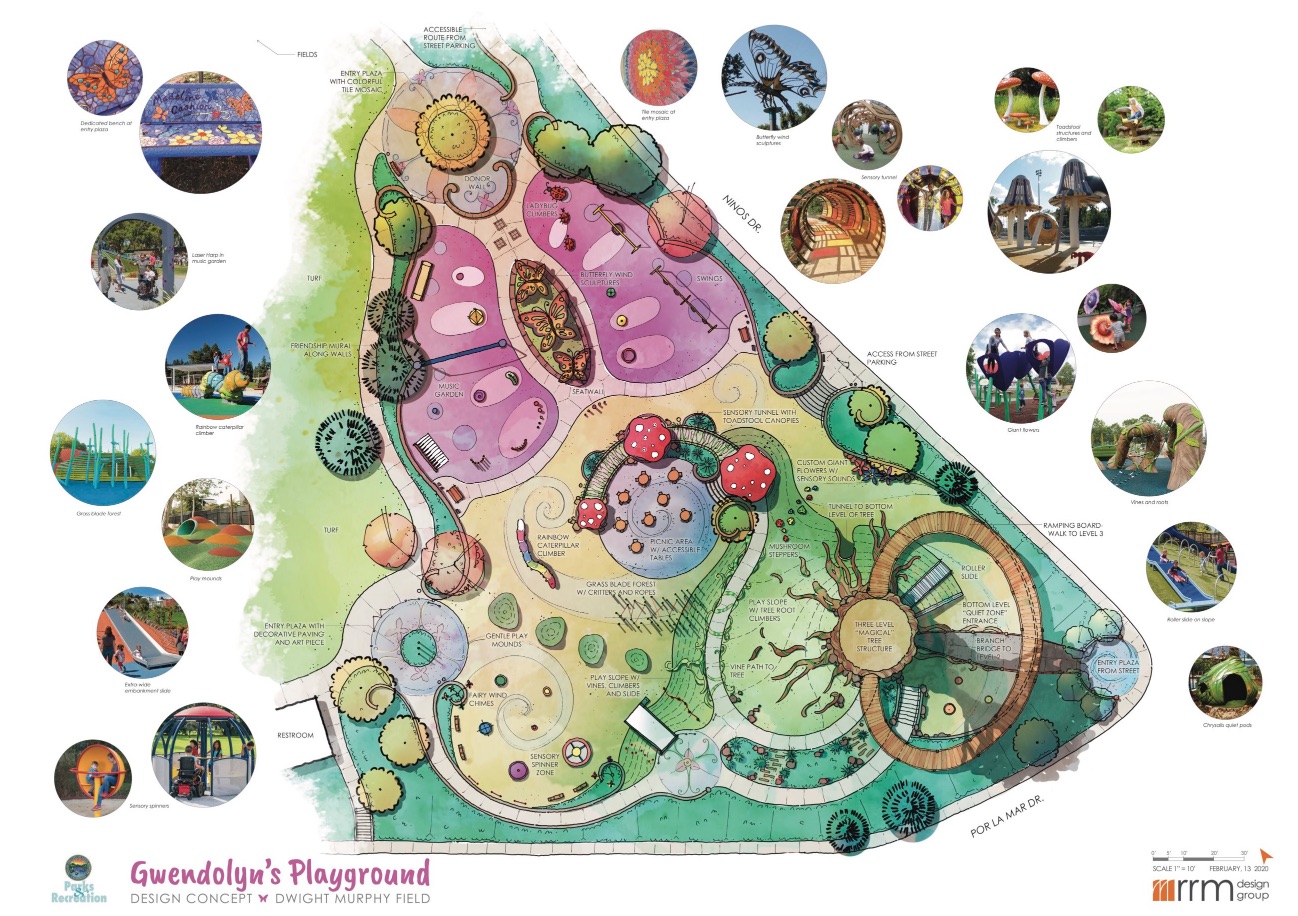

This year’s Butterfly Ball fundraiser for Gwendolyn’s Playground for children of all abilities and disabilities put the fundraising effort across the $5 million mark. The fully inclusive playground has another $1 million to go to reach the $6 million it will take to buid the playground, and its supporters intend to raise another $3 million for the baseball and multi-sport field at Dwight Murphy Field. Analise Maggio’s heartfelt speech at the Butterfly Ball explains the importance of this goal.

I met the Strongs in early 2011, just after Gwendolyn’s third birthday. We had moved to a new home on Laguna Street, and the Strongs lived around the corner. I had a newborn baby boy, my first, and I was rocking him in a rocking chair on our front porch one day when Bill and Gwendolyn walked by. I still remember seeing Gwendolyn for the first time, lying flat in a wheelchair with breathing tubes and machines traveling with her. I was an exhausted new mother. My son was just weeks old and he didn’t sleep much, and I was so tired. And while I was wallowing in my exhaustion, here were Bill and Gwendolyn, delighting in their time together, grateful to be outside, counting their blessings. “What am I complaining about?” I thought. Life must be so different for them.

I had already heard about the Strongs and the foundation they started in their daughter’s name: the Gwendolyn Strong Foundation. Gwendolyn was born with a rare genetic disease called spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, for which there was no treatment. She was perfectly healthy at birth, but by three months old she was having a hard time holding her head up, and by the time she was one, Gwendolyn was completely paralyzed. Her mother, Victoria, wrote a blog chronicling life with Gwendolyn. I read every word. She courageously and honestly described the challenges their family faced every day, the work they were doing, the gifts Gwendolyn gave them. Here was this fellow mama doing everything she could for her baby girl. And I thought, we are so alike. I would do anything for my child, too.

This is one of the first lessons I learned from the Strongs: sometimes a profound difference is the first thing we see. But the more we share with each other, the more we realize how much we have in common, how much we are the same after all.

Gwendolyn’s cognitive ability was completely intact, and she communicated with her eyes and her fingers. When I smiled at her and said hello, her eyes would light up, her fingers would tap. This beautiful little girl, with a body that defied her, was so full of spirit and life.

By age 4, Gwendolyn was reading. And by then, the Gwendolyn Strong foundation had funded 200 specially designed ipads that were delivered to kids with SMA, so that they could now communicate in ways they had never been able before.

Gwendolyn started kindergarten at Washington Elementary. She loved it. Victoria wrote about Gwendolyn’s friendships, her social butterfly personality, and how much she felt that she belonged.

In the first grade, Gwendolyn’s self-portrait depicted her long hair, her butterfly bow, her breathing tube, and a simple statement, “I am happy.”

Just before her 8th birthday, we lost Gwendolyn to SMA. I wore a gold and purple dress to the Celebration of Gwendolyn’s Life. Victoria asked us to dress in bright colors and butterflies. It is what Gwendolyn would have wanted.

Four months after Gwendolyn passed away, the FDA approved a treatment largely funded by The Gwendolyn Strong Foundation that, if administered at birth, would prevent all symptoms of SMA in a child carrying the gene. Effectively, four months after we lost Gwendolyn, we found a cure. And we celebrated the win, while we mourned the loss of our Gwendolyn.

And surely, this was all enough. The Strongs, in tandem with their staggering loss, had already made the world so much better.

But there was something else that needed fixing.

It would be years after I first met them, that I learned that the reason we saw Gwendolyn and Bill walking by our house on Laguna Street so often, was because if they didn’t turn down our street, they would arrive at Kids’ World, a big, popular playground downtown. And Gwendolyn would beg to play, her eyes and fingers pleading. And Bill would have to explain that she, and the equipment that quite literally kept her alive, couldn’t traverse the playground’s wood chip flooring and climbing structures.

So Gwendolyn didn’t get to play with our children at Kids’ World. And much more detrimental, in my opinion: our children didn’t get to play with Gwendolyn.

Playgrounds are our first community, our common ground, where differences fall away and we revel in the freedom of play. They stoke our imaginations and teach us that anything is possible. We learn to share, to take turns, to wish for others to experience the same joy we feel. We carry these life skills into adulthood. But if we’re not all there together – if we’re not sharing that magical space with children of all abilities and disabilities, then we’re limiting our life skills to only understanding those who are just like us. And the world is much bigger than that.

As they have always done, the Strongs boldly confronted this challenge, too: if Santa Barbara doesn’t have a playground where ALL of our children can play, then we will build one. And it will be big, and beautiful, with bright colors and butterflies … it is what Gwendolyn would have wanted.

After Victoria invited me to join the Playground board, after years of friendship, we discovered something that stunned us: Victoria’s mother and my father were born and raised in the same small town in Mississippi. They both eventually made their way to California, and both had daughters, born just three weeks apart: Victoria, and me.

Victoria and I grew up spending our summers with grandparents in the same small town in Mississippi. When we realized this, Victoria looked at me and said, “Analise, I think we played on the same playground.”

I instantly pictured Vicksburg, Mississippi. The swing set at the firehouse, the big blocks down by the river where children play, and two little girls, from different places, playing together, possibly imagining this moment: where an entire community comes together and builds a playground where ALL of our children can play.

You must be logged in to post a comment.