Drawn to Modernism at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art

Show Puts the Gifts of Wright S. Ludington in the Spotlight

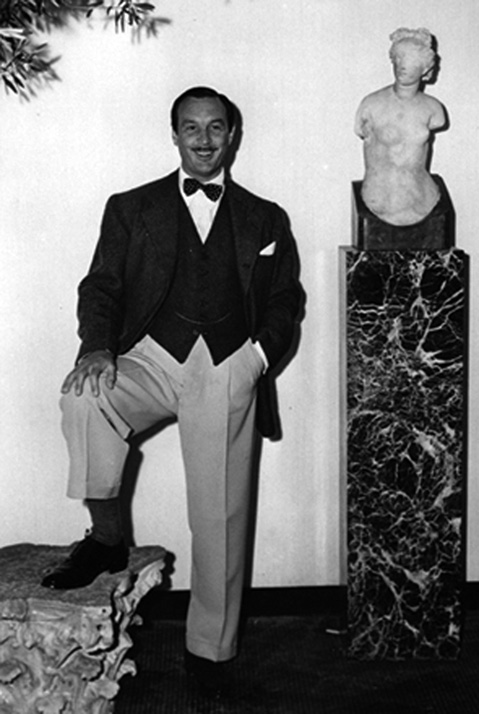

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art first opened its doors in June of 1941, and 70 years later the museum’s permanent collection is looking better than ever. What’s more, the museum’s ascendance is largely due to the taste and prescience of one individual—Wright S. Ludington, the man who not only collected the magnificent set of modern works on view in this new special exhibition but also is responsible for acquiring and donating the largest part of the museum’s holdings in Asian art and ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. Ludington, who lived from 1900 to 1992, was born in Pennsylvania and traveled extensively, but it was Santa Barbara that most fully captured his imagination and his heart.

Ludington’s chief strengths as a connoisseur were his powerful intellect and his unerring instinct for genuine innovation. Drawn to Modernism, which was curated by Rachel Sloan, brings together more than 40 works, many of which Ludington purchased right before the founding of the SBMA. In every piece on display, one sees the highest possible degree of aesthetic and cultural urgency. It may seem a stretch to compare the SBMA to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, but visiting and enjoying this show, and thinking back to what the world was like when the SBMA was founded it in 1941, it is fair to say that Ludington and his circle were mere steps behind Alfred Barr, Paul Sachs, and the Rockefellers in campaigning for, and thus creating, the enormous market for 20th-century modernism that exists today. In fact, Ludington’s version of the rise of abstract art may, in some ways, offer a more nuanced version of the story than the more familiar litany of New York-based triumphalism.

Ludington collected like a cultural critic, stating that “the whole point of collecting is not only one’s enjoyment, but the learning of what happened in the world creatively over the years: how one thing led to another.” He wanted to own and display not just beautiful objects, but works that demonstrated new ways of seeing that really mattered. This is what made Ludington an early fan and collector of Picasso, and it’s also what drew him to such other favorites as Oscar Kokoschka, Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse, and Auguste Rodin.

Perhaps the single most compelling stroke in this thought-provoking installation is the alignment of Rodin’s sculpture Head of Jean d’Aire (1886, cast in 1963) with the large photo panel depicting Ludington that guards the entrance. An integral part of the complex and multi-faceted Burghers of Calais project, the Rodin piece exemplifies the transition from 19th-century representational art to the abstraction characteristic of modernism in the early 20th century. Ludington saw more completely than most that representational art was bursting from within, yielding new forms that would have a profound impact on the art of the future. Plucking the Head of Jean d’Aire from out of the Burghers constitutes the collector’s equivalent to the Promethean theft of fire.

Elsewhere, his eye is similarly keen, as in the stunning series of works by British artists that Ludington assembled while serving in World War II. The final words on this superb exhibition should come from Henri Matisse, here represented by a pair of line-drawing portraits and a bright-colored cut-paper poster. In his magically spare and evocative drawings, Matisse claimed his object was to “put my emotion to line and [model] the light of my white paper.” In his role as collector, Ludington succeeded in doing something remarkably similar, by looking at the white paper of modern art and modeling its light into a collection that grows more interesting and more significant with every passing year.