Picasso in Two Centuries

S.B. Museum of Art's "Picasso on Paper" Exhibit Reveals Much About Both the Spanish Artist and the Museum Itself

On Friday, September 5, at the opening of the new Santa Barbara Museum of Art exhibition Picasso on Paper: Drawings and Prints from the Permanent Collection, 1899-1967, the group gathered to celebrate resembled the show-small and powerful. For an institution that has done so much to expand its audience through the wildly successful Nights events, by making Sundays free, by encouraging visits by schools, and through so many other programs, the Picasso on Paper opening represented a chance to thank the core of contributors who have been crucial to the museum’s ongoing development, many of whom have direct connections to its founders.

As the museum’s director, Larry Feinberg, moved skillfully among the various groups of patrons admiring the show, clusters of eager listeners formed around the different sorts of experts in attendance. Painter Mary Heebner’s sparkling and insightful observations about Picasso’s art led her to express amazement at the great things that the original donors to the museum were able to accomplish. Distinguished art dealer and philanthropist Robert Light remarked that, while he knew and appreciated what had come before-he was a personal friend and adviser of Wright Ludington, the collector who was, more than any other single figure, responsible not only for this show, but for the museum itself-he thought that it was now “time to look ahead at what is coming next.” And Alfred Moir, the curator of Picasso on Paper and professor emeritus in the history of art at UCSB, basked in the culmination of many decades of patient work learning the ins and outs of prints and authentication, all the while absorbing a great deal of the huge body of critical work devoted to Picasso, the greatest 20th century artist.

Gazing around the galleries, one felt how all these fascinating pictures on the walls were intimately related to the elite corps of equally fascinating connoisseurs and intellectuals gathered. Picasso on Paper, which draws 23 of its 25 superb works from the museum’s permanent collection, represents not just the remarkable strength of the artist Picasso, but also the foresight and curatorial genius of SBMA, and of the people who were responsible for creating it. The show was made possible by the foresight and generosity of the museum’s founding generation, but it’s equally an expression of the spirit of its new leadership. It’s a great show that deserves not only the large audience it will no doubt receive in coming weeks, but also the focused attention of anyone who cares about museums, about history, and about the future of art.

Museums and the 21st Century Market for Art

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art was founded in 1941, a year as golden in the history of art collecting as it was dark in the history of civilization. Wright Ludington, who contributed half of the works in the current Picasso exhibit, had succeeded in assembling a museum-worthy collection of Greek and Roman antiquities at perhaps the last time in history that such a thing could be done without being arrested for theft of cultural property. It was a time when people of relatively modest means, at least by today’s billion-dollar standards, could buy original paintings by well-known artists at prices that now sound like accounting errors.

For instance, it was in 1941 that New Yorkers Sally and Victor Ganz purchased “La Reve,” a Picasso painting that hung in their dining room for decades, for $7,000. When the Ganz collection was auctioned at Christie’s in 1997, “La Reve” fetched $48.4 million, and sold to an anonymous bidder who may never exhibit the work publicly again. And, although he fails to crack the current top five of artists with the highest priced individual paintings ever sold (they are Pollock, de Kooning, Klimt, van Gogh, and Renoir, in that order), Picasso remains the overall biggest seller of all time by a substantial margin, with nine paintings ranked in the top 30.

The astounding sums now commanded at auction by great modern art have to do with several factors, not the least of which is the fact that older works-such as Leonardo da Vinci’s “La Gioconda,” or, as she is better known, the “Mona Lisa”-seldom if ever come on the market. But by far the most noticeable recent change is the worldwide frenzy for high-priced art that kicked in with the spectacular fortunes made in the 1990s. Although some of the pictures that have gone for more than $100 million were sold as early as 1987, the majority have changed hands within the last five years. When the early, Rose Period Picasso “Gar§on a la Pipe” sold at Sotheby’s in New York in May 2004 for $104 million, rumors immediately began to circulate that the buyer was Guido Barilla, the Italian pasta billionaire; but if Barilla was the buyer, he isn’t talking. Whomever the lucky moneybags was who funded the winning bid, the picture itself, which depicts an exquisite young man smoking something other than tobacco, is almost certainly cooling out in a temperature-controlled Swiss bank vault.

Although they are hardly the point of the art as art, these skyrocketing prices for modern masters ought to motivate us to look with fresh eyes at what we have here in our own museum’s permanent collection, and at what we are doing with it. Blockbuster exhibitions such as the Museum of Modern Art’s Picasso retrospective of 1981 have become prohibitively expensive; the insurance alone would cost more than even a sold-out show could conceivably return. It was possible to see Picasso in a large retrospective this year at a venue outside of the museums that are solely dedicated to his work, but that big show of 186 paintings closed on September 4-and it was in Abu Dhabi. This is one of the reasons why SBMA director Larry Feinberg told me in the spring that he is “determined to find ways to create programming that is educationally valid, and that deals with top-tier artists like Picasso, without going to the possibly unmanageable expense of borrowing major works from around the world.” Picasso on Paper offers a great example of how imaginative curators and directors can sidestep the financial obstacles that have been thrown in their way and continue to address the public’s interest in seeing the very best work that has ever been done.

Early Picasso and Spanish Santa Barbara

Much of the excitement involved in this particular show has to do with its strengths in Picasso’s early representational work-items from the eras known as the “Blue” and “Pink” or “Rose” periods. There were urban outcasts in Paris long before Pablo Picasso arrived there from Spain at the turn of the 20th century, and there were artists, such as the medieval French poet Fran§ois Villon and the Italian opera composer Giacomo Puccini, who had portrayed la vie bohme memorably before Picasso’s celebrated “Blue” and “Rose” periods of 1901-1907. But it took the enigmatic young Catalan painter’s highly personal and uncanny skill as a draftsman to channel the expressive genius of the great tradition of Jean-Antoine Watteau through these bands of emaciated acrobats and blind street hustlers, broadcasting a mixed message of desperation and soul to the world. Throughout the rapid sequence of unprecedented stylistic innovations that followed-Cubism, Neo-classicism, and Surrealism-Picasso displayed what the art critic Clement Greenberg has called a “radical, exact, and invincible loyalty to certain insights into the relation between artistic and non-artistic experience.” In other words, Picasso had profound creative integrity.

These valuable early Picassos from the Blue and Rose periods once belonged to Ludington, the deeply cultured Montecito resident and international art connoisseur, and a man whose various residences here are among the finest examples of Santa Barbara’s greatest contribution to modern art, the brilliant buildings designed here by George Washington Smith and Lutah Maria Riggs, among others. By showing these pictures together now, Picasso on Paper exhibition curator Moir offers an opportunity to reflect not only on the career of Picasso, but on the whole history and mission of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and on the great historical shift in the creation and understanding of art to which it, and the modernist-influenced Spanish-style mansions of Montecito and Hope Ranch, belong.

In this modest yet highly instructive show, Picasso stands at the beginning of another new century. Having arrived in Paris at the turn of the 20th century only to become the world’s most prestigious artist, Picasso now greets the turn of the 21st century in Santa Barbara as an avatar of whatever profound cultural changes may occur in this century, and the high stakes for which artists and museums will be playing over the next hundred years.

Why the Blue and Rose Periods Matter

If Cubism is so obviously the big bang at the beginning of modern abstract art-and it is-what makes these earlier, merely representational periods in Picasso’s career so important? The Blue and Rose periods are crucial because, through his evocative portrayal of outsiders and the restriction of his palette to successive single dominant hues, Picasso set two mighty ideas in motion.

First, his choice of subject matter connected him with universal images of suffering that would only become more poignant as the dreadful history of 20th-century Europe ground on. But he also played ironic modernist games with the meaning of that misery: using blindness as a metaphor for sight, for instance, or employing starvation as an allegory of taste. By painting the Paris underworld in this ambivalent manner, Picasso signaled his departure from simple sentiment in the direction of something more complex and layered.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, these first great period styles of Picasso’s drew a blueprint for what an important modern artist’s career could be. Where once the standard artist’s career path led straight through apprenticeship and collaboration to mastery of the atelier, Picasso’s self-isolating approach drew a twisted line of personal periods and styles that effectively cut him off from both tradition and fashion, even as he shaped the latter and entered the former.

By moving through the Blue and Rose periods on his way to Cubism and beyond, Picasso established the heroic ideal of a career in which every successive aesthetic solution eventually becomes the backdrop for yet another act of self-transcendence. Through Picasso’s example, constant reinvention of self and medium became the modernist norm. To work through and then abandon a series of powerful “periods,” and to create in each a dominant style that changed other people’s perceptions of what was possible-this became the modus operandi of the archetypal modern artist. These early pictures of harlequins, strong men, and tumblers that Picasso observed eking out their existence at the edge of Parisian society, deprived of color, health, and warmth, have, through the alchemy of connoisseurship and their creator’s subsequent reputation, come to stand for a moment of absolute artistic potential, a time when the world pulsated in anticipation of the birth of a new way of seeing, and when it was still possible for a solitary artist alone in his studio to conjure for them what felt like a totally new approach to life.

Modernism’s First Supper

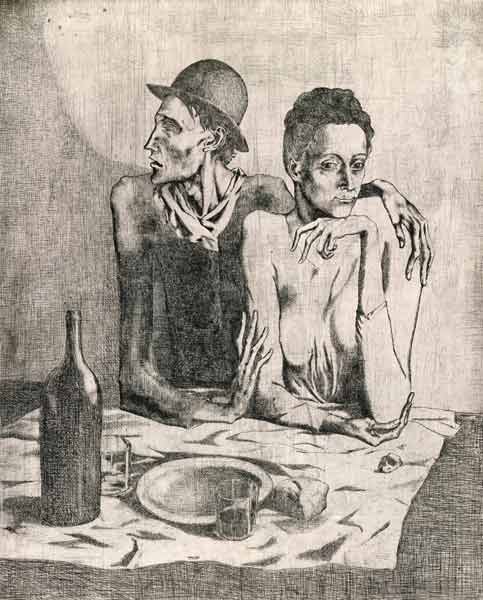

Despite its extraordinary familiarity-virtually everyone will recognize this image-“The Frugal Repast,” a Picasso drypoint print from 1904 now on display at the museum, retains the shock of the new and reveals a potent irony. A poor couple, unbearably thin and wasted looking, sits at a table littered with the remains of their mostly liquid lunch. The man appears to be blind, and the woman, her hair cropped close, looks away while sitting listlessly within her companion’s existential embrace. Dead broke, yet seemingly beyond the reach of material concerns, the couple in “The Frugal Repast” are nevertheless chic in a way that signifies in retrospect the promise that modern art would provide not just a new way of making objects, but a new way of approaching life in the city. Their self-possession and the dignity of their weary pose are such that blindness in “The Frugal Repast” can seem to stands for insight, and poverty for the imagination. By portraying his own art as a “frugal repast,” Picasso at once prophesied the rigors of the abstract cubist period soon to come, and winked mischievously at the magnificent decadence of the banquet years in which Paris became the center of the artistic world. Dubbed “the million-dollar print” by collectors when it first began to attract such bids at auction, “The Frugal Repast” belongs among a small handful of prints that can be said to have defined early modernism.

Looking around elsewhere in the show, one sees many other familiar figures from the Picasso oeuvre. There’s the strong man Tio Pepe from the family of Saltimbanques, sitting alone and exhausted in an exquisite drypoint print simply called “Clown Resting” from 1905. Another etching from the same series, “The Bath,” captures the strange charm with which Picasso imbued the makeshift domesticity of traveling circus performers. At the end of the gallery are a pair of large drawings, both made while on holiday in Italy with his good friend Igor Stravinsky. “Italian Peasants” and “Woman with a Pitcher,” both from 1919, are shown with a small photo of the Egyptian woman who was the basis for the latter composition, revealing that Picasso’s penchant for idealization was already at that time in full gear.

Across the hall, the later period works convey much of the rich, imaginative life present throughout Picasso’s cubist and surrealist phases. “Picador and Personages III” from 1960 and “The Musketeer” from 1967 are both gifts of Mary and Leigh Block. They show the 20th century’s greatest draftsman toward the end of his life using brush and pencil with undimmed skill. No Picasso show, no matter how small, would be quite complete without a portrait of the photographer and Picasso mistress Dora Maar. The one in this exhibit is a lithograph from 1936 that conveys the essence of this complex and dynamic woman with the single strong gesture-as in Man Ray’s famous photograph of her, the upper left half of her forehead is obscured.

The Meanings of the Minotaur

When asked if he had a favorite image in the exhibit, curator Moir answered without hesitation, saying that “if there were one I could slip into my coat on the way out the door, it would certainly be the ‘Blind Minotaur Guided by a Little Girl in the Night’ of 1934-1935.” In one of the many excellent wall cards he has written for the show, Moir reveals the enigmatic origins and direction of this beautiful aquatint. The Minotaur, with his powerful outstretched arm and expression of passionate despair, is almost certainly a figure of the artist, and the little girl a portrait of Marie-Therse, Picasso’s young lover of the time. Yet within this primary set of identifications, several secondary options swirl and provoke. There was a blind art dealer in Paris, Leon Angely, who famously was led about and assisted in buying art by a young girl, and this may be in part what Picasso is remembering here-a scene from his early days as a starving artist dependent on even the most disreputable of agents-the blind buying from the broke.

The most exciting idea that Moir has to offer about the “Blind Minotaur,” however, is that it points ahead to the monumental antiwar painting “Guernica” of 1937. The Minotaur, in this view, stands for the plight of humankind about to enter into an awful decade of world war and genocide. Through this connection, Picasso on Paper touches what many consider the artist’s greatest single contribution to modern art. Even those contemporary painters who occasionally try to minimize Picasso’s impact on their work fall back in awe at the achievement represented by this turning in the great artist’s career. In a powerful interview with the author and playwright Anna Deavere Smith, Brice Marden had this to say about Picasso’s “war painting”:

“Guernica.” It’s amazing, a really amazing painting. It’s like, “Oh, we haven’t done our war painting.” That’s the last great war painting. : Very direct-you feel the hand going through with a kind of passion-you know. And it’s like this thing-it’s like with the caves-you see some bull on the wall of the cave, and it’s there with this kind of awe. And you know it’s like the human is in awe of this thing. And because of this awe, they have to make, they have to express. This you know. : And it brings up that question: Why haven’t we made our war painting? – from Anna Deavere Smith’s Letters to a Young Artist (2006)

If, as Marden so deftly recognizes, Picasso’s Minotaurs recall the awe of primitive man in the presence of the great life-force represented by the bull, then what are we to do with this larger question that such an identification raises, the one about “Guernica,” the question of “why haven’t we made our war painting?” Perhaps the greatest thing about such an important artist is precisely this, the way his work brings up issues that, once they are out on the table, can’t easily be put back in the drawer.

In a recent conversation with SBMA’s newest curator, Julie Joyce, an expert on contemporary art who has been brought in to head the museum’s efforts in that area, the work of Kim Jones came up. Jones is a Los Angeles-based performance artist who served in the Vietnam War, and Joyce put together a beautiful exhibition catalogue for a Jones retrospective when she was with the Luckman Gallery at Cal State Los Angeles. Sometime during the week that I was working on Picasso, a package arrived at The Independent from Joyce, containing the book, which is called Mudman: The Odyssey of Kim Jones. Although Joyce readily acknowledged during our interview that Jones-whose primary artistic manifestation involves an elaborate costume of dirt and sticks that he wore to portray himself as Mudman-would most likely not be a part of what’s planned for Santa Barbara, turning the pages made me think again about what Marden had said, and about what he had asked for. The biggest questions raised by Picasso on Paper, the ones like “why haven’t we made our war painting?” or “what’s a museum for?” are not going to be answered right away. But with a team this enterprising, and capable of spanning the distance between Alfred Moir, who at 84 can see Picasso in the same light as his specialties, Caravaggio and Van Dyck, who is to say just what we will get next.

4•1•1

Picasso on Paper shows at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art until December 7. See sbmuseart.org for more info.