In Praise of an Imperfect Memory

As the old observation goes: Today’s sorrow, plus time passing, equals tomorrow’s comedy. Memory can be kind in that way. Today we cry, tomorrow we laugh.

We complain endlessly about our skeedaddling memories, yet there is more to consider than whether or not we can remember where we put our keys. Sometimes our unreliable memories can be most helpful and forgiving.

Think of it this way: We will often remember the giddy feeling of the champagne and not the hangover, ergo the tendency to pop the cork on that next bottle of bubbly. Women who’ve gone through childbirth tell me that if they could actually remember the pain they went through, they would never choose to go through it again.

According to the Nobel Prize-winning Princeton psychologist Daniel Kahneman, we tend to repeat experiences that seem more palatable in hindsight than they actually did at the time. In other words, our experiences and our tendencies to repeat them have less to do with pleasure and pain-as one might suspect-but more to do with our fallible memories of pleasure and pain.

I have noticed that we filter our memories differently. There are those who only remember the pain of life, ignoring the more blessed moments. And then there is the “half-full memory” crowd that only remember the good times, forgetting all those dark corners. I happen to fall in the latter category. People close to me will sometimes remark on my ability to forgive and move on. Truth is, I really can’t remember the pain and drain of those bad times. It is not some moral highness I possess; it is probably just good, old-fashioned denial.

In other words, the fidelity of our memories can be very much a function of our individual coping styles. Some will happily wear yesterday’s memories today like outdated fashions, while others will deliberately cut themselves off from memory, retaining no keepsakes from the past. Some will become overtaken by a memory in a way that they can’t escape; such is the case of PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Of course, there is also the garden-variety neurotic who stews in the past, like some Woody Allen bobblehead.

There is the boon of not remembering all those terrible things we did once upon a time but wish we hadn’t. I remember my father saying that a man with a clear conscience probably has a poor memory. And then there is someone else’s father-Franklin Adams-who opined: “Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.”

And sometimes an abstracted memory can provide us with some of life’s greatest pleasures. Have you ever noticed there is no summer day in the present that compares to the remembered summer day from childhood where there was a swarm of fireflies on a balmy night that smelled of honeysuckle?

On the other hand, we must remember those who forget the past are more likely to repeat it in the future with potentially dire psychological and interpersonal consequences.

So what is better? The harsh comptroller of exact memory, or the more romanticized sieve of memory? It’s hard to say. One thing to consider is the well-researched finding that optimists do live longer. And it does seem that to be an optimist you need an errant memory. So maybe the fallibility of our memories-something that can cause chaos in the short run when we are trying to remember why we just walked into our living room-can be a boon to our longevity.

One of my mother’s favorite sayings is, “My imperfect memory has served me well; it has given me roses in winter.” This lovely and lively woman will be celebrating her 87th birthday in fine form next month.

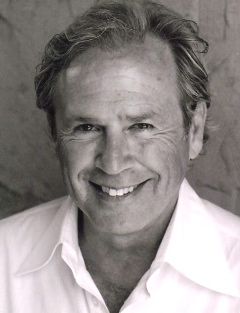

Dr. Michael O.L. Seabaugh is a licensed clinical psychologist with a psychotherapy practice in Santa Barbara. Comment at healthspan@mac.com and visit his Web site/blog at HealthspanWeb.com for more information on the topics covered in this column.