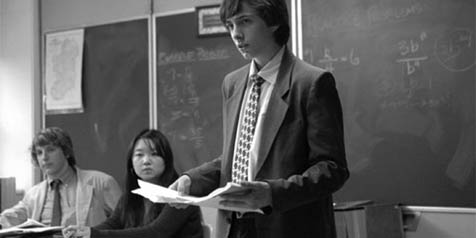

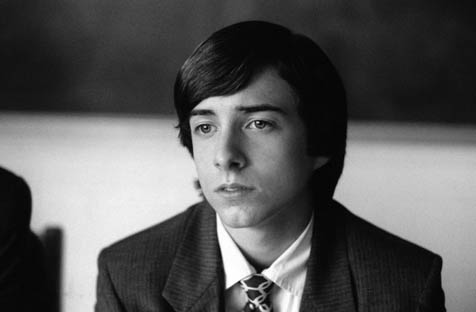

Launching Rocket Science by Jeffrey Blitz, Winner of Best Director at Sundance

From Spellbound to Stuttering

Ateenager tackles the mysteries of life, love, and public speaking in Rocket Science, a wry comedy of adolescent angst by Jeffrey Blitz, director of the Academy Award-nominated documentary Spellbound. Making his feature narrative debut, Blitz leaves behind the conventions and cliches of coming-of-age tales to instead conjure a world where everyone, regardless of age, is befuddled by desire and the longing for human connection. Mixing humor with a compassionate regard for his characters and their idiosyncrasies, Blitz creates a film about the little insights that can emerge from, and ultimately eclipse, the agonies and disappointments of youth. I sat down with the director to discuss his film.

How did you transition from making documentaries to your first feature film? Spellbound was on the film festival circuit for a few months-and I was in financial debt because of the film. We hadn’t sold it yet, and we thought it would never find an audience. An executive at HBO saw the film and said, “I want to hire you to write a screenplay that hopefully will become your first fiction film.” And the fact that anybody wanted to hire me to do something that wasn’t against the law was really exciting.

You stuttered as a child like the lead character in Rocket Science. In writing the script, how much did you draw from your personal experience? I stuttered and I stutter still, but my stuttering was quite bad when I was in high school and then I joined up on my public speaking team. But I didn’t want to create a story where I felt obligated to stick to the facts of my own life and have to adhere to it closely. I didn’t want to get into a game where I was trying to recreate my own experience, not only because I felt that wasn’t the most imaginative way to write a screenplay, but autobiographical films, especially by American filmmakers, kind of give me a rash. I just think most American filmmakers haven’t lived lives that are interesting enough to warrant sharing them with an audience. So, I wanted to just take basic facts from my life and some of the emotional stuff I thought I could understand well and then build a story I thought would be funny enough and have enough drama in it that it could actually entertain an audience.

Spellbound is about the competitive nature of spelling bees and Rocket Science is about the competitive world of debate. Coincidence? No. I like the way audiences have expectations for the way that competition films will play out. And it’s fun as a filmmaker to play with those expectations, to feed into them, to let it be the structure for the drama and then let it unfold or to act like it’s going to go that way and then thwart it, as Spellbound and Rocket Science tend to do.

In Spellbound, you followed young kids with your camera, and in Rocket Science, you directed them. How was that different? One of the things I brought into Spellbound that was sort of my hunch-and I think it proved to be right-is that very often when adults come into the lives of children, at the beginning they act like they know so much more than those kids do and they treat them like they’re some other species or something. I really wanted in making Spellbound to go in and to genuinely be interested in what these kids have to say and to try to listen to them in the way I felt most adults would not. Sometimes that was genuine on my part and sometimes I had to go in and act the role of someone who was genuinely interested in stuff an adult is generally not interested in hearing about. But I tried to bring that same spirit into Rocket Science, where even though the kids who we got did not have a tremendous amount of acting experience, I wanted them to know I was really open to whatever they wanted to bring to it and their ideas.

The lighting of films that deal with personal growth normally begins dark and then gets brighter toward the end. Rocket Science does the opposite. Yeah, actually I insisted upon that-the last scenes of the film are at night. I felt the movie ends up being about embracing the questions that don’t have easy answers. And so to suggest that there is a clear path to enlightenment where the answer suddenly becomes known at the end was exactly the wrong idea for me. The great conversations I’ve had with my parents oftentimes were conversations that I had in the quiet and the peace of night. And during the day when there are other people around, you just can’t connect the same way.

Talk about the music score. It’s a great soundtrack. When I was writing the script, I was listening to this band Clem Snide, this little indie band. And many of their songs were about, coincidentally, teenage punks in Jersey. It’s sort of a weird niche as a band. So I felt like the spirit of this band and Eef Barzelay, who’s the lead singer, had sort of seeped into the script when I was writing it.

What lessons did you learn from making documentaries that you brought to your first feature film? Well, the funny thing is that people want to believe that making a documentary is a completely different experience than making a fiction film. But they are actually very close. I think the process of visual storytelling and figuring out how to build a story-you’re actually exercising the same muscles. But I think when you work on a documentary you learn to embrace the happy accident. I think that even in a fiction film, there are so many variables that you are keeping your fingers crossed for the happy accident.

The narrator in the movie adds a very different texture. I loved the idea that in a movie about a kid who has no voice, and is in search of a voice, that there is a character who is nothing but a disembodied voice and, for all of the inarticulateness of the film, that there is a character who exists as someone being able to say the very right thing. That, in a world where everyone is struggling to find voice, there can be some outlet, there can be some way to express what is deeply felt and thought.

You submitted Spellbound to Sundance, and you got turned down. But then a couple years later, you bring Rocket Science and win best director. Was that sweet revenge? Ahh, sure. Sure it was.