Warhol About to Pop

The University Art Museum Exhibits the Early Andy

There’s something wonderful about the last few moments before a raucous house party, when there are only a few people there and the hostess is still rushing around, putting things away and pushing aside the tables and chairs to make room for the crowds and the dancing. It’s the calm before the storm, but juiced up with electricity, and there’s the thrilling sense that soon all that delicious empty space will be filled with the heat and thunder of loud music, animated conversation, and potentially seductive physical contact. Entering the University Art Museum a week ago with Acting Curator Natalie Sanderson, who has just completed work on Andy Warhol Presents, a fascinating exhibit that includes not only early Warhol but also previously unseen drawings by his protege, Edie Sedgwick, I felt that excitement, and starting tonight at the show’s opening party, you can expect to catch it, too.

The show’s core concept is thatWarhol was already on track toward his career as an important fine artist as early as the mid 1950s, when his primary modes of expression were drawing fashion illustrations and designing window displays for now-defunct New York department stores like I. Miller and Bonwit Teller. It’s a compelling thesis, and one that a careful study of the artist’s subsequent development bears out. Even as recently as 20 years ago, very few art historians would have identified these seemingly whimsical commercial drawings of ladies’ shoes as harbingers of Warhol’s massive, repetitious celebrity portraits on canvas, never mind the frighteningly subversive 1960s paintings of auto wrecks and electric chairs. Much has changed since then, and today, the idea that sometimes a shoe is just a shoe is no more acceptable to the huge audience that loves Sex and the City or The Devil Wears Prada than it is in dated academic theories of the commodity as fetish. In this show, as for Warhol, a shoe is a shoe is a shoe, and then some.

Warhol approached his central artistic subject -appearances-through his primary preoccupation: fame. The road that led him there began in fashion retail, a world of glossy magazines, women’s dresses, and thousands upon thousands of sexy high heels. Working in Manhattan’s burgeoning gay underground of window decorators and fashion illustrators in the late 1950s, Warhol met many lifelong friends and more than a few closeted fine art peers such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. This fickle, competitive scene not only prepared Warhol for two decades of hustling couture customers for portrait commissions, it also initiated him into the higher echelons of those who sculpt desire for a living: the buyers, photographers, editors, and designers whose collective sense of style must embrace the new and endorse perpetual seasonal change. It was this training that allowed Warhol to gauge the climate of the art world so successfully in the early 1960s when he finally brought his own line, Pop, to market.

The cultural triumph of international celebrity worship, and in particular of Warhol’s maddeningly voracious and patently cynical variation on it, is now stunningly complete. Fascination with famous people and their consumption of luxury goods has moved from subculture to mainstream so boldly in just the last decade that it is sometimes hard to remember that there was a time before millions of American teenagers knew about Manolo Blahnik and Jimmy Choo. Whether or not the media attention now lavished on lifestyles and wardrobes of the rich and famous continues, the genesis of the “It’s Good to Be Young, Rich, and Beautiful” nation can be traced to a remarkably specific and now distant moment in history: the metaphorical five minutes before Andy Warhol’s 25 years of “15 minutes of fame” began. What this exhibition allows us to do is visit the Warhol atelier before it became a Factory, and contemplate the subtle vagaries of inspiration that coalesced around 1962 into the juggernaut of Pop.

To that end, there are two crucial details in Andy Warhol Presents that demand our full attention: the line and the can. The line is broken, and it is everywhere. Beginning with his fashion illustrations, Warhol engaged in a continuous practice of inflecting his images, whether they were self-created or appropriated, through a variety of printmaking processes. The original monotype technique that figures so largely in this show may well be the most important, more significant in its own way than the better-known silk-screening that he used to produce most of his acknowledged masterpieces. Drawing with ink on a wax-sealed paper, Warhol created the image he wished to print, then laid the still-wet paper face down onto another sheet, this time of an absorbent, nonsealed surface consistency. The result was a broken line, directly related to the original one traced by the artist’s own hand, but attenuated by chance, skipping and trailing off in unexpected, yet relatively controllable ways. This monotype technique was Warhol’s first experiment with printmaking, and it remained in the background as the fundamental experience that informed nearly every subsequent strategy he employed for randomizing and lending texture and feeling to his images.

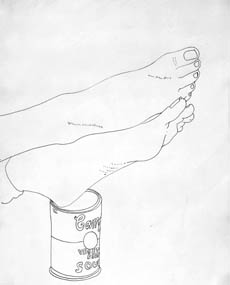

The can is of course the Campbell’s soup can, and the single image in this show in which it appears-a drawing of a man’s bare feet resting on the top of a can-is the exhibit’s most arresting piece. To fully appreciate what is happening here, one has to understand that this delicate drawing predates the famous soup can multiples, which Warhol did not produce until just before his Ferus Gallery show in Los Angeles in 1962. The inclusion of the bare feet of a man connects all those fanciful women’s shoes, with their punning, playful references and elaborations, to Warhol’s intimate life as a gay man. If you are familiar with Norma Desmond, the heroine of Sunset Boulevard, then you can think of the feet, and all those crazy shoes, as a kind of spiral staircase, and there at the base is the Campbell’s tomato soup can, batting its false eyelashes and calling out in a throaty voice, “Mr. Warhol! I am ready for my close up.”

4•1•1

Andy Warhol Presents runs July 11 through October 7 at UCSB’s University Art Museum, with an opening reception on Thursday, July 12, from 5-8 p.m. Museum hours are Wednesday-Sunday, noon-5 p.m.; admission is free. For more information, call 893-7564 or visit uam.ucsb.edu.