Santa Barbara County Supervisors Wrestle Greased Pig of Cannabis Taxation; Greased Pig Wins

Growers and Operators Unite in Opposition to Newly Proposed Tax Scheme Based on Square Footage

Cannabis may not have become quite the cash cow envisioned back in June 2018 when voters statewide voted to legalize commercial cultivation for recreational use, but the Santa Barbara County supervisors were reminded last Tuesday afternoon that when it comes to actually collecting taxes, the cannabis industry has become a greased pig that few could have imagined.

Efforts to wrestle that pig into submission have proved vexing and challenging, as the county Board of Supervisors discovered again last Tuesday. That’s when they were informed there are no quick fixes or easy solutions when it comes to devising new taxation approaches that are less susceptible to industry evasion and that don’t also kill the proverbial goose that lays the equally proverbial golden egg.

The stakes involved are undeniably high. In the past five years, commercial cannabis has generated $50 million in gross revenues for the County of Santa Barbara. For the most recent quarter, that number is $2.3 million. While the cannabis industry has tanked the past two years due to massive glut on the market, the supervisors were told Santa Barbara County has collected the most cannabis-infused tax revenues of any county in the state. Santa Barbara County, they were also told, also happens to have the most land under legal cultivation in the state.

How much of that $50 million is “net” — above and beyond the costs of administration and enforcement for an industry that’s inflicted massive growing pains on itself and the community at large — however, is not certain. But the industry is now reportedly coming out of its tailspin, so the upside to the county in terms of additional tax revenues is of more than merely theoretical interest.

For the past two years, county tax administrators have been giving serious thought to changing the ways cannabis growers are taxed; the current system — which taxes operators based on the gross receipts they choose to self-report — has been fraught with problems. Some operators, it turned out, simply did not submit reports; some claimed no taxable revenue; often the reports were submitted late.

Others, the supervisors have only recently discovered, have reportedly gamed legal loopholes in the system that allow operators to significantly undervalue the cash value of their crop. This, they do, by selling their own product to themselves at artificially low prices and then filing tax payments based on those artificially low values.

Even for operators who comply, county tax collectors have been forced to rely on the accuracy of their numbers; independent verification has been problematic and time-consuming. Attempting to keep tabs on this new and challenging industry have been two full-time county tax collectors.

Many supervisors have argued that the solution lay in taxing cultivators and operators based on the square footage of their licensed space instead. This had the virtue of being administratively simple, a one-size-fits-all solution that was easy to independently verify and did not rely upon the honesty or accuracy of the operators. It would be transparent and easy to administer and would presumably inoculate the county from the manic variations of the boom-bust market volatility that’s characterized the industry to date. The market highs may not be so high, but the lows would not be so low either; under this scheme, cannabis revenue streams would be — it was believed — more reliable and predictable.

On Tuesday, the supervisors were disabused of any such optimism. Counties that have relied on a square foot system, they heard, were either shifting to a gross revenue model, cutting taxes by 90 percent or declaring an all-out tax holiday to help keep an ailing industry afloat.

What would be a tax rate that was both fair to the industry but remunerative to the county? How much more would the county tax cannabis grown in greenhouses as opposed to in large open fields? Some cannabis is grown for flowers on the lucrative high-end market. Other cannabis is grown to be mowed down and converted into oils. Presumably there would be a tax differential between the two, but if so, for how much? The devil, the supervisors were told, lay in such details. And what those details are remain to be determined.

The person most knowledgeable about the cash flow and finances of the still-emergent cannabis industry is Treasurer-Tax Collector Harry Hagen, but Hagen was out of town on a business trip to Las Vegas. As such, he was not on hand to brief the board on what he’s learned since launching an extensive audit of several key operators. The objective is to figure out tax rates that won’t kill the industry but don’t leave skin on the table from the county’s perspective as a tax collector.

Supervisor Bob Nelson wanted a new tax system, but according to weight rather than square footage. He dismissed the virtues of the square footage approach, saying that one half of growers would pay less, the other half would pay more. It would be, he said, a wash.

But even under weight, there were questions. Would you tax based on the weight of freshly picked cannabis or the weight after the cannabis has been dried? What was the sweet spot that would allow the county to recoup more of the benefits the new industry has to offer without putting it out of business? Supervisor Laura Capps wanted to know how much less staff time would be needed under the square footage approach.

The growers and operators appeared united in their opposition to the new tax scheme. One Carpinteria grower — David Van Wingerden — said the new approach would add $100,000 to his costs a year. An attorney for the industry, Amy Steinfeld, argued the square foot approach was not sensitive enough to price fluctuations. One grower said the additional costs incurred by a new system would prompt growers to plant an additional harvest, thus adding to any odor issues. A Cuyama operator complained he had to spend $1 million already just to secure a key planning permit; to add to his tax burden, he said, would be destructive to the industry. Another grower urged the supervisors to give greater consideration to the number of well-paying jobs the industry is providing when contemplating what change — if any — they might seek.

Some problems, it turns out, can be fixed relatively simply and administratively, like the loophole that allows growers to sell their own cannabis to themselves. But should the supervisors opt to tax cannabis according to square footage instead of gross receipts, this would have to be approved by a vote of the people.

That’s because the existing tax scheme — specifying what tax rate would be charged and for which cannabis products — was baked into the county’s ordinance language by a popular vote in the county ballot of June 2018. Only by another vote of the people can that language be legally changed. To place any proposed changes on the ballot, the supervisors will need a special four-vote supermajority. At this stage, it’s too soon to say whether the supervisors can craft something that can cross that hurdle.

The supervisors will revisit the matter in mid-May; presumably by then, there will be some real numbers on the table. As of this writing, it’s unclear if a four-vote supermajority is even possible. To qualify anything for the November ballot, the language would have to be adopted no later than this June.

Premier Events

Sun, Apr 28

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

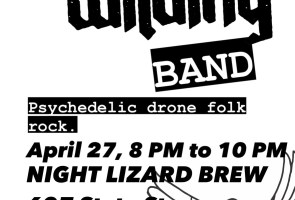

Sat, Apr 27

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

Sat, Apr 27

3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

Sat, Apr 27

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03

8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

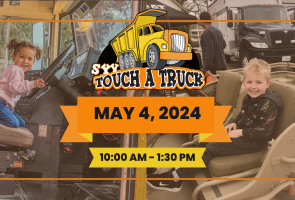

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sun, Apr 28 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Sat, Apr 27 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

Sat, Apr 27 3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

Sat, Apr 27 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03 8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang