Cattle Drives through the County

Get Along, Little Doggies

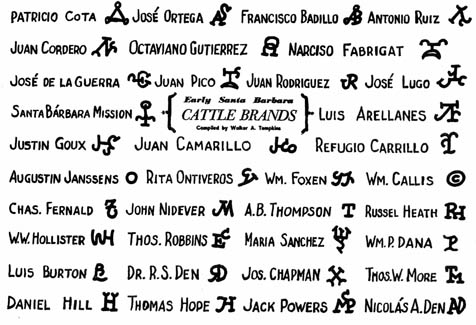

Milpas Street has always been a busy thoroughfare; before the cars, there were the cows. The following excerpt from Yankee Barbare±os by historian and writer Walker A. Tompkins tells of a time when Santa Barbara’s Eastside and the surrounding area was the main artery for marching cattle through town, which often caused unwanted mixing of local herds with those passing through, much to the dismay of Santa Barbara ranchers.

Many cattle drives went through Santa Barbara County during the 1870s, some of them originating as far south as San Diego. The herds generally numbered 1,500 to 2,000 steers, handled by 12 vaqueros per thousand head. Their destination was usually the railhead at Soledad, from whence they could be shipped to San Francisco. Trail bosses hoped to cover 10 miles per day, but later reduced the distance to six miles to keep from “chasing all the tallow” off their cattle.

If the rains had come by October, cattle drives could be expected in the county as early as January, when the grass was at its peak. Drives would continue on through July or August, depending on grazing conditions. There was an unwritten law, carried over from the Mexican rancho days, that trail herds could cross any large grant provided they were kept moving at a reasonable rate. No ranchero ever wanted visiting cattle to fatten on his grass for extended periods.

One source of friction in Santa Barbara County, as elsewhere, was cattle loss that occurred when local cattle mixed with a traveling herd and drifted out of the owner’s jurisdiction. Transient cowboys rarely wasted any energy cutting local brands out of a herd at bed-ground and certainly not on the trail. There was a strong suspicion among Santa Barbara rancheros that many a “stray” departed along with herds in transit, with the knowledge and even the connivance of the traveling herds’ owners. If cattle losses became too prevalent, a ranchero felt justified in sending a cowboy along with a herd to represent him at the loading chutes in Soledad; there he could tally up all cattle bearing his employer’s brand.

The cattle drives entered the City of Santa Barbara via the beach side of Ortega Hill; the land route through Montecito’s East Valley offered too many attractive side canyons and heavy woods where a steer could vanish forever. By sticking to the beach, a heard could be kept intact and hit the land again at the Place of the Woodticks west of Ortega Hill, thence inland at the Salt Pond at modern Salinas Street. Milpas Street became part of the cattle trail, which skirted the base of Mission Ridge from the vicinity of today’s [Santa Barbara] Bowl to the end of the hill at the Old Mission. Domestic cows had prior grazing rights to the boulder-strewn pasture of the upper Eastside, as far as East Mission Street. At this point, the trail herds were hazed westward onto the county road leading to the Goleta Valley. Gaviota Pass was the drovers’ favorite route over the mountains, although a few large herds had been known to traverse San Marcos Pass on their way to the Santa Ynez and Los Alamos valleys.

Overland cattle drives dropped off sharply following the drought of 1877. Going into the ’80s, the drives ceased to be large-scale operations and were ended altogether around the turn of the century, when the railroad was completed.

4•1•1

The Yankee Barbare±os: The Americanization of Santa Barbara County, California, 1796-1925, by Walker A. Tompkins. Published by Movini Press, Ventura, California. 527 pages; $79.95. Available at area bookstores or online at yankeebarbarenos.com.