‘Do Something,’ Santa Barbara Sheriff Challenges Board of Supervisors

‘We Already Have,’ Board Replies During Heated Budget Workshop

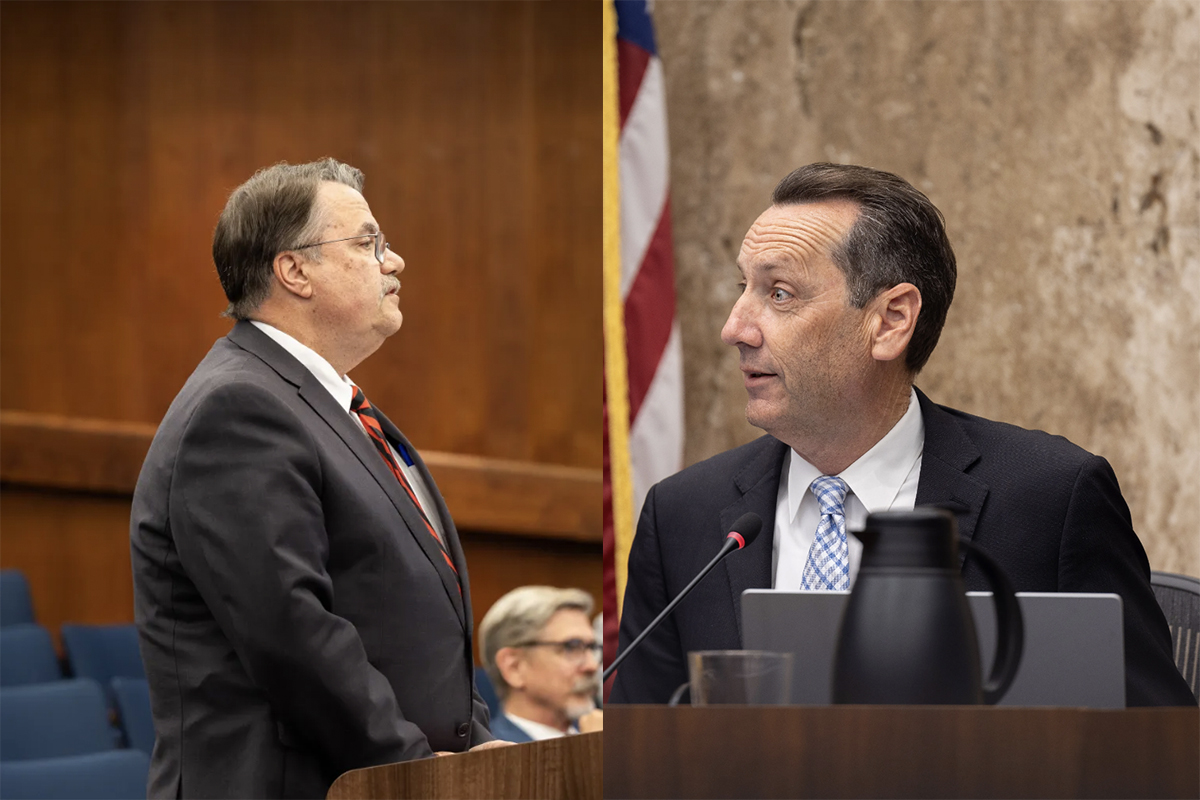

It promises to be a long, bumpy spring for Santa Barbara Sheriff Bill Brown, who for the second week in a row came away with a lot of “no”s in response to his request for more money from the county Board of Supervisors to fight the ravages of fentanyl and other drug overdoses.

“You need to do something,” an insistent Brown exhorted the county supervisors. Just as insistently, one of the supervisors replied that they already had and would like some acknowledgement, while others questioned whether the solution Brown proposed — approving the creation of a second five-person crew of narcotics investigators — was the most effective response.

Voted into office in 2006, Brown is one of the few elected officials in the county able to be somber and agitated in the same breath. Last week, he told the supervisors that 226 county residents died of drug overdoses last year. Just last week, he said this Tuesday, another three had died. In March, he noted, a 14-year-old junior high school student from Santa Maria had overdosed. Driving these numbers is the arrival of fentanyl on the scene, infamously deadly in even the smallest of doses.

Brown’s timing could not have been worse. Tuesday was the first of this week’s county budget workshops; the edict from County Executive Officer Mona Miyasato is that this year there will be no funding increases or cuts in services. Brown is asking for a bump of $2.8 million over what his department got last year. Some of that would be used to field the five additional narcotics investigators he is seeking. (Currently, there are only five full-time narcotics investigators in all Santa Barbara’s law enforcement agencies.)

“When you say, ‘You have to do something,’ it’s frustrating for me,” said Supervisor Steve Lavagnino of Santa Maria. What about the $40 million the supervisors squirrelled away to build the new Northern Branch Jail, he asked, or the $23 million to fix up the Main Jail or the $10 million to make a civil rights lawsuit against that jail go away? “At some point, there has to be a realization from your department that there’s not a grove of money trees in our backyard.” When Brown replied he was grateful for the support, Lavagnino shot back he didn’t want gratitude; he wanted acknowledgement.

Adding to the supervisors’ ire was Brown’s argument they needed to restore the 50 sworn positions that disappeared after the recession of 2007. Supervisor Bob Nelson said he had “heartburn” enough already that Brown currently has 107 vacant-but-funded positions in his department. With Brown’s chronic problems in recruiting and retaining sworn personnel — a national and statewide problem afflicting all law enforcement agencies — supervisors questioned the wisdom of adding more positions to the budget. Brown said such a gesture would go a long way to improving morale among his troops.

More broadly, this showdown comes on the heels of three arduous years of a broader criminal justice reform effort, the subject of much discussion this past Tuesday by the supervisors and the most immediately involved department heads — District Attorney John Savrnoch, Public Defender Tracy Macuga, and Chief Probation Officer Holly Benton. Though some supervisors may disagree on details, all have endorsed the thrust of this diversion-focused reform, which has been quietly but forcefully championed by Miyasato.

In other words, it’s a stiff political wind into which Brown, now head of the Major County Sheriffs of America, finds himself confronting. Brown did not back down from his demand for the additional narcotics investigators, describing the spike in overdose deaths as “an exigent circumstance” justifying a breach of budget protocol. “It’s the only one of our problems where people are dying now.”

Supervisor Joan Hartmann noted there’d been a drop in overdose deaths in the past two years among those ages 18-34, while the biggest spike has afflicted white males ages 35-55. Clearly younger drug users were getting the memo, Hartmann suggested. How did Brown intend to reach the older white males? She also noted that 70 percent of the deaths in a six-month period involved people who’d previously spent time in county jail. Jail prevention and intervention, she suggested, was the obvious place to focus.

Miyasato will use the discussion from the budget workshops to put together her final-draft budget by May 1. The supervisors then have until June 30 to pass one they like. “Buckle up and drive carefully,” Miyasato said Tuesday, channeling her inner Bette Davis. “It’s going to be a bumpy year.”

Premier Events

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Wed, May 01

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03

8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

Sat, May 04

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04

3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

A Star Wars Cantina Celebration: Renegades, Rebels, and Rogues

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Wed, May 01 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03 8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mental Wellness Center’s 28th Annual Arts Faire

Sat, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Community History Day

Sat, May 04 3:00 PM

Solvang

The SYV Chorale Presents Disney Magic Concert

Sat, May 04 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara