Q&A with Greg Mortenson

Three Cups of Tea Author to Speak at the Arlington

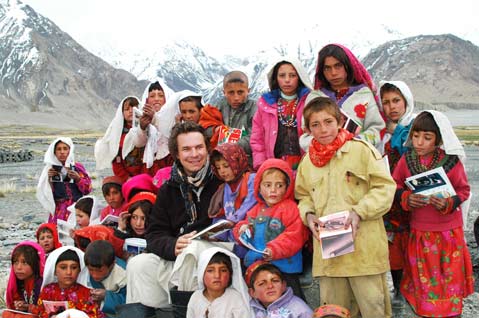

In 1993, during an attempt to climb the world’s second highest mountain K2, Greg Mortenson stumbled into a picturesque Pakistani village. To make a long story short, he has been building schools for girls in the remote rural regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan ever since. Mortenson’s best-selling, adventure-packed books about these experiences are now required reading for U.S. military personnel. His latest, Stones into Schools, picks up where Three Cups of Tea left off: with his acceptance of a personal invitation from Khirgiz horsemen to build a school in northeastern Afghanistan, the heart of Taliban country.

On Tuesday, May 4, Mortenson will speak at the Arlington Theatre. His recent interview with The Independent provides a taste of the natural diplomacy that has made his Central Asia Institute’s efforts so successful; to date, they’ve built 130 schools.

Do you have problems with the Taliban?

Well, none of our schools have been destroyed or shut down by the Taliban. We have had altercations with the Taliban, but also we meet with some of the Taliban. You know, the CIA once asked me, “How many of your parents are terrorists?” Craziest question I ever heard. It’s like “How many students in all the Santa Barbara School District are misdemeanors or felons?”

There are the older Taliban, who are a little more ideological; they want to set up a country under Sharia law. Then there are the new Taliban—I call them the neo-Taliban. They’re getting much less funding from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, and they’ve become much more criminal and more Mafia-like. They do more extortion, heroin trafficking, and illicit lumber trafficking. And they’re brutalizing the people, they’re going in at gunpoint often and saying, “You need to give us 20 young men for soldiers, we need dishwashers, we need one goat a day, we need this and that.”

Another thing I’ve noticed is that the suicide bombings have gone way up in the past two years, but most of the suicide bombers—these are the walking bombers—they’re often the physically handicapped, the four, fifth, sixth, or seventh sons, who are kind of marginalized already; they’re not going to get inheritance. They take them sometimes at a young age, they isolate them, drug them, beat them; they rape them, they program them, and so very soon you’ve got a brainwashed kid. And when they put on a suicide jacket they actually sew it on them they so they can’t take it off. So they don’t really have a choice.

How do you know this?

I work in these real rural areas. We’re working where the Taliban roams.

Do you know where Osama bin Laden is?

If I knew that I could get $50 million and build lots of schools.

Is that the price on his head?

I don’t know, $25 or $50 million. If I had to answer that question based on the people I talk to, most people think he’s dead.

What kind of work are you doing with the U.S. military?

On my own I go to about 20 military bases a year and I teach the troops about cultural understanding. For example, when the people there have a dispute, they call it a jirga. Say you and I have a land dispute. The participants in the jirga are generally the elders, and we do not finish the meeting until we resolve the dispute, and if we can’t resolve it we summon more elders, and if we still can’t agree then we agree to fight.

If we agree to fight, then we have to set terms of engagement. And then, the interesting thing is, the victor has to take care of the vanquished widows and orphans for the rest of their lives. So it puts a price on human bloodshed. In the U.S.’s dealings with the tribal people, we’ve never really done it their way.

Do the jirgas have women in them?

Some jirgas have women in them all the time. There’s also the shura. Shura means elder. Every province—and there’s 32 provinces in Afghanistan—every province has, say, five dozen to 20 dozen elders. There’re poets, warriors, businessmen, teachers—not too many women, but they have a very strong voice in the community.

We often stereotype Islamic women as being uniformly under the thumb of oppressive males, but their status probably varies from tribe to tribe, doesn’t it? And of course there is the fact that Pakistan had a female prime minister, the late Benazir Bhutto. So, are you bringing light to peoples who are entirely in the dark, or working with something that already exists?

Obviously there is oppression of women and they are treated like chattel in some areas where the despot mullahs desperately want to keep them illiterate. But I’ve been blessed to get very close with people, so when I get into the households, I find out that generally women run the house; they’re the main decision makers in the house, and the main allocation of resources is decided by the women.

One of the things I’ve seen happen in Afghanistan, as more and more women become literate and also have legal advocacy, is that the number of women you see in the district courts, filing titles for land ownership, is skyrocketing. The Koran itself and even Sharia law are very explicit about the right of landownership for women and widows. Unlike the Torah and the Bible, it actually spells it out. But, you see, the Koran is in Arabic, and 90 percent of people in rural Afghanistan don’t know what it means. So when women can read and write, they know that in their faith it says explicitly that they can go and do that.

There are almost one million widows in Afghanistan. As they return to the country, to their ancestral homes, they find the mullahs there, or the local chief, or squatters, who tell them, “This is not your land.” And then they have to leave and go back to the urban centers of Kabul or Kandahar and get very demeaning positions—they’re either in virtual indenturement, or trafficking, or whatever.

Nowhere to run to.

Even jihad—technically, in the Koran, it means a quest. It can be a spiritual endeavor, it could be academic, it could even be military, but when someone goes on jihad they first need permission from their mother. Even Osama bin Laden asked his mother three times for permission to go on jihad to Afghanistan, but she wouldn’t let him go so he went on his own accord.

Oh, disobedient.

And when women become literate, they are less likely to give their sons permission to do suicide bombings. But it is certainly true that women are marginalized and brutalized too, and it’s so hard to see. In once province where we were working, a woman was stoned to death for adultery. What happened was, her husband left home like eight years ago, so she didn’t have any support, so she moved in with his brother. And some guest came along, and I’m sure there wasn’t any frolicking around or anything but basically because some guy was in the house, they ended up stoning her. They get kids to throw the stones. You know they’re small stones, and they say—

Aaaaw, no. They got the kids to throw the stones?

Yeah, because, you know, like in the Bible, or in the Torah, they say, “You without sin throw the first stone?” Same thing with Islam, so—

So that would be the children.

Yeah. Apparently the family can actually forgive the person, they can let them go, even before an execution, but apparently, they just get these kids worked up and bury her up to the chest and then they cover her head and then they just pelt her. Sometimes it goes on two or three hours.

Did you witness this?

No, but I’ve heard about it. I’ve talked to the kids. You know, there’s a lot of sad things. My wife works at a battered women’s shelter here in the U.S.; she’s a clinical psychiatrist and she volunteers there leading therapy groups. American men who are batterers isolate and marginalize women, and then get them involved in a cycle of dependency, and then they start working them over. It’s the same mentality, really, but in Afghanistan it’s more what I call warrior culture. Since Alexander the Great, for 2000 years, that country has had to fight invading armies—the Mongols, the Greeks, the Timorese, the Russians, the U.S. So it has kind of established a warrior ethos, so in that culture the women are more there to facilitate the men as they fight. There have been periods of peace, but they really haven’t known peace for a very long time.

We go around saying such things as you can’t negotiate with a madman, and so our chief executive will go to war without ever having first sat down and talked like a human being with whomever he’s going to war with. Do you find that disturbing?

Oh I do. You know, I was excited when President Obama was talking about talking to people. At least he talked the talk. In Three Cups of Tea I was fairly critical of the military after 9/11. I even went to the Pentagon and I described them as laptop warriors. I said they had smart bombs but no boots on the ground, and that nobody in the military could even speak Pashto. But today—this is my opinion and some people don’t like to hear this—but I think in many ways the military is ahead of our State Department and our political leaders. Again, I’m pretty much a pacifist, but I’m trying to say what I see: Because many of our soldiers have been on the ground three or four times, some even five times, they really get it that it’s about building relationships, that it’s about empowering the elders and about listening more.

For example, General Stanley McChrystal was appointed last April to be in charge of all the forces in Afghanistan, and one of the first things he did was to ask me—and some other Americans who are working there, including Sarah Chase—to set up a meeting between the elders and the U.S military. There are 32 provinces of Afghanistan, so over the past year we’ve helped facilitate about three dozen meetings between military leaders and the elders, the shura.

And what are they saying?

What the elders are saying is first, please do not bomb and kill civilians. Number two, they’re saying please involve us in the discussions. They feel very marginalized because the U.S. is so busy trying to prop up this fragile, corrupt central government when the elders are really the wisdom and are listened to in the rural areas.

And another thing is, Vice President Joe Biden, and even conservative columnist George Will, are saying to pull troops but do more target-selected bombings. The elders are saying you cannot replace troops with bombings; it’s not going to work.

And even if you do bombings—I’ve talked to military people about this—you need intelligence on the ground. Without intel it’s a totally futile proposition, you just antagonize the people. I’ve spoken several times to Admiral Mike Mullen and General David Petreaus, and Admiral Eric Olsen, the Special Forces commander; and they all say explicitly that there is no military solution in Afghanistan. They say it needs to be much broader, that that the U.S. is putting far too much emphasis on trying to solve the situation militarily.

One of the things I was concerned about was when President Obama decided to deploy 32,000 troops to Afghanistan last November. In order to make that decision—and President Bush did the same thing so I’m not trying to be partisan—but in order to make that decision there were nine meetings held on Capital Hill with military commanders, senators, congressmen, and President Obama, but none of them consulted the shura.

It was only last month—I was very excited—that President Obama actually asked the U.S. military to come and have a two-hour briefing in the White House with the National Security Agency, and the context of it was, what are the elders saying to us? What do they want?

He’s probably read your books.

Well, I don’t know but: Go, Obama! Before this recent Khanjar operation—that’s this huge operation the U.S. military is doing right now in Helmand Province in the south—before the U.S. went in there, General McChrystal met with 420 shura three times, in long meetings, to involve them, to basically plan the operation. I’m not saying the military is the solution, but it’s really interesting that finally they’re involving them. And next month, on May second through the fifth, President Karzai is summoning 1200 shura to Kabul, to advise him.

And will that work, when it’s such a different format than the shura have been used to working in?

Yeah, well, they’ve already been meeting on a smaller scale. Consensus building and—it’s not like this silly bipartisan government where everyone just follows their party line. The shura use a consensus-building process. You keep testing, pushing it until everybody agrees on what is decided. Sometimes it gets really violent, and aggressive, and I think sometimes they’re going to kill each other, but I’m always amazed at how the shura can push through and come up with a really good solution.

Do you see any downside to bringing schools into tribal areas?

The one negative thing about literacy and education it often eradicates the storytelling tradition. Many of these stories are also told by mothers and grandmothers to their daughters and granddaughters in the field while they’re working. When you pull a girl from the field and put her in school, then you’re destroying some of these very precious indigenous traditions, so one of the things we do is we have the elders come into the school two or three times a week and do the storytelling and the songs because we don’t want that to be lost.

What kinds of stories and songs?

Well, many of the different indigenous groups pass on their legends in their ballads. One of them is a story of creation and evolution. It’s a mix of Buddhism, and Islam, and shamanism, because they also have this very rich tradition about little fairies, and snow serpents on top of the mountains who make sure the bad things stay on planet earth. We’ve translated some of these, we’ve recorded them, and I think I can get a copy if you want. They’re very interesting. Go to Mongolia, northern Pakistan, Iran; they all have these ballads.

I don’t know if I mentioned it, but I visit 100 to 120 schools a year in the U.S., both public and private, rural and urban. One of the questions I ask them is how many of you think you have spent at least ten hours talking to your grandparents or elders about the Depression, WWII, Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, etc.? In the U.S., the average is five or maybe ten percent. If I ask that same question in Afghanistan or Pakistan, the answer is between 90 to 100 percent. I think that’s one of the greatest tragedies in the U.S.: that we don’t have that oral tradition.

That brings me to the question of what the classrooms look like. You sort of sprinkle that kind of information throughout Stones Into Schools.

First of all, we have to comply with the government—you have to have history, math and science, writing and reading. We also teach hygiene, sanitation, and nutrition starting in first grade, and not only that but because of the lack of health care in many areas we teach teachers how to screen the students for rickets, vitamin D deficiency, and polio. And by fifth grade our students learn five languages.

Five languages by fifth grade?

Yeah, for example in Pakistan there’s Urdu, Arabic, Pashto, and English, and then they speak their tribal talk, you know there’s very many of them. And then in Afghanistan we switch Urdu for Dari; Dari is the lingua franca of Afghanistan.

Not only do we teach them how to write Arabic and read Arabic, but we teach them how to understand Arabic. That’s where we get—well, in the States people get upset at us, and the mullahs also get upset with us. But when the people understand Arabic they will learn that in the Koran, nothing says that girls can’t go to school. Also, the worst two sins you can commit in Islam are suicide and the killing of civilians.

And also, at the schools, we’ve developed it to where on the weekends and holidays and summer and winter, the students teach the adults reading and writing and literacy, so it becomes a communal thing.

We provide skill, labor, materials, and most of the teacher training, but the community has to provide free wood, free land, and then free manual labor: 5,000 to 8,000 days of free manual labor if they want to get a school built. And then, the money they save on a contract, we match it—say $1,000—and then with that money they set up their own poultry farms, like for chicken and eggs, poplar tree plantations, vocational training centers, or broom making. They put half the money the make on those endeavors into the school, and the other half they put into community micro-credit loaning. I was in Bangladesh for a while and I sort of learned this from the Muhammad Yunus model, you know, the Grameen model. It’s a little bit risky sometimes to give people money to loan out. I know it sounds stingy, but you actually have to help them make money, so then they can loan out that money.

So they’ll be sure to collect?

So it becomes more sustainable and meaningful to them. It also shows them that you can do this on your own; you don’t need a bunch of westerners. It is much slower, and it’s frustrating and methodical, but I think it’s the only way to help people, empower them.

Abrupt change of topic: You first went to Afghanistan to go mountain climbing, and in Stones into Schools at one point you write with great appreciation about the number of stars you can see there. I’m wondering is if any part of your agenda has to do with saving the place for mountaineering or for the nature of it as distinct from development?

That’s great; I never heard that question before. You know, I really think women are the conservators of the earth, women bring life into the world, women nurture life, and women really in many ways are really the conservators of the environment, whether it’s in a village or a nation. This is just my own feeling, and some UCSB scientist is going to throw a book at me, but I feel that there’s some correlation there. In really rural areas, like with pastoral nomadists like the Khirgiz, the men measure their wealth in sheep and goats and yaks, and the women are constantly yelling and beating and complaining at them, like “Go sell it, make some money! Look at this land; it’s almost like a desert now because you’re greedy!”

And another thing—This is a little off of your question but one of our biggest global problems is that there are just too many people on the planet, especially if you look out three to five generations. The number one way to reduce population without doing anything else—nothing controversial, nothing political or legislative—is simply female literacy. The best example is the country of Bangladesh in Southeast Asia. In 1970 the female literacy rate was less than 20 percent and today it’s more than tripled: it’s like 63 percent. In 1970, the average woman had nearly nine births—8.8 births—and today the average women has 2.8 births. They’ve done a lot of studies on it, but it pretty much shows that it had to do with the female literacy rates. So when you talk about preserving the land and the environment and the ecology—as more people flood an area, the inheritance, the land, gets smaller and the people press out into the pristine wilderness.

4•1•1

Greg Mortenson will speak at the Arlington Theatre on Tuesday, May 4 at 8 p.m. For tickets or more information, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.