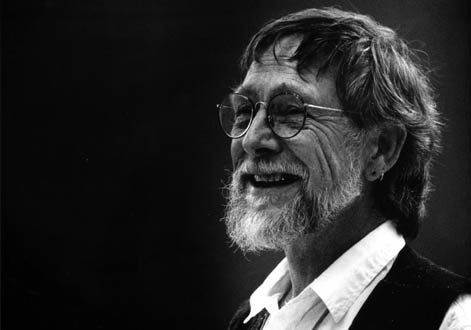

Eco-Poet Gary Snyder to Read at the Third Biennial Ojai Poetry Festival

A Mirror of Truth

Poetry and the Voice of the Earth, the theme of this year’s Ojai Poetry Festival, is a fitting heading for the work of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet/essayist Gary Snyder. Snyder’s new book, Back on the Fire, contains 27 brief essays that demonstrate his lifelong interest in “eco-poetics” (poetry on the environment), Buddhism, and various Eastern philosophies, and bits and pieces of his hip autobiography. The book’s title is a metaphor that suggests Snyder’s insight on the problems of humankind battling earth, as well as the “little fires” of the mind that bring forth the deeper meaning of things.

In the essay, “Writers and the War against Nature,” Snyder makes clear the role of the eco-poet: to be a “mirror of truth” and give in to a “heart of compassion.” In his haiku-like prose style, he argues, “For a writer to become an advocate for nature, he or she must become a lover of that vast world of energies and ecologies.”

Of course, Snyder practices what he preaches in his own poetry, essays, and life. He writes of his youth exploring the deep ecology of the West Coast, his days as a logger and trail crew worker, and his studied love of the sea during his stint as a merchant seaman. In “Lifetimes with Fire,” Snyder recounts his experience homesteading on “a piece of Sierra mountain forest land” where he felled trees and built his own cabin, now complete with “a wood-burning kitchen range” and, he mentions almost apologetically, a gassed-up chainsaw and a four-wheel drive truck. Snyder’s lifelong immersion in ethnopoetics-the poetries of distant others, outside the Western tradition-coupled with his back-to-nature lifestyle reminiscent of Thoreau, the Japanese master poet Basho, and the Chinese poet Han San, are the dominant themes not only of these essays, but most of Snyder’s poetry:

What the Indians

here

used to do, was,

to burn out the brush every year,

in the woods, up the gorges :

Fire is an old story,

I would like,

with a sense of helpful order,

with respect for laws

of nature,

to help my land

with a burn, a hot clean

burn :

And then

it would be more

like,

when it belonged to the Indians

Before

(from “Turtle Island,” 1974).

In “Thinking Toward the Thousand Year Forest Plan,” he advocates that we must plan 1,000 years ahead to ensure that our forests survive, in the light of “a growth-fueled economy” and “militant consumerism,” in order to “sustain both the wild natural world : to keep it diverse and flourishing, and : allow for human presence in and around the woods.” In all of Snyder’s essays, the underlying premise is we can and must learn to live in harmony with, not mastery over, nature.

Snyder’s cautionary meditations might seem somewhat remote for the average earthling. Not many of us homestead in the backcountry of the Sierra foothills, consider it one of our goals in life to work on a control burn of manzanita, or think of planning 1,000 years ahead to ensure the health of our forests, mountains, and rivers. Nevertheless, Snyder’s critics are few. Indeed, to the inspired, he is a sort of eco-guru, who with a monkish wink and a nod makes living in harmony with nature (and human natures) as easy as one breath at a time. But the “real work,” one might humbly suggest, is for poets and conservationists to reach the overwhelming majority of humans who live in steel cities covered with asphalt, under clouds of questionable air, and drink cancer-laden water. When asked by Susan Deming in 2001, “Can poetry change the world?” Snyder’s answer was “Ha!” a Buddhist koan, no doubt, meaning “??????”

Paul Lobo Portuges is the author of six books of poetry, most recently The Body Electric Journal.

4•1•1

Poets Gary Snyder, Sherman Alexie, Sandra Alcosser, and Mar-a Melendez will read at the Ojai Poetry Festival, taking place on May 18 and 19. For more information, visit ojaipoetryfestival.org or call 289-4873.