Competition Growing for Available Drinking Water

About 5 billion of the 7.5 billion people on Earth live in places where drinking water is becoming harder to find. The remedy is often to drill a water well deeper, but a new study published by UCSB researchers concludes there may be less drinking water in the United States than has been assumed. The researchers looked at fresh water in wells and the briny water below in the major sedimentary basins of the U.S., including the San Joaquin.

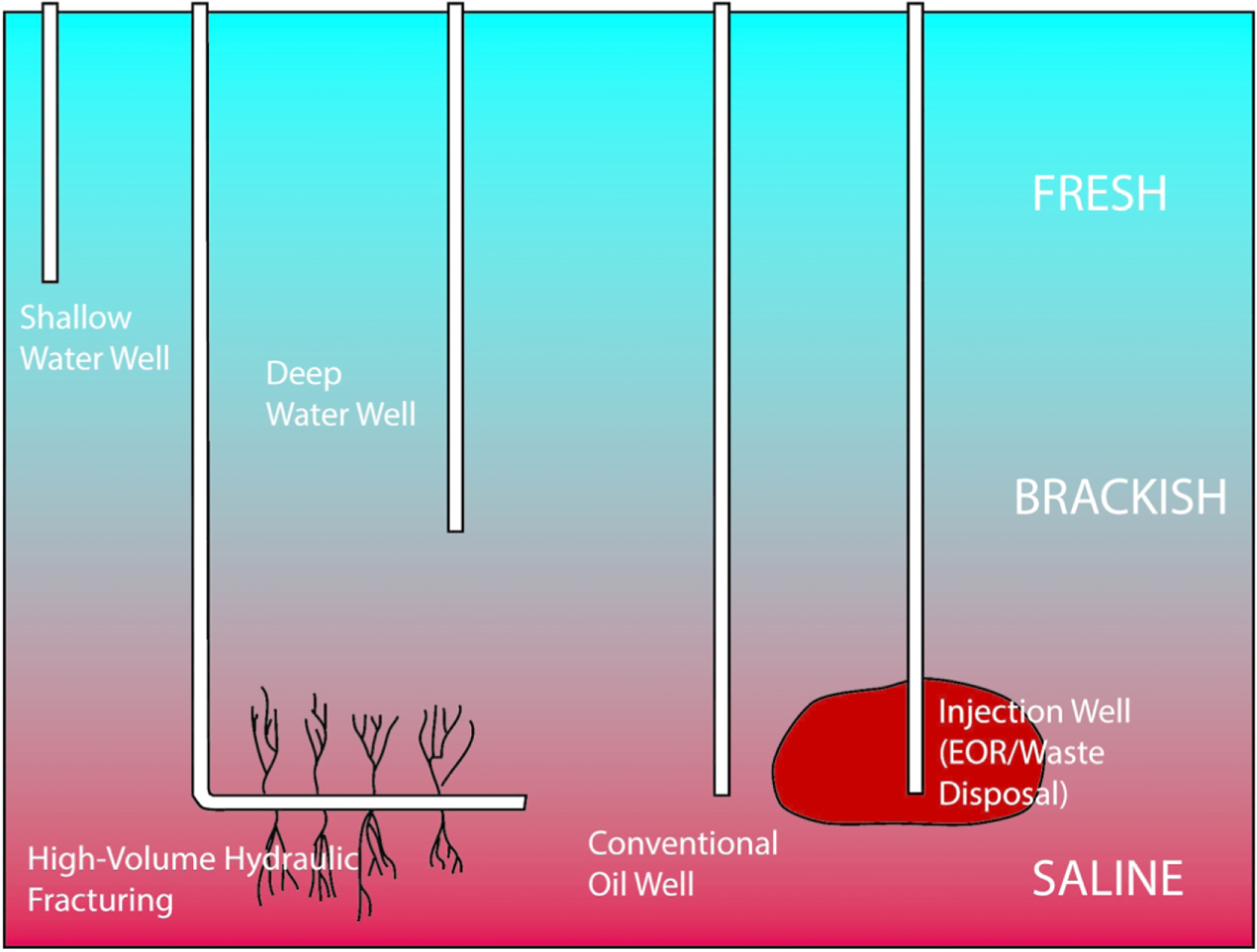

Contaminants from the surface plus those from injected fluids, as well as the fact that deep, old water tends to be brackish, are complicating the picture. One reason this matters is that brackish water, which has more salt or solids in it from eons of contact with underground rock, is being desalinated by more and more water companies to create drinking water, through processes like reverse osmosis.

The study builds on research done on groundwater levels across the country, “data mining” an impressive database from the U.S. Geological Survey, but this time from the “bottom up” in aquifers. “Combining top-down and bottom-up studies can give us a window into where fresh, uncontaminated groundwater exists,” explained study co-author Debra Perrone, an assistant professor at UCSB’s Environmental Studies department, “and where this window is getting smaller, either because the ceiling is coming down or the floor is coming up.”

The study identifies the competition for underground spaces among different users, including the oil and gas industry, said Scott Jasechko, a study co-author with UCSB’s Bren School. Some operations inject fracking fluids or discarded water from the oil-production process close to fresh or brackish waters, the study indicates, potentially endangering its drinkability. The distance between fresh water and the depth to which oil and gas drillers go varies from area to area and from well to well. Analyses like those in this study increase the ability to identify drinking-water wells that could be in jeopardy. “We should protect deep fresh groundwater,” said Jasechko. “Water is abundant on Earth, but only a small share is fresh and unfrozen. The more we learn, the smaller and more precious that fresh and unfrozen fraction seems to be.”

A footnote to the study, which was published in November in IOPscience with lead author Grant Ferguson of the University of Saskatchewan and Jennifer MacIntosh of the University of Arizona, mentions the federal Aquifer Exemption map, which shows the wells exempted from the Safe Drinking Water Act Underground Injection Control regulations; California is currently digitizing its information for inclusion in the map. For Santa Barbara, where water wells are dug anywhere from 60 feet deep (Santa Maria) to 2,000 feet deep (Gaviota), according to county Environmental Health, a report led by Perrone that would be locally relevant on deeper drilling is expected to publish in the coming year.