Big Wave Woman

One Winter Story Tells of Sarah Gerhardt's Rise from Poverty to Surfing Giants

It seems everyone and their cousin is surfing these days. Yet despite the crowds in the lineup, very few riders become big-wave surfers. Of those, only a precious few ever attempt the hazardous conditions of Northern California’s legendary Maverick’s, a monstrous break whose 20- to 50-foot waves pulverize the icy waters just north of Half Moon Bay.

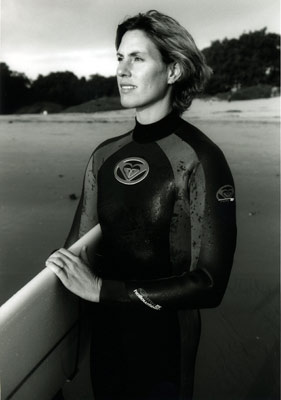

For a woman to succeed in the male-dominated world of big-wave surfing is even rarer. Maverick’s was home to an exclusively male coterie until 1999, when Sarah Gerhardt eroded the big-wave mecca’s gender barrier, making surf history as the first woman to slice across the terrifying wave.

Any one of Gerhardt’s many accomplishments inspires awe. She’s also the first female tow-in surfer and is half of the only big-wave surfing husband-and-wife duo in the world. She has a Ph.D in Physical Chemistry, teaching at the collegiate level. She’s raising two children. These are difficult feats to achieve under any circumstances, but Gerhardt’s had tremendous obstacles to overcome. Growing up, she was the sole caretaker of her severely disabled mother, and the two lived in poverty, often homeless. Learning to surf in high school offered an escape from the hardships of home, and her passion for chemistry kept her in school.

Hawaii filmmaker Sally Lundburg and San Francisco filmmaker Elizabeth Pepin trace Gerhardt’s unforgettable story in their award-winning documentary, One Winter Story. Offering an unprecedented glimpse into the male-dominated world of big-wave surfing from the rarely-seen perspective of a woman, One Winter Story includes the requisite, beautifully-shot montages of spectacular waves. But the poignant story of Gerhardt’s challenging background, sensitively rendered by Pepin and Lundburg, makes the film deeply resonant. Her remarkable journey from poverty and despondency to accomplishment and personal serenity is a testimony to her determination and belief in herself.

This film will be shown on Friday, April 18, at the Marjorie Luke Theater as part a benefit event for Santa Barbara Channelkeeper, which protects and restores the Santa Barbara Channel and its watersheds. It will be preceded by music from Omar Cowan and Jason Campbell & the Drive, and the filmmakers will be on hand for a Q&A session after the screening.

We shared one of our own over the phone recently. What follows is an extended version of that conversation.

What prompted you to make this film about Sarah Gerhardt?

Sally Lundburg: I had known Sarah from surfing on the Big Island. At that time there were only a few women surfing regularly at the surf spot I was at, and she really stuck out as an amazing surfer. Throughout the next couple of years, I heard brief mentions in surf magazines that she was really charging big waves, and then that she had surfed Maverick’s.

I left Hawaii and moved to San Francisco for school, and took up a real interest in documentary film. I felt like there wasn’t much out there in terms of film and video pieces about regular, non-professional woman surfers, so I decided to do a short series of film portraits about them.

My first one was actually about Elizabeth, which was how she and I got to know each other. I wanted to move on to a different kind of women surfer – Elizabeth surfs longboards and small waves – and I knew Sarah was surfing Maverick’s and not really being documented. I was really curious what it was like for her out there: what it was like with the men in the lineup, what those waves are like, what her everyday life was like.

So I called and asked her if she’d be interested in taking part in what was supposed to be a 15-minute portrait. I did the first interview, and I had no idea of the scope and the depth of things she’s gone through, in terms of her mother’s disability and illness, and of the family history of poverty. I realized that it was a much deeper, longer, more interesting story than I had even imagined, beyond the scope of what I knew how to do as a filmmaker. Elizabeth and I had become friends, and she’s an Associate Producer at KQED, so I asked her to join me in the project.

Elizabeth Pepin: I’ve been surfing since 1986, and shooting women’s surf photos since 1997. I started shooting photos because I was really disappointed in the reaction of the surf magazines to the growing women’s surf movement. For a long time, they pretty much ignored women and surfing. Every once in a while, when they did do something, it was basically a glorified bikini model thing-never any women on a wave.

When I started seeing more and more women in the water in the mid ’90s and the surf magazines still were ignoring them, I was really frustrated. So I started bringing my camera to the beach and shooting portraits of women that I’d meet on the beach after I’d surfed myself, and then moved into shooting from the water with a big lens and water housing. So Sally’s reasons for doing this really coincided with my own wish to see more images of powerful women surfers. Still to this day, there are not as many as I wish there were.

SL: Because the women are out there!

EP: The reaction to my photographs from other women is that it never even occurred to them until they finally started seeing other women in the water – because there were no role models, no examples – that this is something that they could do. That’s the unfortunate side effect of the surf industry and surf media being mainly dominated by men. I don’t think it even crosses their mind how important it is to have role models that girls and women can see and say, “I can do that, too.”

VIDEO OF THE MAKING OF ONE WINTER STORY

A few territories that Sarah’s pursued are traditionally considered men’s domain – big-wave surfing, and achieving a doctorate in Physical Chemistry, which is not a field in which you find a lot of women either. Has she encountered any roadblocks in either pursuit in terms of gender?

SL: I think for Sarah’s story, it’s really important to go back further than where she is now, because I really think it’s the reason she’s been able to be very independent and determined. She was raised by a mother who was in a wheelchair, and from the age of six, Sarah was her sole caregiver. She had to dress her mom, make her food, and help her in the bathroom. They were very, very poor, but had a really close relationship, and during that time her mom got her master’s degree.

In the film, Sarah talks about how difficult it was for her being so poor – she was made fun of at school, they didn’t have enough to eat. Her mom helped her learn it’s important and okay to go solo, to be okay with who you are and where you’re at.

So she says very clearly she doesn’t really think about being the only woman. She just thinks about what she wants to do and she just goes for it.

EP: That’s the message we’re trying to impart to people in the film. It’s really resonated with our outreach screenings in schools and with youth groups. A lot of kids have a really tough time, especially in junior high and high school, when they’re made fun of, there’re hard things going on at home, and they just feel like giving up. The film shows them someone who had a horrible time. They weren’t just poor – part of the time, they were homeless and lived out of a car.

SL: Despite being teased horribly at school and having to dig food out of the garbage can at lunch because she didn’t have any food to bring to school, she didn’t give up and she had these dreams that she focused on and made happen. That’s the message of the film and I think that’s why it’s been so successful and really hit a chord with a lot of people, not just surfers.

EP: I think people should know this is not your typical surf film. We don’t even call it a surf film. It’s a documentary about a woman who has had success as a surfer. But it is an experimentally shot documentary, not your typical ripper-shot surf film with loud music.

Something that you both share with Sarah, besides being avid waterwomen yourselves, is that you’re making your lives in what is generally considered men’s territory: adventure-sports filmmaking. What has that experience been like?

SL: In terms of making the film and shooting her out at Maverick’s, the other filmmakers and videographers were generally really welcoming and helpful, and we actually received a really warm welcome from the surfers there as well. I think that had more to do with who Sarah is, because most people have a lot of respect for her as a person. So when people learned we were making a project about her, we were welcomed.

EP: I think, in a lot of ways, being women filmmakers out there was an advantage. People were really helpful and went out of their way to help us find Sarah when she was out there. It’s half a mile out in the ocean, and you’re filming from a cliff – to see her among a sea of all these other black wetsuits is really challenging, so some of the other videographers and photographers would help us spot her. People took Sally out on the jet-ski to film, because I was way too chicken to go out myself.

Where it did get a little weird was at all of the extreme sports or surfing-oriented film festivals. We’re the only women filmmakers there. Our film got picked for X-Dance, one of the side festivals of Sundance. It was all guys, and I was there by myself. There were these three Hooters models giving out the awards. Every time one of the guys would win, the girls would kiss them, and they’d put their arms around the girls and make gestures.

We actually got nominated for three awards, and I was thinking, “Oh god, what if I win? I’ll have to go up there with these Hooters models, what am I supposed to do?” Fortunately, I didn’t have that problem. At least we got nominated, which was absolutely incredible.

Did you receive any support from the surf industry or surf media?

SL: We did initially approach Roxy. Sarah was a sponsored Quicksilver team rider at the time, and it kind of seemed to us like a no-brainer – she was this amazing woman making surfing history – that they might want to help us with the film. We were not given any assistance or interest: or money.

How did you ultimately finance it?

SL: It was really hard. We only received one $4,000 grant, so we had to be creative in terms of how we got the money to make the film. That’s why it took us so long – five years from start to premiere. But it would not be the film that it is if it hadn’t taken us this long.

I really love the quality of film, but it’s definitely not cheap to shoot. We chose to shoot the whole film in Super 8 and 16mm for a number of reasons, one being financial. Shooting in different formats really gives it this archival, home movie feel.

When we started to shoot in film and realized how expensive it was going to be, we turned to getting all kinds of different film stocks wherever we could scrounge it up for free, or cheap. I was working at the San Francisco Art Institute school store after graduating, and was able to buy on-sale and out-of-date film, and also process some of the film there.

EP: I used to own a record store and had a huge collection, which I sold. Sally sold all her surfboards. We had a “bake sale” on the beach, but instead of baked goods, we sold my surf photographs and the film Sally had made, and a few other things. We had several fundraisers, an art auction, sent out fundraising postcards, drained our bank accounts.

This was a huge labor of love.

EP: We made our movie exactly the way we wanted to. It was an unusual way, and people responded positively, which is so rewarding. I work at a PBS station, and have to make stuff that’s pretty straightforward. I don’t get to make films the way I would want to make them. It was very freeing and extremely scary to be able to make this film. But it was great and I’m glad Sally asked me to do it.

4•1•1

One Winter Story screens on Friday, April 18, at 6:30 p.m., at the Marjorie Luke Theatre as part of a benefit for Santa Barbara Channelkeeper. The evening also includes a raffle and live music from Omar Cowan and Jason Campbell & the Drive. Tickets are $12. Call 563-3377 or see sbck.org.