The Link Between Astrology and Palmistry

Batya Explores the Early Years of Chiromancy

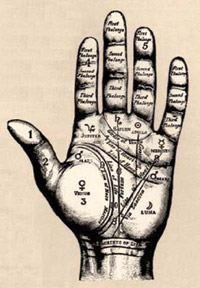

I have touched briefly before on how the practice of palmistry was still connected to astrology during the early Western European Renaissance (see “East Meets West”). We have also explored how each finger and mound were once thought to correspond to an individual planet. In fact, the link between palmistry and astrology was not broken until well into the 19th century, when palmistry had already developed its own level of symbolism.

But palmistry as an art expanded considerably through its connection to the more mysterious art of astrology. The same sort who became involved in palmistry became equally as absorbed in astrology, and vice versa. Mystics studied all aspects of the occult and devised ways to connect its many tangential spokes.

Alchemical and astrological research went hand in hand. Books published on either subject usually had a chapter on palmistry, leading to further creative collaborations. In 1647, the Frenchman Jean Belot’s Les Oeuvres assigned each of the phalanges a zodiacal significance. Each finger was said to have housed three astrological signs. Each augmented the power and nature of the characteristic governed by a particular finger.

Belot practiced outside of the court. He remained obsessed with occult sciences and tied the usual chiromancy symbols with astrological glyphs. He aimed to deepen the significance appointed to different parts of the hand.

Palms were usually discussed in this period as being an expression of the complexities of the macrocosm (the human, their astrological sign, and the position of this sign within the cosmos) within the microcosm (the hand, the relation of this hand to the whole human figure, and the presenting connection between the human figure and the transcendental plane of astrology).

For example, Rudolph Goclenius published Aphorisma Chiromantica in Nuremberg in 1592. He then went on to lecture at Wittenberg University, and later procured yet another job at Marburg. He combined medical, philosophical, and astrological research with his interest in chiromancy.

Interested readers might also have a look at Joannes Rothman’s Chiromantiae Theorica Practica. Through a close examination of hands, this volume, published in 1595, anchored the abstract theory of astrology in the world of flesh and blood. Palmists devoured Rothman’s book, which Katherine Saint-Hill still attested to using in the 19th century – 400 years after its original publication. Ahead of the age, the book and its author offered understandings of how a birth chart and a palm reading could interrelate, even producing congruent forecasts.

Rothman’s popular book was the only German palmistry manual translated before the 20th century.

Posters from London in 1651 advertised the publication of Fabian Withers’ Book of Palmistry. This book also declared a connection between the rules and manuals of divination, astrology, and the nature of the planets.

But palmistry in England became rather disrespected during the 1650s. Distinctions began to be made between astrology and astronomy. Even the magic of alchemy evolved into a more scientific chemistry.

The need for accuracy became the chief aim of the sciences. At the same time, the desire for systematic approaches to the investigation of nature pushed chiromancy, with its higher, more intuitive understandings, into the background. Fear and superstition derailed the driving force of inner knowledge practices, such as palmistry.