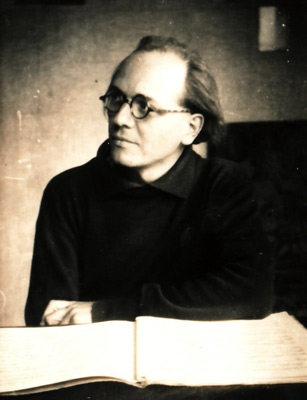

Music Academy Pays Tribute to Composer Olivier Messiaen

Jesus Looks

Ask musicians to describe the work of Olivier Messiaen, the marvelously original composer whose centennial is being celebrated this year, and certain words keep turning up.

Evocative. Imaginative. Spiritual.

And, most often of all, hypnotic.

“Audiences tend to be transfixed and transformed by his work,” said Richard Feit, vice president of artistic programs and operations for the Music Academy of the West. “You look at music a little differently after you’ve heard it.”

The Music Academy is marking the 100th anniversary of Messiaen’s birth with performances throughout the season, including a short orchestral work on July 19. But the music of the French composer, who died in 1992, is front and center this coming week.

Tuesday’s faculty Chamberfest at the Lobero concludes with Messiaen’s best-known and arguably greatest work, Quartet for the End of Time. The following evening, pianist Christopher Taylor will perform his massive, two-hour-long work for solo piano, Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jesus in the new Hahn Hall.

Of the work’s enigmatic title, Taylor said, “It’s a rather difficult phrase to translate. The idea is the infant Jesus is looking at, or imagining, different scenes. There are views of the star and the cross and various other symbolic representations. It’s quite a mystical conceit, but you don’t have to buy into all the symbolism to appreciate the greatness of the music. Its power speaks for itself.”

Anyone who expects uncluttered spiritual uplift will be disappointed: There is plenty of darkness and dissonance in Messiaen’s music. “Angels are terrifying,” Feit said. “He knew that.”

Messiaen knew men could be terrifying as well. During World War II, he was a soldier in a French Army unit that was captured by the Nazis. In 1940, he was sent to a prison camp, where the music-loving commandant was thrilled to learn he had a composer in his midst.

Encouraged to write, Messiaen composed Quartet for the End of Time for himself and three of his fellow inmates. They gave the piece its premiere in January 1941, before an audience of several thousand of their fellow prisoners.

“It’s a monumental work of 20th-century music that also happens to have an extraordinary story behind it,” said New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, who was on hand for last month’s Ojai Festival. “The incredible thing about the quartet is its fusion of sounds that don’t necessarily seem to belong together. The rhythms of the piece are unstable and constantly changing. When he refers to ‘the end of time,’ Messiaen means it not only in the sense of the ‘Book of Revelations,’ but also in the sense of tempo and rhythm-the end of regular time and the beginning of a new kind of rhythm that is always fluctuating.”

“Again and again, at one moment he is giving you some ferocious dissonance, and the next moment is some incredibly sweet, simple, tonal chord,” Ross continued. “It’s all in the alteration and combination of these different sounds. That’s how he gets the incredible intensity. The dissonance becomes all the more crushing and terrifying for having appeared in the neighborhood of those much sweeter sounds. The sweeter sounds become all the more precious for appearing in that harsh landscape. I think that’s the magic of Messiaen. If it was all lyrical, tonal music, it wouldn’t have the same effect. Jaws wouldn’t drop in the same way.”

Taylor, a member of the music faculty at the University of Wisconsin, was introduced to Messiaen at age 17 by his piano teacher in Denver, Francisco Aybar. “He had the idea I should play a couple of movements from the Vingt Regards,” Taylor recalled. “He assigned me numbers 7 and 10 [of the 20 sections], which I took to right away. It was always in the back of my head that I would learn the other 18. But my hand wasn’t forced until 2000, when a presenter from Columbia University called me and said they were interested in me playing the whole cycle. Learning it took something like half a year. Since then, I’ve probably performed it a dozen times.”

But it hardly has gotten routine.

“It is an endurance feat,” Taylor said. “It requires a lot of concentration. There are some passages in particular where he gets the motor going and doesn’t let up. The same idea will come back over and over again, but each time it’s varied slightly. That can be quite confusing to the fingers and the brain.”

That’s quite a comment from a man who earned a degree in mathematics from Harvard and programs computers as a hobby.

Balancing that complexity, however, is an overwhelming sense of emotional genuineness. Messiaen used music as a way of expressing the awe he felt living in God’s universe. In doing so, “He came up with a musical language like nobody else’s,” said Feit. “He’s someone who is worth discovering.”

4•1•1

Christopher Taylor will discuss Messiaen with Alan Chapman at an evening of Musical Insights at Hahn Hall on Monday, July 7, at 7:30 p.m. The Chamberfest recital that includes Quartet for the End of Time is on Tuesday, July 8, at 8 p.m. in the Lobero Theatre (33 E. Canon Perdido St.). Taylor’s performance of Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jesus takes place on Wednesday, July 9, at 7:30 p.m. in Hahn Hall. For more information, call 969-8787 or visit musicacademy.org.