California’s Economic Pandemic

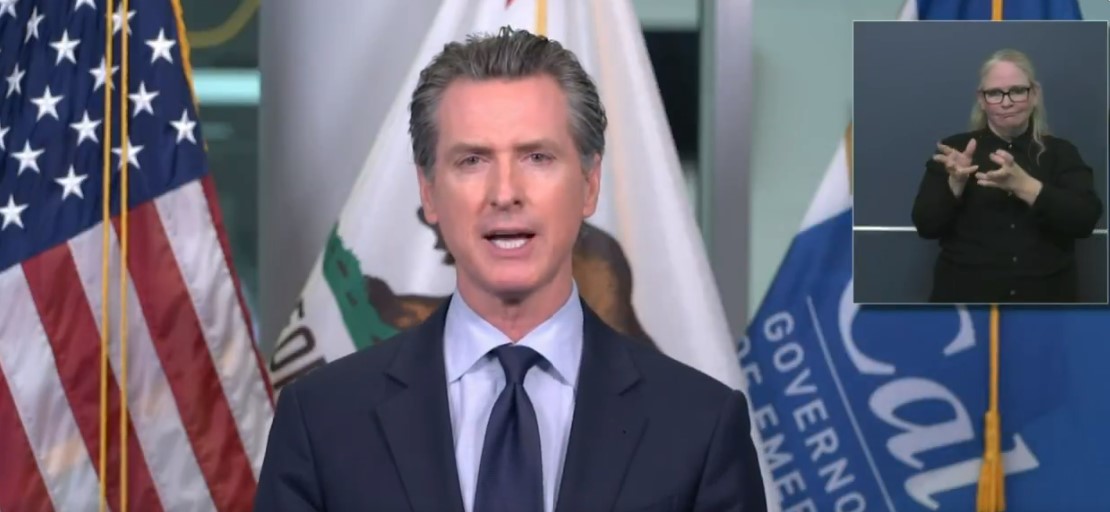

Amid Massive Uncertainty, Gov. Newsom Sends Lawmakers a Crisis Budget

In 2018, Jerry Brown unveiled his final budget as governor with some words of counsel for his successor.

“What’s out there is darkness, uncertainty, decline, and recession,” he said in starting his last year in office. “So good luck, baby.”

The man always had a knack for peering into the future.

Brown’s words reverberated in Sacramento this week, as California’s Legislature began urgent consideration of Governor Gavin Newsom’s emergency state budget plan to withstand the sudden and calamitous COVID-19 pandemic recession.

“The world has changed dramatically since I proposed my budget in January,” Newsom said on May 14. “Now our state is in an unprecedented emergency, facing job losses and shortfalls in record time.”

Four months earlier, he presented a rosy, $222 billion proposal for the coming fiscal year, bristling with new spending — plus a budget surplus.

Now, after a two-month shutdown of California’s economy, he’s sent lawmakers a revised, $203 billion plan that includes cuts in education, health, welfare, and other programs — plus projected multiyear deficits and a looming $54 billion shortfall for the fiscal year beginning July 1.

Facing a June 15 constitutional deadline to pass a balanced budget, legislators are scrambling to act amid the wreckage the virus inflicted on state finances.

An exercise in apportioning economic pain, their actions will affect millions of students and their teachers and hundreds of thousands of public employees, along with four million newly unemployed workers and the growing rolls of poor, homeless, and otherwise vulnerable residents, immigrants, and children in need of medical, welfare, and food programs — not to mention every taxpayer who uses state roads, parks, and beaches or lives at risk of earthquake, wildfire, or flood.

“We’re dealing with an unprecedented combination of a public health emergency and an economic crisis,” said Santa Barbara Assemblymember Monique Limón, who serves on a key budget subcommittee overseeing education.

“The reality is that that there are no good options,” Limón added. “There’s Hard Choice A and Hard Choice B.”

BY THE NUMBERS: Sacramento confronts its worst fiscal mess in a decade as more than 3,000 people have died from COVID-19 and more than 80,000 have been infected; the statewide unemployment rate heads toward 25 percent; thousands of small businesses fear they may never reopen; and the pandemic widens the economic gulf between California’s rich and poor.

Newsom’s $54 billion deficit estimate combines a shortfall in the current fiscal year, which ends June 30, and another in the 12 months that follow. It has two basic causes:

About three-fourths of the total traces to the precipitous collapse of California’s three main revenue sources — income, sales, and corporation taxes — as the loss of wages slashed consumer spending and cut corporate profits.

The balance represents unexpected spending increases, including about $7 billion in emergency response to the coronavirus, plus rising costs for people out of work and increased demand for health and social service programs.

Thanks to Brown, the state is better prepared than in previous budget crises: He championed a “rainy day” emergency reserve fund, which now holds about $16 billion.

Newsom’s fiscal strategy cobbles a solution from multiple sources: about $8 billion from reserve accounts; $8 billion in already approved federal relief funds; $6 billion in canceled new spending proposed in January; $4 billion in suspended business tax breaks; $2 billion in a rescinded planned payment on unfunded pension liabilities; and $10 billion from borrowing, transfers, and deferrals via internal accounting moves.

As the governor and Legislature enter an intense month of negotiations, the budget that emerges will be shaped in part by answers to five key questions:

WHAT WILL TRUMP AND MCCONNELL DO? Newsom’s plan rests precariously on $15 billion of what are called “trigger cuts” in budget-speak: proposed reductions for schools, higher ed, health and welfare, parks, and other services that would take effect — unless the federal government delivers another relief package.

The Democrat-dominated House recently passed a new $3 trillion bill including money for cash-strapped states, but Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and President Donald Trump have scoffed at the legislation, portraying it as a partisan “bailout for blue states.” California’s budget now depends on when — or if — a compromise emerges in bitterly divided Washington.

HOW MUCH WILL LAWMAKERS PUSH BACK? Soon after the pandemic hit, the Legislature vacated the capital, leaving Newsom to act unilaterally under his stay-at-home and other emergency orders — and to spend billions on coronavirus response with scant oversight or transparency. Now, some lawmakers are asking tough questions about his fiscal management of the crisis, and the Legislature’s independent budget analyst has warned that elements of Newsom’s plan would give the governor some unprecedented new powers.

“In a number of areas across the budget, the Governor makes proposals that raise serious concerns about the Legislature’s role in future decisions,” Legislative Analyst Gabriel Petek wrote this week. “We urge the Legislature to jealously guard its constitutional role and authority.”

HOW BIG IS THE DEFICIT, AND HOW BAD WILL THE RECESSION BE? There is disagreement about the scale of the projected deficit: Newsom’s baseline for his $54 billion estimate is the budget plan that he proposed in January, including billions in new spending; the Legislative Analyst foresees a more manageable, if still severe, shortfall somewhere between $18 billion and $31 billion, pegging it to actual current spending, not the governor’s start-of-year proposition.

The $18-$31 billion estimate range rests on two different scenarios for California’s recovery, one a relatively quick rebound and the other a more stubborn recession; the governor’s projection rests on a worse-case, if not worst-case, scenario of sustained tax revenue losses.

WHAT ABOUT NEW TAXES? Newsom’s plan contains only one modest revenue side increase — suspension of $4.4 billion of current business tax breaks.

As budget hearings begin, look for advocates for public employees, teachers, and social welfare groups, perhaps as well as left-liberal Democrats, to suggest more taxes to address the problem; education and labor groups already have qualified a November ballot measure, dubbed the “Schools and Communities First Initiative,” to raise $12 billion annually from corporations by amending California’s iconic Proposition 13, and it will be politically instructive to see how much support coalesces amid the gloom of recession.

WHAT WILL SCHOOLS DO? Leaders of more than 1,000 school districts are struggling with perplexing questions about whether, when, and how to reopen schools in the fall; faced with their own budget deadlines, school districts confront massive uncertainty, both about the course of the virus and about how to pay extraordinary costs — for extra staff, personal protective equipment, diagnostic testing, distance-learning equipment and services, and disinfecting classrooms, for starters — that may be necessary to reopen.

Newsom’s budget specifies no new funding for such expenses; absent more federal relief, it also would reduce current spending for schools via Proposition 98, the landmark 1988 initiative that adjusts support for schools to overall state revenues.

“Across the state, public schools are tasked with the daunting challenge of doing much, much more with far less, educating and supporting students in entirely new ways while protecting the health of the entire school community,” said Laura Capps, president of the Santa Barbara Unified School District board.

Cuts would fall heavily on the majority of California districts, which the state funds directly, under the Local Control Funding Formula; so-called “Basic Aid” districts, including Santa Barbara Unified, Carpinteria Unified, Cold Spring Elementary, Goleta Union, Hope Elementary, and Montecito Union, are financed primarily by local property taxes and would be hit less hard, at least in the short term.

“Luckily, because our funding levels are determined by property taxes, Santa Barbara public schools are not as impacted by state cuts,” Capps said, “although a fiscally conservative approach will serve us well as we navigate these uncharted waters.”