Last year, the Michelin Guide announced that it would be turning its attention to the world of wine, with plans to rate wineries around the world on a one-to-three-grape scale. This mirrors the three-star rating system that the tire company launched in 1926 to lure people onto the roads and into the restaurants of France, which rose over the decades to become the world’s most exalted restaurant review platform.

There was little surprise that Michelin was interested in wine, given that the company bought The Wine Advocate in 2019. That was the same year that the Guide started evaluating Central Coast restaurants in 2019, giving Santa Barbara County our first stars two years later, with Bell’s in Los Alamos and Sushi | Bar in Montecito making the one-star grade. Since then, Caruso’s and Silvers Omakase joined the one-star club with Bell’s, while Sushi | Bar is no longer on that list. There are also another 20 or so Santa Barbara restaurants listed by the Guide under lesser designations.

In last fall’s announcement, the Michelin Guide explained that its team of behind-the-scenes-but-not-anonymous experts would be reviewing wineries based on five criteria that range from farming and winemaking techniques to the quality of the finished wines. The first regions to be evaluated will be Burgundy and Bordeaux, and it remains unclear when the Guide will reach California, though the odds favor Napa Valley being first.

Despite the somewhat vague plans about the process and the future regions, winemakers in Santa Barbara County were intrigued by the news.

“Santa Barbara County vintners tend to be more focused on farming, winemaking, and direct relationships with consumers than external validation,” said Alison Laslett, the head of the Santa Barbara Vintners. “That said, Michelin carries global credibility, so people are paying attention.”

Keith Saarloos of Saarloos & Sons hopes that if Michelin does show up, the results should simply carry the existing message forward. “It’s exciting because it tells the rest of the world what we already know,” said Saarloos. “Santa Barbara County wine is real. Grown slow. Made by farmers. Built on family, place, and patience. Michelin doesn’t make us great. It simply notices what’s been happening here all along.”

AJ Fairbanks, the estate director at Crown Point Vineyards, said there’s more curiosity than anything else right now. “Santa Barbara County producers already operate in a crowded landscape of critics, scores, and expert opinions, so there isn’t an automatic impulse to celebrate another layer of evaluation,” he explained.

He wonders how the Guide will approach the already crowded wine review realm. “There’s a healthy skepticism about whether this becomes genuine discovery or simply another re-anointing of the existing hierarchy,” said Fairbanks. “If, however, the Guide highlights wineries where guests can meaningfully engage with world-class wine — tasting it, understanding it, and realistically accessing it — then it could become a genuinely useful signal for travelers.” And that, he said, “would resonate strongly with many producers here.”

Questions remain over how the Michelin Guide will select regions to review. The culinary evaluations are in part funded by regional marketing organizations, so there’s an expectation that they may also seek financial support from vintners associations in exchange for coverage.

“That’s all very speculative right now,” explained Laslett. “Until Michelin outlines how wine coverage would work in practice, it’s premature to say what role, if any, regional organizations might play. Any future consideration would depend on transparency, value to producers, and alignment with our mission.”

Whether the attention would be worth any associated costs remains to be seen. But there is a strong sense that the Michelin Guide’s attention to Central Coast restaurants is helping bring more visitors to the nearby wineries.

“We’ve seen a clear crossover between Michelin-recognized restaurants and wine tourism,” said Fairbanks. Explained Laslett, “Santa Barbara appears more frequently in food-focused itineraries and dining-driven travel coverage that references Michelin recognition, particularly in out-of-market contexts where the Guide is used as a planning tool.”

The region is now more regularly grouped with culinary stories featuring Los Angeles or San Francisco, for instance, and people who travel to eat often add wine to their itineraries. “It’s difficult to isolate Michelin as a single causal driver,” she said. “But Michelin recognition has reinforced Santa Barbara’s positioning at a time when culinary travel is an increasingly important motivator.”

Amy Christine of Holus Bolus Wines can’t claim a direct correlation. “But, anecdotally, we do get a lot of people in the tasting room who have reservations at Bell’s for lunch or dinner, and are excited to go,” she said. “I am just not sure if that is what has brought them to Santa Barbara County, or if the wine has brought them, and the food follows. Chicken or egg? Hard to know!”

Of course, if it ever comes, no one seems to think the Michelin Guide‘s attention will hurt.

“If and when it happens, inclusion could raise international awareness, particularly among travelers who already rely on Michelin as a trusted source,” said Laslett. But with attention already coming through so many other sources, she clarified that it would be an “additive rather than transformative” recognition.

“Quietly, it is the attention we deserve,” said Saarloos. “I don’t know what the criteria is going to be other than I hope it’s fair and what the consumer has in mind. If they recognize who we truly are without having to change who we are, that would be amazing.”

Premier Events

Fri, Feb 13

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Galentine’s Candle Pour Party at Candle Bar 111

Sat, Feb 14

10:30 AM

Los Olivos

Valentine’s Couples Massage + Wine in Los Olivos

Sat, Feb 14

All day

Santa Barbara

Valentine’s Day Candle-Making Workshop

Wed, Feb 11

5:30 AM

Santa Barbara

San Marcos HS Jazz Concert & Silent Auction

Wed, Feb 11

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Chaucer’s Book Talk and Signing: Robert Landau – “Event-Art Deco L.A.”

Wed, Feb 11

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Galentine’s Day Celebrating Creativity and Sound

Wed, Feb 11

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIOS Grand Champion Cymbidium Orchid Awards

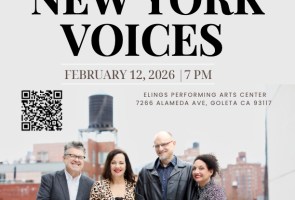

Thu, Feb 12

7:00 PM

Goleta

DP Jazz Choir in Concert with the New York Voices

Mon, Mar 09

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28

All day

Santa Barbara

Coffee Culture Fest

Fri, Feb 13 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Galentine’s Candle Pour Party at Candle Bar 111

Sat, Feb 14 10:30 AM

Los Olivos

Valentine’s Couples Massage + Wine in Los Olivos

Sat, Feb 14 All day

Santa Barbara

Valentine’s Day Candle-Making Workshop

Wed, Feb 11 5:30 AM

Santa Barbara

San Marcos HS Jazz Concert & Silent Auction

Wed, Feb 11 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Chaucer’s Book Talk and Signing: Robert Landau – “Event-Art Deco L.A.”

Wed, Feb 11 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Galentine’s Day Celebrating Creativity and Sound

Wed, Feb 11 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIOS Grand Champion Cymbidium Orchid Awards

Thu, Feb 12 7:00 PM

Goleta

DP Jazz Choir in Concert with the New York Voices

Mon, Mar 09 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28 All day

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.