Holocaust Survivors Share Stories With At-Risk Youth

Hope to Inspire Potential Gang Members to Choose a Different Life

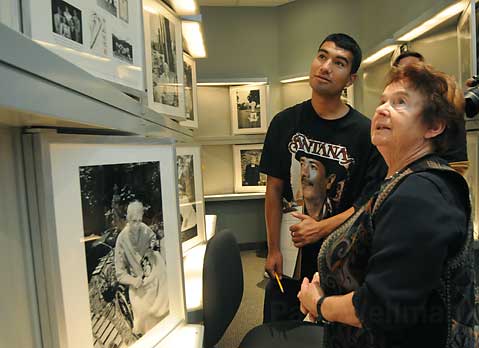

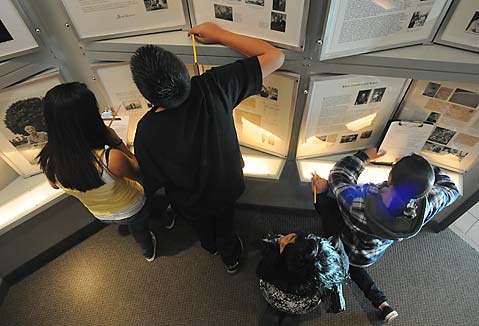

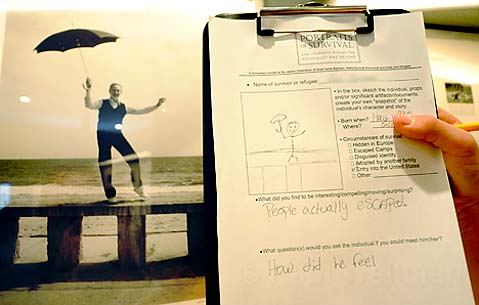

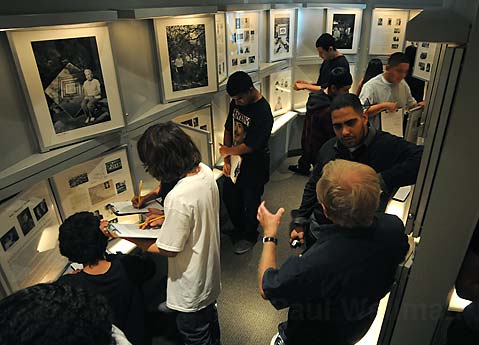

Two Holocaust survivors shared their stories with at-risk eighth-graders from Community Day School at downtown Santa Barbara’s Bronfman Jewish Family Center on Friday in an effort to convey the notion that people can persevere through even the grimmest of circumstances. The students also visited the center’s Portraits of Survival exhibit, which portrays the life journeys of Holocaust survivors.

“This is just storytelling, and it works better than anything else,” said Ross Payson, the educational outreach coordinator for Portraits of Survival.

The students are involved in the Collaborative Communities Foundation‘s Palabra program, which organized the event. They sat attentively through a film about the Holocaust and, following that, stories from survivors Maria Segal and Stan Ostern.

Palabra is run by J.C. Herreda and his brother J.P., two organizers who call themselves “self-educators.” The program takes its name from the Spanish word for “word,” which J.P. explained as referring to one’s word as a man, one’s honor. The Herreda brothers meet with different at-risk groups in the Santa Barbara and Goleta communities twice a week, both at schools and outside them. Every high school has a Palabra program, as do many of the junior high schools. The program’s curriculum has groups discussing different topics every week ranging from gang violence and drugs to law enforcement and knowing your rights. The brothers also hold one-on-one talks with the kids, who are encouraged to call them at any time to talk.

J.P. said they recruit kids by approaching them in their neighborhoods. “The first thing out of their mouth is, ‘Where are you from?'” he said. He said he is upfront with the kids, explaining that he is a former Goleta gang member. “All I have to offer you is knowledge and a different way of thinking,” J.P. will say. He said he has seen how much a person can achieve if he leaves a gang and, as a result, encourages kids to find an altenative to the gang lifestyle.

J.P. emphasized that a majority of the kids involved in Palabra are not gangbangers, but that systems such as school and law enforcement often assume that they are as a result of where they live, how they dress, and whom they talk to.

Segal and Ostern – Santa Barbara residents profiled in the Portraits of Survival exhibit – spoke to the attendees about their childhoods in Europe during World War II. Segal was five years old when the war broke out. She described how Hitler’s “final solution” resulted in the establishment of ghettos and concentration camps, and how her immediate family was moved to Poland’s Warsaw ghetto, after which she never saw her extended family again. She continued on to explain how Germany was very bad economically at the time, and how they blamed the Jews.

Segal’s story involved many instances of people risking their lives to help her avoid capture by the Nazis. She noted that there are good people in the world. She said her hope is that young people will learn to tolerate each other.

Ostern recalled how he survived the Holocaust by hiding out in an underground bunker, because children under 15 who couldn’t work at the concentration camps were sent to the gas chambers. Only 300 out of 12,000 Jews survived from where he lived in Poland. He explained that the Germans needed a scapegoat, and therefore targeted the Jews.

Ostern described the resettlement of Jews in ghettos, built for the purpose of transferring them to concentration camps. He was smuggled out of the ghetto by an uncle who worked on a clean-up crew. He then secretly made his way to a bunker that was built for 15 people, and ended up housing 35. The bunker was located under a house, where a man named Mr. Morgan lived. He emphasized that one good person can make a difference.

Ostern lived in the bunker from the time he was seven years old until he was nine. He had no books and therefore could not learn. The bunker was lit by gas lanterns, making it very hot. The communal bathroom consisted of a hole in the ground. Their “pets” were the huge rats that also lived in the bunker. He mentioned that while the rats could go outside if they wished, he could not.

He was liberated in 1944. He returned to school, going into third grade at age 11, graduating at 17, and finally becoming a doctor. Ostern encouraged the students to think about making the world a better place on an everyday basis, in whatever small ways they can. He added that although the world can seem cold-hearted, there were nonetheless strangers who risked their lives and the lives of their families to help him survive. “Don’t let anyone tell you one person can’t make a difference,” he said.

J.P. said that the students were amazed by the stories, hearing about the Holocaust from people who actually lived it rather than learning about it in a book.