The Boiling Point of Carp Water

Federal Standards Tighten, Costs Increase, and Rates Soar

Facing a possible increase to their already high water rates, Carpinteria Valley Water District customers appear to have put their collective foot down. Based upon their right to oppose new taxes by petition as provided by Proposition 218, a group calling itself Carpinteria H2O put an ad in the Coastal View News last week encouraging water bill payers to help end water rates that they say are the highest in the nation. A monthly bill for 20 HCF (hundred cubic feet)-a fairly conservative use estimate for a single household-costs approximately $142 in Carpinteria, once service charges are factored in, compared to $109 in Montecito and $102 in Goleta.

The district moved the location of its planned May 27 public hearing regarding the rate increase from its normal venue to Carpinteria City Hall in anticipation of a crowded meeting. “We want the Water District to know that we have tremendous concerns over their capital improvements and the fact that they bought too much State Water,” said Vera Benson, one of the group’s leaders.

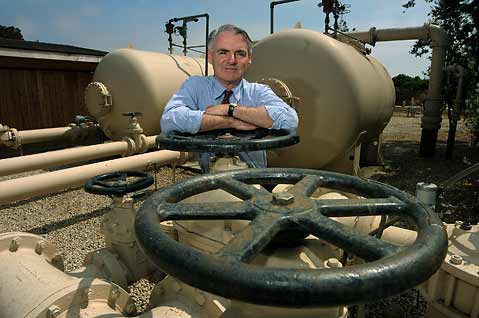

According to the district’s general manager, Charles Hamilton, as well as many of the dissatisfied customers themselves, the problem is rooted in Carpinteria’s State Water Project allotment and several costly capital improvement projects. After Santa Barbara County experienced severe droughts in the late 1980s, the district’s Board of Directors decided that, based upon projected growth and readings of the groundwater table, they needed an allotment of 2,700 acre-feet per year. That was the number approved by voters in 1991, although the district eventually went with a slightly lower allotment of 2,000 acre-feet per year. Hamilton said the decided-upon amount is still twice what the district needs. Current growth projections anticipate less development than what was planned for in the early ’90s. Some customers, however, accuse the district of having waged a public relations campaign that bamboozled them into approving more State Water than was necessary.

Whatever the reason for the decision to purchase the large allotment, the result has been an excess of State Water that the district has been trying frantically to sell. A deal with Plains Exploration Company (PXP)-the oil company that had plans to develop a large parcel near Lompoc-to buy the water for residential use fell through when PXP struck a deal with the Environmental Defense Center and other environmental organizations last year, intending to put most of the company’s land into permanent conservation easement in exchange for expanded offshore oil production rights. The deal was shot down by the State Lands Commission earlier this year, but PXP has not indicated whether it will reconsider its residential development plan. The resulting uncertainty has meant that PXP is no longer paying the district $300,000 per year to hold an option on a significant chunk of the district’s state water surplus.

“The big elephant in the room is that if we don’t get reimbursed [$700,000] by the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services for the Zaca Fire [for water quality improvements at Lake Cachuma], we’ll have to redo the budget,” said Hamilton, noting the district shares maintenance costs with other districts for the Cater Treatment Plant and the South Coast Conduit, the latter of which is a pipeline carrying water from Lake Cachuma.

The capital improvement projects undertaken by the district during the past several years-the cost of which has been passed on to customers through service charges-have been necessary to meet federally mandated drinking water standards, said Hamilton. Projects such as covering the Ortega and Carpinteria reservoirs and construction of a three-million-gallon underground storage tank-which Hamilton said blends pure groundwater with Cachuma water that has picked up organic material on its trip from Cater to Carpinteria-have been contentious due to the fact that they cost, altogether, nearly $28 million. “If you have an uncovered reservoir, you have to cover it. If you don’t have a storage tank, you gotta get one,” Hamilton said, explaining that the water in uncovered reservoirs can allow organic material to combine with chlorine and created a carcinogenic byproduct.

Perhaps the most controversial capital improvement project has been the three-million-gallon underground water-storage tank at Rancho Monte Allegre, a spot in the Carpinteria foothills that had been slated for development of upper-end homes. In the resulting land use deal, the district purchased a 10-acre parcel on the property, upon which the tank was installed. In return, the district agreed to annex 2,150 acres of the 3,400-acre Rancho Monte Allegre to service new development there. As a stipulation, Rancho Monte Allegre agreed to withdraw its petition to the State Water Resources Control Board to divert local creeks-a move that had prompted the district to file a formal objection-relying instead upon water service from the district.

The issue of legal representation became a sticking point when Chip Wullbrandt-a Carpinteria Valley native who has been Carp Water District’s general counsel since 1993-represented Rancho Monte Allegre on what he called an unrelated setup of a conservation easement. Several district customers called foul, charging Wullbrandt with a conflict of interest, but he has been adamant that he worked on the land use issue after the land swap and annexation had already been set up by Susan Petrovich, a Hatch & Parent attorney who represented the landowner in the deal. “I keep getting tarred with this conflict-of-interest brush,” said Wullbrandt, pointing out that a 2007 grand jury investigation found no conflict of interest. Even before the investigation took place, Wullbrandt said that he was no longer representing the district on Rancho Monte Allegre-related matters after people began to complain about potential conflicts.

“People smell a rat in Rancho Monte Allegre because [it] sold 10 acres of land to the Carpinteria Valley Water District and they think that the three-million-gallon tank at Rancho Monte Allegre is so that they’ll have water there [to service the development],” said Benson. Hamilton and Wullbrandt assert that the tank was necessary for maintaining water quality standards while the construction of covers for the Ortega and Carpinteria reservoirs put each out of service. He also said that during fires, having three million gallons of water in the tank would be handy if something happened to the conduit from Cachuma. “That tank has nothing to do with service on the Rancho Monte Allegre property,” said Wullbrandt.

What remains in this dispute is a very tight budget for the district, and high water prices for its customers. With normal maintenance costs and ever more stringent federal drinking water standards looming, the Carpinteria Water District appears to be stuck between a rock and a hard place. “Maintenance still needs to be done, so what do you gain by deferring it?” wondered Hamilton. “What we’re doing is running a bunch of these old valves and mains to failure. That can be very disruptive and costly.” Wullbrandt said that if the district concentrates on maintenance and ignores federal standards, it risks being taken over by a state agency, although the state, too, is strapped for cash. “It’s not the locally elected officials who decide [what water quality standards should be],” he said, “it’s federal regulation promulgated by the state.”

For news on the May 27 meeting, check independent.com/carp.