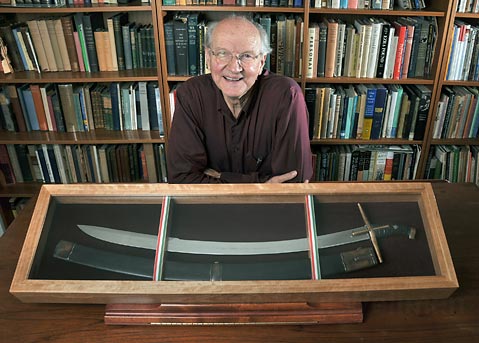

John Ridland Receives Hungarian Sword for Translation

Balint Balassi Award Bestowed for Work on the Hungarian Folk Epic Janos Vitez

On May 27, 2010, poet John Ridland received the annual Balint Balassi Memorial Award for his translation of the Hungarian folk epic Janos Vitez, or John the Valiant, at a ceremony in Los Angeles. This unusual award takes the form of an engraved ceremonial sword, and was administered by Balasz Bokor, the Consul-General of Hungary to the United States. Ridland, who was for many years a professor of English at UCSB, began work on this important translation in 1991, and the book was first published in 1999. I spoke with Professor Ridland recently about the poem, his experience, and his plans for the sword award.

What can you tell us about this poem?

They call it a folk epic. It’s part fairy tale, part romance, part adventure. There’s an orphan boy who lives in the village, and his sweetheart is also an orphan [Pause.] …if I get started, this could take a long time.

I see, why don’t you describe it from the outside then. What is the shape of the thing?

It’s 1480 lines of narrative, divided into 27 chapters, and it’s all rhymed in quatrains. It had been translated in iambic pentameter English couplets back in the 1920s, but that meter is all wrong for a folk epic. I took it back into four beat lines, basically anapestic, so that it rolls along the way it should.

How did you become interested in Janos Vitez?

In the mid-1980s there was a Fulbright Exchange with Hungary from UCSB. One professor came to History, and the other to the English department. The English professor became a good friend, and he invited us to come to Hungary, which we finally did in 1987. In one restaurant that we visited in Budapest there are murals illustrating this poem. They are quite nicely painted, and when I asked about them, I heard about the poem and how highly regarded it is there. When I got back, I discovered a prose translation in Davidson Library at UCSB. It was such a nice story that I thought it would be good to get it back into verse. I started the project in 1991, it came out on a press in Hungary in 1995, and then in a second Hungarian edition with illustrations by Roma children a few years later. It’s still in print on Hesperus in England and that’s how it is available now.

When translators bring epics from other cultures into English, they often have a point to make about our culture. What do you feel is the significance of Janos Vitez to a contemporary American audience?

This is a good question. For Hungarians, it’s a poem that’s read to them as children. Then they go to school and memorize it, and I have met half a dozen people who have memorized the whole thing. In part it is the humor, which is peculiarly Hungarian. There’s nothing like it in French or English.

Is it a satire of epic?

Satire? I think not. It’s more good-humored than that. The only people who might be offended would be Turks, who have occupied Hungary in the past. It was published in 1844, and Petofi died in 1849 as a victim of the Russian effort to put down the Hungarian version of the revolts of 1848. For Americans the point of it is pure pleasure. It’s also very moving. The girlfriend is held against her will by an evil stepmother, and the hero fights in several wars with the Turks and the Tartars. He wanders around in this weird geographical confusion that somehow puts him in India, and then India appears to be next to France. He acquires a companion, a silly old man, and then, due to his military prowess, he is offered the hand of the French princess. This gives Johnny an excuse to tell his life story as a way to explain that he must remain faithful and can’t marry the princess. The author, Petofi, had a sufficient education. I understand that he read the Odes of Horace. He’s later than Byron, but I don’t know for sure that he read him. It’s a similar kind of thing, insofar as Byron both wrote about these affairs and also became involved in the war of Greek liberation himself. But the style is different — it’s a folk style, and that was the challenge, to make it easy enough in English to reflect the popular idiom of the Hungarian original.

Was it completed all in one go?

No. He wrote the first 15 chapters, showed them around, and was told he needed to go back to work and finish it. At chapter 17 Janos comes back to the village and discovers the trauma that the wicked stepmother has inflicted on his sweetheart. Petofi had never been in a battle before writing the book, and in some ways he appears to have forecast his own death. But in the latter part it becomes fantastic, and there are giants and witches, and Janos attends a witches’ convention. He kills the king of the giants and gets a special whistle that allows him to call the other giants as helpers. He gets attacked, he blows the whistle, and the giants come to help him defeat the witches, the last of whom turns out to be the sweetheart’s wicked stepmother.

And then?

Janos goes beyond the seven seas, kills some big animals such as lions, and finally enters into a fairyland paradise of lovers. He can hardly stand it because he is alone, and he goes to a pond in the paradise to drown himself. He has a rose from his sweetheart’s garden that he throws into the pond, and it becomes her. He pulls her out of the pond and they become the king and queen of fairyland.

What was it like receiving the sword?

It was really funny. When I had to give the acceptance speech I said that it was strange for a poet to get a sword because we tend to think of the pen as mightier than the sword, and we tend to want to beat swords into ploughshares, but of course this particular poet, Sandor Petofi, did not get a chance to do that. It’s in a wooden box and it’s very sharp, so I would only take it out under extreme circumstances.

How does this award resonate with Hungarians today?

The Hungarians are strongly divided by politics. Former Communists are now socialists, and against them are arrayed a variety of center and right wing types. But I have friends on all sides of the political spectrum, and about this poem they can agree — it is a great representation of the Hungarian national culture. According to the Consul-General, there are 20 million Hungarian speakers in the world today, and they have a very strong sense of poetry. The award itself is named after Balint Balassi, who was a 16th century soldier and poet who was also killed in battle. The award is only 15 or 20 years old, and his name is on it because he was the first important Hungarian-language poet. He’s a figure comparable to Sir Philip Sidney as someone who was in on the making of national history and who was a soldier who died in battle. There’s a connection being made between fighting for the life of the nation and writing for the life of its language. It’s a renaissance ideal of the poet/hero.

What else can you tell us about the author, Sandor Petofi?

Petofi was poor, he walked all over the country, and he knew the people of Hungary firsthand. His original ambition was to be an actor. His first role in the national theater was the Fool in King Lear, but he was such a poor actor that he switched to writing poetry. He was prolific for someone who died at 26. He was a Romantic poet in the true sense, even dying young, like Keats. The Hungarians were very conscious of what was going on in Europe, and this poem is part of what they did to express a desire to be understood as European rather than Slavic. It’s a nationalistic version of Romanticism, and goes along with the Hungarian desire to get out from under the thumb of the Austrian emperor.