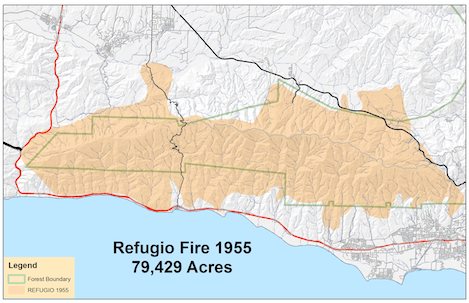

Refugio Fire September 6-15, 1955

79,000+ Acre Fire Ravages Gaviota Coast for 10 Days

“The longer an area remains unburned, the greater becomes its potentiality for fires of uncontrollable fury. The reason is simple. In our very dry climate, the accumulation of combustible debris becomes thicker with each passing year and as the fuel accumulates, the difficulty of quenching a fire also mounts. In other words, sooner or later, flames will spread uncontrollably through the chaparral, and worse yet, the longer between the burns the hotter the fire and the more difficult to control.

Furthermore, by laws of chance, sooner or later one of these fires will break out during Santana weather when temperatures are high, relative humidity is low, and the air is moving anywhere from a few miles an hour to 40-plus miles an hour. Under these conditions, a wildfire grows so monstrous in its intensity, and so great in its coverage, that the combined efforts of Forestry Services, State, County and other local personnel and equipment are completely overwhelmed. A few houses may be saved by concentrating all nearby equipment in a few places but elsewhere the fire burns without hindrance.”

R.B. Cowles

Professor of Biological Science, UCSB

IT IS A THIRSTY LAND. Not because of the water needed by the chaparral – it has long ago adapted its needs to that which is available. It is the city that is parched for water.

In 1900, with a population of barely 6,000, Santa Barbara experiences its first water crisis. The 1890s have been bone dry. Still, the city grows in size. The Southern Pacific Railroad has been completed from Los Angeles in 1891; in 1902 it will be connected through to San Francisco.

Transportation, which has always been a main factor inhibiting Santa Barbara’s growth, no longer is. As the new century dawns the key, as it still is today, is now water. In response to the brewing crisis, the City Council authorizes J.B. Lippincott, who works for the U.S. Geologic Survey, to investigate new sources of water. He recommends construction of a water tunnel from Mission Canyon through the Santa Ynez Mountains to the Santa Ynez River near what is known as the Gibraltar Narrows.

The initial work on the tunnel is begun in 1904 but it is not completed until 1912 due to serious difficulties that include sulphur gas, cave-ins, and quicksand. In 1915 a $590,000 bond is issued and the construction of Gibraltar Dam is authorized and completed in 1921.

Santa Barbara has tied its future to local water to be supplied from the mountain wall, and from a plant cover whose overwhelming necessity is wildfire.

Ironically, the National Forest system is created in 1891, not to protect the majestic Sierras, filled with forests of Jeffrey and yellow pines, but the brush-covered San Bernardino Mountains behind Los Angeles. The Forest Reserve Act is obscure and is attached as a rider to a more important bill, but it serves its purpose well, authorizing the president to set aside land by executive order to protect water flow. All Southern California is feeling the pinch of water.

In 1898, the first local tract, the Pine Mountain-Zaca Lake Forest Reserve, is set aside by President McKinley, and in 1899 the Santa Ynez Forest Reserve is added. In 1908 they are consolidated to become the Santa Barbara National Forest. The main job of this newly created agency is to protect the Santa Ynez watershed from fire, which at the time is considered anathema.

A war on fire is declared.

It is not understood at the time, but the forest and the Forest Service, like the tectonic plates beneath them, are on a collision course.

Despite this declaration, surprisingly, the decade of the 1920s proves to be the most costly in the history of California up to this time. In Los Padres National Forest alone, 495,845 acres burn, an amount equal to one third of the southern portion of the forest.

On September 7, 1932, a butane tank explodes, starting a fire in the Ojai area that burns 219,255 acres. Its west flank escapes into the upper Santa Ynez drainage, decimating a large portion of the watershed above Gibraltar Dam. The Ghost of Matilija haunts those who seek to find the key that will unlock the door of success to fire prevention.

The Forest Service does not seem to be doing its job.

On April 1, 1929, Los Padres National Forest receives its seventh forest supervisor, Stephen Nash-Boulden. Though it is April Fool’s, Nash-Boulden is no trick, and in the 17 years he is in charge of the Forest it is thoroughly modernized. Though he has no formal college education, he is a no-nonsense ranger who expects the most from his employees.

The key to fighting fires, he believes, is attack time, the amount of time between a fire’s starting and personnel arriving on the scene to fight it. In the 1920s this response time is a slow 3.5 hours. Nash-Boulden is determined to change this.

Lookout towers are constructed along each of the main ranges to make spotting fires easier. In the Santa Ynez Mountains, they are located at La Cumbre and Santa Ynez Peaks; in the San Rafaels on West Big Pine and Figueroa Mountains. Nash-Boulden sees that radio telephones are installed in each of them.

Bulldozers and the first mountain fire truck are added, and in the 1930s with an influx of manpower provided by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Forest Supervisor oversees construction of a network of roads throughout the backcountry mountains.

In 1934 he introduces the 10 a.m. Policy:

“Fire suppression will be fast, energetic, thorough, and conducted with a high degree of regard for personal safety ….

“When the first attack fails … organize and activate sufficient strength to control every fire within the first work period; the attack each succeeding day will be planned and executed to obtain control before 10 o’clock the next morning.”

Nash-Boulden, undaunted by sportsmen who are sure to be critical, closes the Gibraltar watershed to the public during months of extreme fire danger except by permit in 1934, and during World War II he closes the Forest to public use entirely.

His efforts are successful. Between 1916 and 1933, there are 40 fires in the Gibraltar watershed which burn a total of 155,712 acres. From 1933 to the end of his tenure there are no more. The key, it appears, has been found, the door unlocked.

Dues must be paid, however. A price has been extracted for that success. Since the fires of the 1920s, brush on the mountain wall has been accumulating. It is now senescent.

THE WEATHER DURING THE PREVIOUS WEEK had been extreme. Temperatures as high as 110 degrees had been registered with humidity as low as 6 percent. Moisture in the chaparral surrounding La Chirpa Ranch near Refugio Pass, critical to the ease with which the vegetation would ignite, had been driven to lows of less than 5 percent.

This trend had started on August 28, the cumulative effect of which had been to make fire conditions in the Santa Ynez Mountains the worst of the decade.

Vegetation surrounding the ranch had been inspected by Forest Service personnel in June and it was noted that, other than the minor cleanup of scattered leaves, a good job had been done of preparing for the summer fire season. Unfortunately, not as much care had been taken with the buildings surrounding the ranch.

Though cooler at midnight, an hour before the fire started, the temperature still remained at 80 degrees. Winds gusted from 15-20 miles per hour. All that was needed was a spark.

The small building in which the fire began was small, housing a generator that provided power for the ranch. Inside were other assorted supplies and an open-topped gasoline tank from which fumes were escaping. An improvised set of wires arced, thus creating the spark that ignited the gas fumes at 1 a.m., early in the morning on Tuesday, September 6, 1955.

At first the ranch caretaker attempts to put the fire out, but in his excitement the efforts are ineffective. At 1:06 a.m., he runs to the main ranch and calls long distance to the phone operator who forwards his call to the Santa Barbara County Fire Department, which receives it at 1:14 am. Immediately units are dispatched from the Goleta and Jonata stations along with one of its commanders, Chief Wadleigh.

Driving rapidly down Highway 101, when Wadleigh first comes into view of the fire he realizes it is inside Forest boundaries and radios the Cachuma fire station to get Forest Service personnel rolling. The Santa Ynez Lookout is notified by the station, which in turn notifies the Los Prietos Ranger Station that a major fire has broken out near the summit of Refugio Pass, but because of the delay in notification, valuable minutes are lost.

At 1:30 a.m., more than a half hour after the fire’s start, Santa Barbara Ranger District resources are on the way from Los Prietos, including all available pumpers, crews, and patrolmen, along with two dozers. The first of the Forest Service forces reach the ranch at 1:44 a.m., just 14 minutes later, but by then the blaze has already spread to approximately 20 acres in size and is being driven by a 15 mph wind.

The Forest Service is hampered not only by the steep terrain, heavy brush, and the critical weather pattern, but the fact that key personnel are out of the county on several other major fires. In the early morning hours, as the fire spreads rapidly, there is a clear realization that gaining control of this fire will be tough.

Though no one yet realizes it, the Refugio Fire, as it will soon be called, will burn for 10 days, consume more than 77,000 acres of vegetation, scar the entire length of the Santa Ynez Mountains from Refugio to San Marcos Pass, and call for a drastic reorientation of fire policy.

Rugged and remote, despite its being near the coast, the western portion of the Santa Ynez Mountains contains more wild country than many legally defined wildernesses. For 20 miles these mountains remain unbroken by roads, and the numerous ranches and small farms to be found along the coast from Goleta to Gaviota form a band of private property that makes access even by foot extremely difficult. Isolated from human intrusion, they form a visual backdrop that is seen daily, though rarely, if ever, have they attracted much attention before.

The sun has beaten down on the chaparral-covered slopes for many days now, and despite how well they are adapted to such conditions, even the hardiest of these plants are being scorched.

From above, the canopy, though dull in color, seems green and surprisingly alive. It is what is below, what cannot be seen through casual observation, however, that is of critical importance.

Meshed and tangled, the plant cover near Refugio Pass is composed of thick, interlocking branches, mostly dead material, that clog the understory and make passage through it almost impossible. The shrubbery is not more than 10-15 feet in height but tons of fuel are contained in it.

The chamise, perfectly adapted to this environment, catches fire first; its small needle-like leaves are filled with creosote. The leaves not only resist evapo-transpiration and are well adapted to fire, but when dropped onto the ground by the plant they react with the soil to form a chemical barrier called allelopathy, that keeps other chaparral plants from invading their territory and allow them to grow together in large communities.

Thick clouds of black oily smoke begin to roll into the sky from the hundreds of acres of chamise. The heat radiates outward, gradually increasing in temperature until the effect is like that of opening a thousand oven doors at once. The heat pours out, searing the brush.

At first the wildfire moves slowly, but as the wind directs its path the front begins to advance more quickly. The intense heat drives off the remaining moisture in the tiny leaves and small diameter branches of the ceanothus, which are next to burn, converting them to flammable gases which burst into flame as the front ignites it.

Next the manzanita, their beautiful shiny smooth bark fiery-red, burst into flame. As the front passes, the heat is not so easily conducted into their thicker cores. The leathery green leaves and smaller outer branches ignite, incinerated into a fine powdery white ash, but the main branches only char. The bushes that remain behind look like glowing orange-and-black fingers that stick out of the ground.

In their glowing state they are beautiful, but their destructive potential remains. The front has passed through this area so quickly that not all of the brush has been burned. The glowing embers from these charred fingers soon scatter in the wind, and what has not yet burned soon will.

The heat, now approaching 1,000 degrees, begins to generate its own wind currents; as the hot air rises, cooler air is drawn in, which is then in turn superheated and funneled along the contours of the steep topography where the radiating heat and superheated winds cause temperatures to rise three and four times over for short periods of time.

In brush that hasn’t known fire in more than 50 years, as the wind orchestrates the front’s path, pushing it toward Santa Ynez Peak which is three miles to the east. The fuel burns readily and intensely, concentrating the radiating heat along steep, almost inaccessible upper headwalls.

Up to this time there has been but one policy for dealing with fire; suppress every one with the utmost vigor. Fire is the enemy; one which must be dealt with severely and swiftly.

It is not yet understood that the chaparral needs fire to remain healthy as surely as the animals that inhabit it need food and water. Over millions of years an equilibrium has been reached; in a Mediterranean climate such as ours, fire has become the most efficient means through which the chaparral can be decomposed.

The cycle in this brush is perhaps 25-30 years in length, meaning that the Refugio chaparral is overripe. This chaparral has matured prior to the turn of the century; since the early 1900s, it has been producing yearly increments of dead material and over time the ratio of dead fuel to live plant material has increased dramatically. As the fire burns toward it, as much as 50 percent of the standing mass of the chaparral is dead, and thick beds of dry material litters the ground. Thus prepared, it awaits the flames.

The relationship is both curious and ambivalent. Fire is among man’s oldest and best used friends; but as man has expanded the boundaries of his suburban homes and become more dependent on the back country for needed resources, in its most primitive and uncontrolled state, wildfire has also become terrifying and terribly destructive.

It seems a Catch-22 situation.

To protect vital resources, the threat of wildfire must be eliminated; to do so in chaparral country almost seems to guarantee that they will occur. Given an appropriate mixture of fuel, heat, and wind – which occurs regularly in chaparral ecosystems – when they do occur they become large, uncontrollable, and expensive.

But on the morning of the 6th, firefighters are not asking themselves philosophical questions; these will come later. The immediate efforts are to contain the fire to the east, or Santa Barbara, side of Refugio Road and the south, or ocean, side of Camino Cielo. By 8 a.m. the fire has not only spread east but also rapidly down into Refugio Canyon, threatening guests at the Circle Bar B Guest Ranch and other nearby structures, having consumed more than 1,200 acres of chaparral.

Firefighting forces concentrate just above the ranch and, along with heavy use of the pumpers, are able to stop it just short of the main buildings, though not before destroying two outlying guest cottages. One of these, “The Hideaway,” is occupied by Carl Wiggins and his wife, newlyweds, married only Saturday. They are forced to flee in the face of the advancing flames.

At a nearby ranch, the Dal Pozzo family has slept peacefully until just before dawn when the deep-toned bark of Gustav, their great dane awakens them to the danger. At first the threat seems far away, but as the morning hours pass, the fire nears. Shortly after noon, the danger, which had heretofore seemed close though not too fearful, becomes very real.

“You can hear the roar of the fire distinctly,” reports Frank Clarvoe, News-Press associate editor, who is on the scene. “From the window of the Dal Pozzo home, I have a visual range of 180 degrees. All the way around this half circle, flames are moving up and down the slopes and through the dry grass, brush, and scrub oak in an unbroken line.

“There is a rain of ash. There are several layers of deep brown smoke, and the whole sky is cut off. The cloud of smoke driving out over the ocean makes the sea appear from here to be almost brown in color.

“The Edison Co. has cut off its lines up the canyon.

“The women around the ranch here are using hoses to dampen things down. The fire is on the ridge just above them …

“The smoke is mushrooming up in varying colors, and the sunlight is reduced to an amber glow. The whole side of the mountains is an eerie kaleidoscope of colors.”

The fire continues inexorably down the mountain, at one point encircling the house in flame, but because the women have dampened the buildings and surrounding vegetation with water, the ranch is saved.

As the fire races down slope it passes the Circle Bar B Ranch, where at noon, the guests lounge about in the yard, thinking the fire no longer threatens them. But in the lower foothills, the front surges westward as the wind gusts, cutting off Refugio Road from beneath them, and for a few minutes there is panic, their only possible route of escape over Refugio Pass where the charred remains are still aflame. But quickly the danger passes.

At 6 p.m. the fire leaps across Refugio Road and begins to eat up hillsides filled with grass and coastal sage on the west side of the road. The sage explodes into flame, crackling, the terpenes in the aromatic leaves burning almost as explosively as gasoline. The front has split, now spreading outward both to the east and west, moving relentlessly across the foothills in either direction.

“The sun, when one could see it was a hot, deep red disc,” Clarvoe continues, as he describes the rapidly expanding pace of the fire.

“The wind was hot, and seemed to blow from many directions at once, bringing with it the heat of the fire as if an oven had been opened. The wind was laden with ash, and sometimes it lifted embers from the front of the advancing flame line, hurled them thousands of feet to start new fires.

“Along the ground the wind whipped up dirt and sand, and soon one was covered with sweat and ash and dirt.”

“And the heat – always the heat, from the seared and searing patches of scrub oak and dried grass.

“Such was the fire in all its sinister majesty, its terrible beauty.”

By 7 p.m. on the western flank, high winds in Tajiguas Canyon, funnelled seaward from smaller canyons on either side, send searing jets of flames clear across the highway. Semi-trucks, many of them loaded with perishables destined for markets in Santa Barbara, line the now deserted four-lane road. The Highway Patrol has halted all eastbound traffic. Nor is there northbound traffic, save for a caravan of vacationers requesting evacuation from Refugio State Beach who are escorted through the choking smoke.

On the deserted highway, two cars emerge from the chaos, slowly herding 15 head of cattle. A wall of flame spooks the cattle and for a frightening moment they jam themselves against a barbed wire fence on the opposite side of the road trying to escape the fiery wall. Two ranchers emerge from a group of spectators who are watching the fire advance toward them. The men climb a ridge to where the cattle are huddled and cut the wire. The crowd cheers. Thousands of other animals will not be so lucky.

By 7:45 p.m. the fire has surged another several miles to a ridgeline overlooking Arroyo Hondo Canyon. At this point, things look extremely grim on this edge of the fire, now less than five miles from Gaviota and still moving.

The main worry, however, is on the eastern front that is pressing inexorably towards Goleta. Fortunately, out-of-town Forest Service personnel begin to arrive on the scene, one of them Nolan O’Neal, fire control officer for Los Padres, who immediately orders the establishment of fire camps at Refugio Pass, San Marcos summit, and the Serra Ranch in the foothills above Fairview Avenue in Goleta.

“The fire remains very critical,” he announces, “with no change in weather predicted for the next two days.” Hoping to calm the growing fears, he adds, “Every effort is being made to check the fire, with major emphasis on the east end of the fire” and that “every possible assistance is being given to adjacent ranch property owners.”

Thus far the fire has followed an extremely frustrating pattern for firefighters. Racing eastward toward Santa Barbara it has stayed along the higher mountainsides and above the roads that serve ranches and farms along the coastal plain where it is extremely difficult to fight, and then, after having outraced the efforts of those fighting it, it has burned in multiple heads down into the canyons where these ranches and farms are situated, diverting precious fire personnel to the protection of these structures.

To combat the wall of flame that is burning across the upper slopes, on the afternoon of the 6th, backfires are set along the crest of the Santa Ynez Mountains from Refugio Pass to Santa Ynez Peak in a massive attempt to keep the fire on the south side of the mountains.

At the same time, in an attempt to outflank it on the east, dozer crews are quickly trucked from Highway 154 across West Camino Cielo to the head of Tecolote Canyon to open up a line from the top of the mountains down to Highway 101 from which a stand can be made. Additional cats work their way up the steep ridgeline toward Condor Point to join this line.

High temperatures and low humidity add to the difficulty of fighting the Refugio Fire. At midday the temperature is 98 degrees and though it has lowered to 84 degrees by 6 p.m., Sundowner conditions cause it to soar again to 88 degrees by 9 p.m.

The line being cleared by the dozers has been started five miles in advance of the fire, enough of a buffer for firefighters to dig in and stop most fires, but this one surges, running eastward at the speed of a fleeing deer, allowing it to breech the dozer line easily. During the remainder of the night, the fire steadily advances across Tecolote and Winchester canyons.

“From up above at 2 p.m., the force of the fire was increased with the rising gale,” the News-Press reports. “The howl of the wind and the deep roar of the flames, like a speeding freight train combined in terrible symphony. A county fireman high above abandoned his backfiring torch and moved down ahead of the flames, helpless to check them …

“The ground came alive. Brown rabbits and deeper-brown field rats ran zig-zag courses to escape the terror … Up above the canyon across the road from the house, a big owl, light gray in the glow of the flames, flew leisurely – toward the fire – concerned, perhaps, about her nest.”

The vegetation is being eaten up at a ferocious pace. For as much as 10 miles along Highway 101, the land on both sides is aflame. Thousands of railroad ties catch fire and the thick, oily smoke pours upward and over the ocean.

By 8 p.m. the evening of the 6th, 22,000 acres have been scorched; 24 hours later that total has risen to 40,000 acres. In less than 30 hours the fire has blackened the entire coastal side of the Santa Ynez Mountains from Gaviota to Glen Annie Canyon, a distance of almost 25 miles.

It has been remarkably fortunate that few structures have been lost; this is due primarily to the fact that the fire has burned land that is remote and little inhabited. But dawn approaches on the 7th; the Refugio Fire is now on the edge of civilization.

For the first time in what is normally a quiet tourist town for most Santa Barbarans, the raw power of the fire menaces them directly.

Early in the morning of the 7th, a second dozer line is cut down a ridge line between San Pedro and San Jose Creeks and is completed by mid-morning. Thus far the fire has made less headway than yesterday or the previous night and has entered a period of lull.

Three hundred weary men hope the period is not temporary. They are joined by 400 fresh troops, raising hopes further, with 200 more on the way, including trained firefighters from Colorado and New Mexico.

But just as the fuel break is being widened enough to backfire, the winds kick up and the fire, which has lain down most of the morning, begins an eastward run that crosses the dozer line near the base of the mountains.

The Santa Ynez Mountains have become a war zone. Steadily the flaming enemy advances and the troops fall back, unable to gain enough of a foothold to make a stand. They retreat once more, this time to Old San Marcos Pass Road.

This is a line they cannot afford to lose.

“What we need is a direct pipeline to the weatherman,” fire officer Nolan O’Neal laments, after losing the second dozer line between San Pedro and San Jose Creeks. “He is more important than all of us put together.” But the weatherman does not seem to be listening.

News that the fire has also surged up and over the mountain crest near Santa Ynez Peak worsens the situation. Thus far, the fire has blackened the entire front side of the range west of Highway 154 and now the back side of the Santa Ynez Mountains is in danger of being lost.

The slop over is picked up on the western edge of the breakthrough near Tequepis Canyon by crews manned from an old CCC camp near Refugio Pass. On the eastern flank the fire begins a run toward Highway 154 in the vicinity of Cold Spring Tavern. Quickly forces are massed to construct lines down the north slope to cut this flank off.

Near Gaviota, also the morning of the 7th, the news is better. Dozer crews clear the crest from Refugio Pass to above Arroyo Hondo hoping to get a handle there before the lull ends. Frantically the ridge is backfired. The intentionally set fire moves slowly coastward to meet the advancing wildfire, and for the moment these crews are able to hold their ground, and keep the front from moving north over the Santa Ynez Mountains.

The wide expanse of San Jose Canyon is all that separates the fire from Old San Marcos Pass Road now.

Earlier, with hand crews starting from the bottom of San Jose Canyon, and dozers blading a wide path from West Camino Cielo along the ridgeline just west of the Trout Club, a line had been tied together by midday on the 8th, but like the other lines it is lost, too, when afternoon winds again cause the fire to surge.

For the distance of a mile, it roars through heavy brush in less than 15 minutes, fanning out and throwing spot fires ahead of itself. Catching fire personnel by surprise, the fire not only jumps Old San Marcos Pass Road into Maria Ygnacio Canyon, but runs over the crest of West Camino Cielo near the Winchester Gun Club and down into the upper watersheds of Bear and Hot Springs Canyon, creating a second front on the north slopes of the Santa Ynez Mountains.

At this point a strategic decision is made to abandon the Gaviota line; all forces are needed on the eastern edge of the fire where residences at the San Marcos Trout Club are in danger. Only a handful of county firemen under the leadership of Chief Wadleigh are left behind to protect structures in that area. The fire burns unchecked on the hills.

Forces mass on Highway 154, the greatest concentration of manpower since the fire has begun. Fifteen pumpers arrive from Los Angeles and rush to the pass, where they form a line from the summit down to a point near the Trout Club.

There are 1,274 fire fighters involved in the action now, along with 500 Marines with full equipment enabling them to maintain themselves as a separate unit, more than 40 pumpers and 17 bulldozers, and two helicopters that are coordinating the operation from the air.

By this time the fire has burned more than 68,000 acres in just slightly under two-and-a-half days and covers a 65-mile perimeter.

Throughout the night the fate of the Trout Club residences hangs in the balance. The situation is tenuous. Erratic winds cause the fire to shift quickly and at several points men and equipment are evacuated for fear that they would be trapped.

“I’d rather be back in Prescott, this is a tough one,” an expert who’s been flown in from Prescott National Forest exclaims as he views the situation.

A hundred yards below the last Trout Club building, 27 Native American firefighters mass in an area that is impossible to backfire. They have been used by the Forest Service since 1950.

The Native Americans, from eight different tribes, have been flown in from Albuquerque, arriving on the scene of the fire early in the morning. They have been greeted warmly. “Here come the hard hats!” the other firefighters shout, knowing they now have an ally on their side they can count on.

The Mescalero Apache can be identified by their shiny red helmets. Others have silver ones labelling them as Zuni, Zia, or Taos Indians. The hard hats worn by the Indian firefighters are greatly prized and decorated so that anyone knowing the crew’s insignia can tell where they are from. Jemez Pueblo Indians sport an eagle with outstretched claws; the Cochiti’s symbol is the green fir tree; and the Zia sun marks theirs.

Used to the semi-arid conditions of the Southwest and accustomed to traveling in rough country, they know how to take care of themselves in the extreme heat. Working without water or backfires, they fight hand-to-hand, using only shovels and other fire tools for weapons.

They are traditionally farmers, growing corn, beans, and squash, as well as raising cattle and sheep on their reservations when they are not fighting fires. In their pueblos or reservations, they are organized under a clan form of government which lends itself to working as a team rather than as unorganized individuals.

In between the long 12-14 hour days of fighting fire, the Native Americans rest, eat, play their simple Indian games, and sing the old songs and chants that were ancient when the first white man arrived in the Southwest.

Now the Indians ready themselves for the flames, which are licking their way up San Jose Canyon, here now to help the white man fight what they call the terrible red wolf.

They are paid well on the fire lines – $1.75 an hour – and they fight fiercely.

On Old San Marcos Pass, just below the first switchback, another crew of Forest Service men build a hand line down toward the Indians, hoping to isolate the Trout Club from the blaze, which is roaring in the canyon just below them.

They are successful in protecting the houses.

“By gosh,” Rudolfo Lopez, a Zuni, says shyly afterward, “the fire was pretty close.

“But we stopped it only a few hundred yards from the houses,” he adds proudly.

Residents of the Trout Club later tell a reporter, “There was a pumper on every corner or hilltop and an Indian behind every unburned bush; we were never so well guarded in all our lives.”

Shortly afterward, the slopover in Maria Ygnacio Canyon is picked up. For the first time it appears that the eastern flank of the Refugio Fire is under control.

“I have often wondered what it would be like to be alone in the world,” Bill Hilton thought, as he returned to his Trout Club residence. “Last night I discovered that being alone is something to be avoided. Last night I moved my family back into the San Marcos Trout Club and we spent the night there.

“To be sure, we were not alone. But when we looked out our windows, we could not see the usual lights from neighbors’ houses nor hear the usual chatter of children and barking of dogs.

“From our window we could still see flames and embers on the hillsides across San Jose Creek from the Trout Club.

“In the lulls between making up beds for the children and cleaning the ashes and dust from inside the house, we could hear rocks, loosened by the fire, rumble down the hillside across the canyon.

“Then late in the evening, after all the lights had been turned out, the coyotes and foxes, evacuees themselves from the fire-blackened area, set up a howling symphony unlike anything heard in the Trout Club before.”

Stubbornly, the Refugio Fire lasts six more days, though no longer threatening the front country.

The Gaviota front is contained by construction of a fuel break six-to-seven blades wide cut from the Gaviota Tunnel to the top of the Nojoqui grade, down in back of Nojoqui Park, and through grassland and oak forests to a point behind Alisal Ranch where it is tied into a line established from Refugio Pass.

On the north side of the Santa Ynez Mountains numerous lines are cut across its flanks from the crest down to Highway 154, dividing the numerous slop overs into smaller portions that favor firefighters.

On the 13th, the fire makes one last determined effort to break through fire lines. Fresh breezes fan flames that leap across Highway 154 near Rosario Park, which has been evacuated, and crosses the Santa Ynez River near Paradise Road and heads towards the San Rafael Mountains. But this is grassland and is more easily controlled than that in the chaparral.

Flames burn on three sides of the Paradise Store but it, too, is saved. The breeze lays down and the weather now favors firefighters rather than the fire. Nolan O’Neal has gotten his wish – the pipeline to the weatherman has been established.

On the 15th, at 3 p.m., 10 days after it has begun, the Refugio Fire has been contained, Los Padres Forest Service announces.

ON THE 19TH, at the summit of San Marcos Pass, in the sliver of a new moon glimmering overhead, a celebration is held. Amid the chants and drumbeats of dancing Indians and the happy smiles and shouts of nearby mountain residents, the eight tribes of Indians who have fought so bravely are staging their traditional “Rain Dance.” It is time to celebrate, to relax now that the blaze they’ve been fighting is brought under control.

The fire is over.

NOT EVERYONE IS HAPPY. “Do you suppose this fire will change the official Forest Service attitude on controlled burning?” one man shouts afterward.

“Look here, if we in Santa Barbara allowed our weeds and old papers and other flammable trash to accumulate year after year, all around the house and the yard and the garage – if we were foolish enough to do that we’d have a helluva blaze on our hands once things did catch fire.”

Many conservationists grumble. Ranchers on both sides of the mountains whose lands have been threatened or destroyed by the fire demand action.

The Forest Service finds itself in a difficult situation. The brush in most of the front and back country is now too clogged with dead material to consider the use of controlled burns anywhere save what has burned in the fire. Fuel breaks that might break up the chaparral into more manageable blocks are almost nonexistent. The cost of fire suppression is rising drastically.

And the people are angry.

For more than 50 years they have demanded protection from fire; now they demand, equally insistently, that fire be returned to the landscape.

_______________________________________

Author’s Note

This is the first in a series of stories that chronicle Santa Barbara County’s wildfire history over the past half century. These stories were first published as a part of my 1990 book entitled Santa Barbara Wildfires.

Today, there is a great deal of controversy regarding prescribed burning, fuel breaks, vegetative type conversion and especially, if and/or how chaparral is or isn’t adapted to wildfire. One thing remains certain as the values at risk when wildfires such as the recent Gap, Tea or Jesusita fires hit our community is that the most effective way to deal with wildfire isn’t by focusing on the chaparral but the homeowners who choose to live in harm’s way.