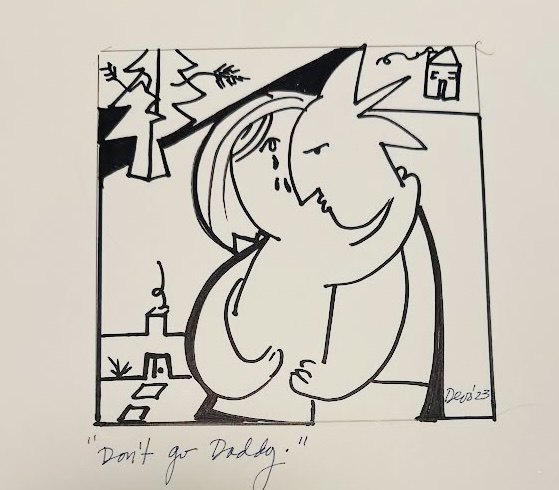

A Crooked Christmas Tree Straightens Out

How a Tree Saved My Relationship with My Dad

The first Christmas after my parents divorced is a blur. Trauma gets tucked away as a child, and time thankfully washes it away like a sponge on a blackboard. I do recall I had managed to convince the new school I was going to, to let me skip the second half of fifth grade. It meant I would never get a good grip on World History and Geography.

Genghis Who? His last name is Cohen, he was a Jew right? Having been to China I learned otherwise.

At Dad’s house we celebrated Hanukkah, but without Dad around, it did not happen. My sisters and I tried crafting a miniature menorah with Play-Doh using tiny birthday candles to keep the tradition alive. But our Play-Doh menorah could not hold a candle really, compared to our great grandmother’s pre-WWII solid brass menorah from Kovno, Lithuania with its beautiful tapered, slow burning candles. Eight presents, one for each night, now just forget about it. Everything was green or red with reindeers or with Santa wrapping in boxes and an angel smiled from the top limb, instead of Dad’s six-pointed star he’d put up there on our last Hanakamus.

And If you look at the Kodak color photos of myself and my two sisters, posing around the Christmas tree, in our new velveteen matching sweaters, with unwrapped presents under the colored lights — we girls look worse than miserable. But I am not here to kvetch. Thankfully, Mom and Dad were respectful and continued to keep the peace between them. I suppose for many families that is not the case. I heard tales of much worse pre- and post-divorce from my new friends.

Nevertheless, I knew that if I was shocked at the sudden change in our family dynamic, Dad must really be feeling it. We had no idea that anything was going down until it did. Dad pulled us into his study, said we were moving and then we found out — but without him. As he excused us and made us promise not to tell our baby sister just yet, I could hear him push back his chair and his voice was uncharacteristically hoarse. “But you can always come visit.”

And sure enough, the feelings bubbling, under the calm that I imagined my Dad was feeling, were well-masked. I’d catch his look in the rear-view mirror dropping us off after a day with him — his tense smile as he said goodbye with his cracking voice. Years later I would learn that for him it was the most devastating time of his life.

Even though there was no visible evidence of his sadness, I must have felt something when he drove us past DeLancy’s Christmas Tree lot one December Sunday. We all used to go the night before Christmas to get a deal on whatever trees were left over. Then we’d stay up late and fall asleep waiting for Santa to show up as Mom and Dad decorated the tree and put the presents around. Of course, like every bored kid when it comes to decorating, we’d fall asleep on the couch, and have to be carried to bed. Then we girls would wake up early in the hopes of catching Santa.

That second Christmas, seeing my Dad’s mood, I had to do something. Something that I felt would cheer him up. On my way back bicycling from my art class, I saw a Christmas tree lot. It was not the one we used to go to. Zipping past on my Raleigh bicycle, I came to a grinding halt. Outside was one lonely, very small, scraggly but live Christmas Tree. Smaller than me and in a pot. A live tree! I raced home, poured out the contents of my piggy bank, circa 1963, and peddled back. Getting there I convinced the Christmas tree lot guy to sell me the tree for half-price. After all, I was only half as tall as an adult.

I gave the tree to my Dad, who promptly planted it in the yard. It began to grow. Between the summer when I graduated elementary school and my first year in high school I grew four inches. So did the tree.

Would there be a problem with my bones growing so fast? What about the Christmas tree?

When I visited Dad, I would talk to my Christmas tree gift. Dad assured me he was taking good care of it. After all, he is a doctor and living things were important to him. For instance, he was understanding, but not happy, when I accidentally killed my collected polliwogs, when I dug a pond under the tree but did not want to wait for the cement to dry. A child’s mistake but devastating nonetheless, to this day.

As I grew, the tree grew. When Dad moved a couple blocks away he dug up the tree, now five-feet-tall and put it in the front yard of his new house where it could grow unobstructed.

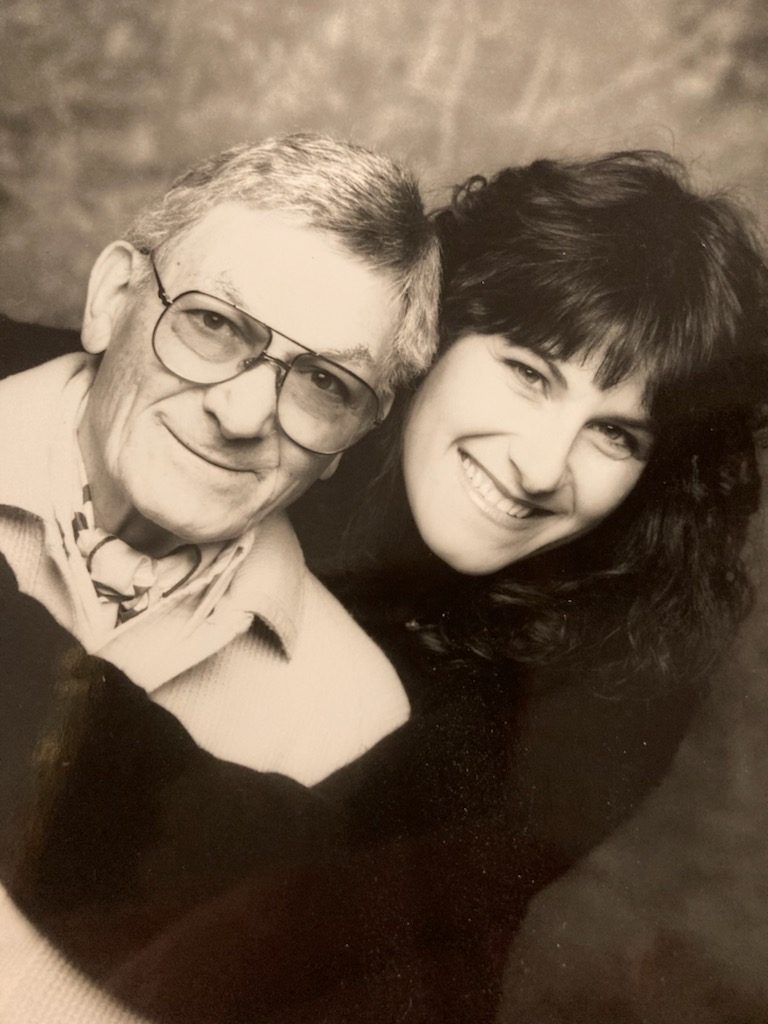

Something happened to the tree. It was on a small hill, and it started to grow crooked. But by college the tree had straightened out and at my graduation, and after I’d gotten my first job at the studio, Dad proudly admitted that he had been a bit worried about me and the tree, but we had both straightened out over time.

I think about all the holiday times families are sharing now, rushing about to prepare for the moment where they can all sit and relax with each other, enjoy a meal despite whatever feuding, arguments, or conflict had happened that year. It could be a time of reflection, reconciliation, or just the recognition we are family.

Many Christmases later I was excited, in my early 20s, to be in-charge of preparing the turkey for our holiday meal at Dad’s house. Then a surly guest walked into “my kitchen,” with a half-cooked turkey in a bake pan. She sashayed towards me and pushed me and my little checkered apron aside. Wow, I thought, who is this person? She proceeded to put her own turkey in the oven and took mine out of the oven to make room for hers. I had a kind of breakdown. I guess she’d heard it was my first holiday meal and took over. I walked upstairs in a daze, without saying a word, and laid down in my Dad’s bed. After about an hour, he found me and said, “It’s okay. You do not have to say anything. We miss you downstairs, but I get it. I’ll save you some turkey.”

I was frozen in shock and grief and thinking about it now, maybe it was a kind of emotional jetlag, a trigger memory long forgotten of losing control of our family unit.

Something inside me forced me out of my cave and I grabbed Dad’s arm and said, “Not hers, Dad… Can you put mine back in the oven if it’s not too late?” He nodded. Then I asked, “Why would she do that?”

He thought for a brief moment then said “I do not know. She is kind of a controlling person. And she does not trust people. She’s unhappy.”

“Dad, I bet you are right,” I said. Then he pointed to the window, where the tree he had planted, the one I had given him years ago, was scratching at the window as if it were some kind of tree morse code. It was tall enough now to reach our roof and was sticking its pine needles through the second story open window. “That’s ours and we at least know the most important thing.”

“What’s that Dad?” I asked, feeling a tad better.

“You straightened out. You’ll be okay, just rest,” Dad said as he pulled the covers up over me. He kissed my forehead.

“I love you,” he said. “Thanks for the tree, I am not sure I ever properly thanked you.”

As he left and slid the door shut, I wished I said, “Dad, thanks for loving me, just as I am. Thanks for trusting that the tree that is me would straighten out.”

Premier Events

Sat, May 04

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In-Person and Online Talk: “Scientific Foundations of Musical Expression”

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

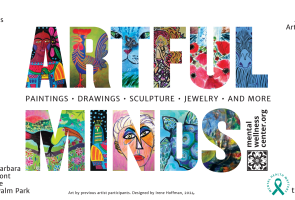

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04

3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Treble Clef Women’s Chorus Spring Concert and Reception

Sat, May 04

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

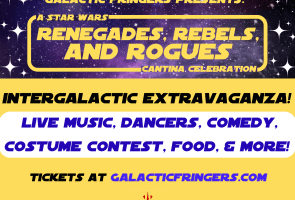

A Star Wars Cantina Celebration: Renegades, Rebels, and Rogues

Tue, May 07

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

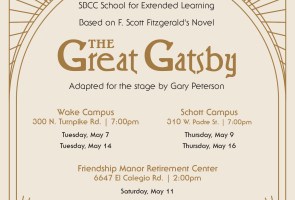

Theatre Eclectic Presents “The Great Gatsby” – Wake Auditorium

Thu, May 09

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Friendship Center’s Mother’s Day Celebration

Thu, May 09

7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mother’s Day Weekend at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In-Person and Online Talk: “Scientific Foundations of Musical Expression”

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04 3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Treble Clef Women’s Chorus Spring Concert and Reception

Sat, May 04 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

A Star Wars Cantina Celebration: Renegades, Rebels, and Rogues

Tue, May 07 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Theatre Eclectic Presents “The Great Gatsby” – Wake Auditorium

Thu, May 09 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Friendship Center’s Mother’s Day Celebration

Thu, May 09 7:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

San Marcos High School Theater Presents, “Singin’ in the Rain”

Fri, May 10 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.