Harvey & Dan: That ’70s Show

The Path from Neighborhood Politics to the Assassination of an Icon

I first met Dan White in October 1977- 13 months before he snuffed out the life of Harvey Milk.

As a long-haired, rookie reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, I’d arranged to interview White, a 31-year-old firefighter and ex-cop running for the Board of Supervisors, at his campaign headquarters, a blue-collar neighborhood storefront plastered with “Unite and Fight with Dan White” signs. I asked that day about a statement in his campaign brochure: “I am not going to be forced out of San Francisco by splinter groups of radicals or social deviates.” Many read his declaration, including misspelling, as code-an attack on San Francisco’s influx of gays. One was Harvey Milk, a high-profile gay activist and camera store owner running for supervisor in a more liberal district. White insisted he wasn’t smearing gays, but referring to violent leftists then conducting terrorist bombings in the city.

“Crime is number one with me,” he said, in explanation.

Milk and White both soon won the election. No one could have known it at the time, but a year later their lives would intersect in a few seconds of violence and horror, a tragic climax to a tumultuous decade. On November 27, 1978, the ex-cop assassinated Milk and liberal mayor George Moscone at City Hall.

Three decades later, the awful story is now retold in Milk, Gus Van Sant’s acclaimed film, infusing the screen lives and deaths of Milk, Moscone, and White with operatic dimension. As a reporter who knew and covered the three men as politicians and news sources, though, it still feels strange to view them as historic figures in an epic drama. My mind’s lasting images are more prosaic, street-level shards of memory about long-ago political wars and the party-hearty swirl of San Francisco in the 1970s.

The town was polarized, political power up for grabs. The entrenched business establishment sought to reinvent a working-class port city as a Manhattan-style finance and tourist center, while an aggressive neighborhood movement fought to preserve a Santa Barbara-like scale and quality of urban life. Backed by minorities, labor, and environmentalists-and the charismatic Rev. Jim Jones-liberal Moscone squeaked to victory in 1975 over a cranky real estate man channeling conservative, white homeowners from upscale, verdant fog-belt neighborhoods.

The stakes grew the next year, when liberals passed a measure to elect supervisors by districts instead of citywide, bringing more than 100 grassroots candidates out of the woodwork. I’d covered these folks for the hip alternative weekly, so the stodgy Chronicle hired me to help cope with the crazies.

Milk, a perennial progressive candidate, was the best known of the district election crew. I’d covered him in a previous race, and enjoyed gossiping with Harvey about politics, sitting on a battered crimson sofa in the back of his tiny, failing camera store in the gay mecca everyone called the Castro.

One of Milk’s loyal supporters was a stringy-haired entrepreneur named Dennis Peron. He ran Island, a hippy-dippy restaurant where Harvey held fundraisers, but his passion was managing an underground marijuana supermarket the cognoscenti called Big Top. When the cops raided Dennis one night, shooting him in the leg before arresting him, I was assigned to write it. I called Harvey for background, and he worked me like a ref; after the piece came out, he sent me a little handwritten note, applauding my “sensitivity on a sensitive story.”

By contrast with Harvey, Dan was a novice, campaigning against 11 other unknowns in a gritty district framed by two freeways on the southern boundary of the city. White Catholics-resentful about newly arrived Asian, Latino, and gay immigrants-populated its single-family houses with postage-stamp lawns.

Researching the race, I met candidates for coffee in an old bowling alley, and filed a story naming White a frontrunner, on the strength of his precinct operation and stoked by his large, Irish family, and police and fire-department pals. Some of his rivals soon called me, complaining that White’s troops were bullies who intimidated them at candidates’ events. Dan called too, seeking advice about an editorial board meeting; he mentioned that campaign donations had picked up following my story. After the assassinations, I’d beat myself up over that.

When Harvey and Dan both won, the TV stations took to interviewing the two together, the gay, Jewish ward heeler and the straight-arrow Catholic choir boy symbolizing the diversity of district elections. The pair gained a little rapport; Dan assured Harvey that his campaign reference to “social deviates” was about junkies, not gays.

Rapprochement didn’t last.

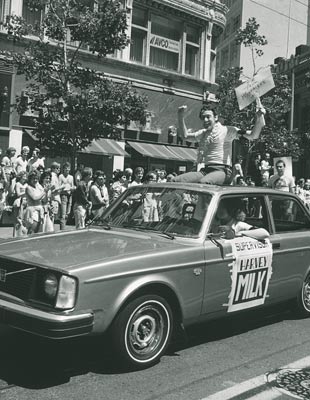

At City Hall, Milk dove into the swim, while White struggled to make headway. A major ham steeped in opera and theater, Harvey had a gift for making news and a keen eye for image. Assignment editors at the paper considered Milk, with his shameless self-promotion, a pain in the ass. But despite their grumbling, he often made page one: Harvey’s “human billboard,” a line of handsome, young gay men displaying campaign signs on Castro Street; Harvey, arriving at Island’s election-night celebration on the back of his leather-clad, female campaign manager’s motorcycle; Harvey, marching to inauguration, arm draped languorously on the shoulder of his slim, Latino lover; Harvey, beaming over Moscone’s shoulder at the signing of Milk’s antigay discrimination bill.

But Milk was never content with being just the gay supervisor. His finest politics-is-local triumph pictured him inspecting his shoe after “accidentally” stepping in dog doo at a press conference in the park about his “pooper scooper” legislation: “Anybody who solves the dog-shit problem can be mayor,” he told me more than once.

White, meanwhile, struggled. He proudly announced formation of neighborhood watch teams to combat a wave of violent street crime, but was promptly blasted in the press for “vigilantism.” He found more success fighting for the mostly white Police Officers Association against a discrimination suit filed by black officers. Moments after the supes narrowly voted behind closed doors to accept a settlement, White called me in the press room, asking for a meet; then he swore me to secrecy, handed me the documents, and innocently asked, “Can you get this in the paper?” After my story led page one the next morning, public outcry about the settlement’s terms torpedoed the deal.

But Dan lost his biggest fight. He’d promised to block a city-financed center for troubled teens from moving to an old convent in his district. At the board, he was humiliated, losing 6-5. He seethed at Harvey, who cast the crucial vote against him after promising support. Dan stopped talking to Harvey.

He also began acting strangely.

In summer 1978, he ranted about a routine, Columbus Day street-closure request by a colleague from the Italian, North Beach district, thundering that the city was “trapping people in their homes.” After losing 10-1, he slammed his fist on the leather chair of the measure’s sponsor, muttering a vague threat. His behavior was so weird that board president Dianne Feinstein whispered for him to cool down. Years later she told me, “I couldn’t believe it-he was flushed, he was angry. There was a visceral response [that] should not have been there.”

Politically frustrated and beset by money problems, White withdrew. The paper reassigned me to the state politics beat. In early November, freshly moved to Sacramento, I was shocked to read that Dan had abruptly resigned.

Then Jonestown erupted.

Jim Jones, Moscone’s old ally, led the mass murder suicide of his flock in Guyana, and White became old news. Behind the scenes, the Police Officers Association pressed him, desperate for his vote on the discrimination suit. While Dan pleaded for the seat, Milk and others convinced Moscone to name a liberal replacement instead.

Moscone planned to announce the new supervisor at 11:30 a.m., on Monday, November 27. Minutes before, White slipped into his office, shot and killed him, reloaded, then walked across the hall and executed Milk. An hour before his life ended, Harvey giddily told a friendly City Hall aide that Moscone had given him a heads-up about the appointment. She asked if he planned to attend the announcement.

“Are you kidding?” Harvey smiled. “I wouldn’t miss this for the world.”