Documentary Digs Into the F-Bomb

Interview with the Writer and Director of the Film That Dare Not Speak Its Own Name

[WARNING: PROFANITY AHEAD]

We’ve all heard it, and most of us say it, but there’s surprisingly little understanding out there on the history of the F-word and why it permeates almost all aspects of our lives.

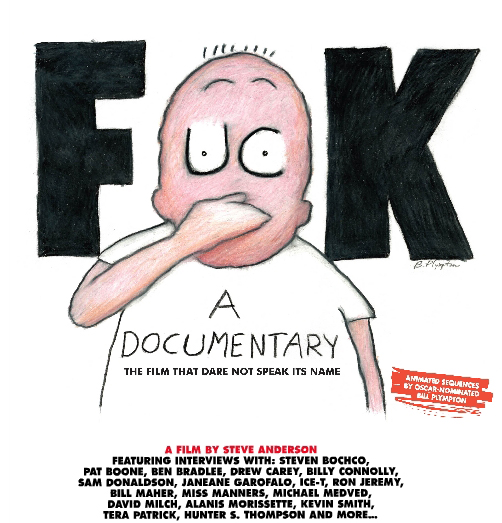

In his film, F**k: A Documentary, writer/director Steve Anderson checks out all sides of the prolific profanity through interviews and television and movie clips. The film makes its Documentary Channel premiere tonight, May 28, at 2 a.m.

In a recent interview, Anderson talks about his work and his newfound familiarity with the F-bomb.

What’s so great about “f**k?”

The most brilliant thing about the F-word is you can use it literally as every word in the sentence. You can say, “F**k, f**k you, you f**king f**ker!” and people know exactly what you’re talking about. There’s no disguising what it is. And there’s no other word like that in any language.

For most people, or a lot of people, it’s the word that you use around friends. It’s funny; you’re comfortable with the people you’re talking to. It’s just such a great word. It can express joy, it can express pain, it can express anger. Whatever sort of context you put it into, it makes that context even stronger.

But it’s interesting. Even people who are comfortable with “f**k” have to figure out what kind of social situation they’re in. Kevin, who’s in the film, says whenever he goes into a meeting he’ll never use the word first. But once someone else says it, all bets are off, and he can swear all he wants. If you’re talking to your mother, your grandmother, you’re in church; it’s certainly not appropriate there … If I did still go to church, I wouldn’t sit there in the pew saying, “f**k.”

Do you have a favorite usage?

For me, it’s kind of that standard they’re-all-my-children sort of thing. I go through stages … I don’t swear as much after the film as I did before it, but I admire the word even more.

There’s so many ways to use “f**k.” You can put it in the middle of words, like “un-f*king-believable,” and you can use it as a verb, a noun, an adjective. It’s a really interesting word, linguistically.

What’s the history of the film?

A number of years ago, I just sorta said it as a joke, “Hey, we should do a documentary about the word f**k.” The second I said it, I knew it was kind of a really brilliant idea. It hadn’t been done yet, and it’s a word right at the center of controversy — always has been, in so many ways. There are curse words that aren’t as bad as f**k and there are curse words that are worse than f**k. But it just seems to be this tipping point word. People are either comfortable using in most situations — not all situations — or they just recoil against it and think it’s the symbol of society going bad. I realized that we could both have fun with the film by looking at the history of the word and look at it in various social situations, like politics, and sports, and religion.

Where did “f**k” come from, then?

No one really knows where it came from … Most people think that “f**k” is an acronym — either “fornication under consent of the king” or “for unlawful carnal knowledge.” None of that’s true. People want “f**k” to have this sort of magical, mysterious meaning. But really it just sort of bubbled up from the muck years ago. We’ve interviewed some of the highest scholars from Oxford English Dictionary and they can pinpoint where “f**k” was first printed and different uses of it over time.

It was first printed in the late 1400s, but it had been around a long time before that. It always meant the sexual act, you know, it was more graphic. It wasn’t really until the First World War, and then really the Second World War, where it took on a broader cultural usage. Men in battle needed a word that could get your attention really fast. If you say, “Get out of my way,” that’s one thing. If you say, “Get out of my f**king way!” then all of a sudden it’s like, WOAH! It raises the level of discourse really quickly. Men in battle really needed that. It was both a useful word for them and a real outlet to let off steam. From there, it entered real lexicon.

I’ve been kind of thinking about “f**k” in a social context. Back in the Bush years, the FCC really clamped down on it. You know, like when Cheney told Senator Leahy to go f**k himself on the Senate floor. Now with the Obama administration, you don’t really hear much about it. Even Joe Biden whispers “f**k” to Obama in a press conference and everybody just kind of titters about it! So “f**k” kind of ebbs and flows with society.

How many “f**ks” are in the film?

I am kind of oddly proud that the film completely breaks any record of using the word. But the honest answer is it’s not really countable. We counted the times it either was uttered by somebody in the film or it was sung in a song — we use a lot of great music that uses “f**k.” And then [we counted] any time it was written on screens … on broadcast television, you could be fined for any one of those. Some of our background graphics — and I’d say there are probably 100 or so versions — are made up completely of hundreds of “f**k” words. You know, not just “f**k” but “motherf**ker” and stuff like that. The official count on Wikipedia is 857 … on the DVD there’s actually a special feature that’ll count along as you play the movie.

But I really don’t know. It was funny — we really tried. We all took turns watching the film, counting, because we wanted to know. And we all came up with different numbers. We actually did a kind of comical version of the film where we just took the “f**k” clips and cut them together into about a four-minute Youtube video.

Where do you go from “f**k”?

Drew Carey, at the end of the film, says, “When are you going to make the ‘c**t’ documentary? That’s the really bad word.” But I don’t know. It would be a very interesting film to make, but I don’t think I’ll be the one to do it. I’m fine with “f**k.” There was that book, “On Bulls**t.” “Bullshit.” It’s a great word … it means so much more than the word itself. Something can be bullshit; people can be giving you bullshit. And then there’s that film about the N-word, another powerful, totemic word in our language.

You know, I’m really proud of the f**k film. It’s a little dated because it came out at the end of the Bush admin [in 2005], and at the end of the film we open it up to talk not just about the word but to talk about free speech issues. And at the time we were talking about Janet Jackson’s nipple, and Howard Stern’s FCC fines, and others. It contains fleeting glimpses of certain things.

How did you pick interviewees? Who was the most interesting?

I wanted a variety of people from both sides of the spectrum, both conservative and liberal … not just the sort of standard people you might expect — people that people had heard of but hadn’t seen very often. Oddly enough, one of the first people to say yes was Pat Boone. I had done this program with Pat as a cameraman about eight years before, and I thought, what a great representation of that portion of society; somebody that’s really clean cut; wouldn’t dream of ever saying it. Once we got him and a couple other big names — Janeane Garofalo, Bill Maher — then it started to tumble forward. We got some interesting names. We also had the last filmed interview with Hunter S. Thompson before he died.

Tell me about the interview with Hunter S. Thompson.

It was an incredible experience. I dedicated the film to him, mostly because I really admire the guy and his work both as a writer and a journalist, and to celebrate the fact that we were able to interview and spend some time with him. We went up to his house in Colorado, and spent two nights up there. The first night we didn’t do any interviews, but the second night was, at least in my mind, a pretty epic night. We were up there about eight hours, so we got to hang out with him for that long. He’s a very funny guy.

He was a little moody when we got there. His wife welcomed us in. Hunter was getting ready, so we started setting up in this other room. I finally decided I needed to start to engage Hunter. It was the night that there had been a big basketball game, and there had been a big fight in the stands. It had been this big news. I knew he was a big sports fan, so I went in and started asking him about that, and suddenly he opened up. He had a few cocktails, and I brought him up a bottle of expensive whiskey.

The most interesting thing about Hunter is he would often go off topic. I’d ask him about the word “f**k” and its use in the language, and he’d start to answer, but then he’d veer off into some strange context of something else. But I could never stop him because it was all so interesting. He’s just such a raconteur, but he was just a little hard to understand … you really gotta focus in and kinda follow his brain pattern; what he’s saying; where he’s going. You wonder, is he going to come back around to a point or has he just gone off into the ozone or … ? I was just really intrigued watching him. It was maybe six weeks before he killed himself.

Was Hunter your favorite interview, then?

There were a lot of interviews that were fun — really all of them.The people on the liberal side — Drew Carey, Billy Connolly — are really hilarious. And we had porn stars in there. You know, there is no film ever produced that has both Ron Jeremy and Miss Manners. I love the sort of juxtaposition of all these people, and editing it was a lot of fun. I wanted to get a lot of people’s feelings and tell a story. The film really doesn’t go too deep into any certain segment. We look at “f**k” in politics, sports, religion, films, TV, radio. What really comes across is how widespread this word is. It’s used in every facet of society. The FCC can fine you for it, but if you’re on satellite radio, you pay $10 a month and you can hear it all you want.

I wanted some musicians to talk about how “f**k” works in music. We have Ice-T talking about it in rap; Chuck D is in the film — he did “F**k the Police.” So is Alanis Morissette. I love her liberal use of the language. She had been involved in some censorship in Canada, so she works perfectly for the more popular music game.

Did you ruin the world for anybody?

One teacher in Philadelphia showed the film to his grade school class and got fired. I got on the phone with him — obviously, I wanted to talk to him — when we did a live radio show. He had a good explanation: the kids in his 6th grade class were using “f**k” all the time; he couldn’t stop them. He had heard about this film, looked at the history of it … he wanted to show it to the kids and get them some context of this word that they use so often, and said he’d been trying to get them not to use it so much.

What got him fired was not showing the film but just one short clip of a couple in Europe. It’s in the segment where we’re talking about Janet Jackson’s nipple. It’s exposed for half a second … it’s really her nipple ring, and it causes this grand debate in American society, goes to Congress, gets FCC fines. Six months later, to prove a point, this couple that runs a Web site called “F**k for Forests” goes on at this concert in front of a few thousand people, the band is playing, they whip off their clothes, and they start doing it on stage. And nothing happens to them. The point we’re trying to make in the film is the differences between European society and American society. That scene is what got the teacher fired — not the “f**k” word.

In a couple of early cuts of the film I actually had a few porn clips in there; I thought it was important, if we’re going to be talking about the word “f**k,” to show people f**king. But at some early screenings, liberals reacted against it. They were like, “Oh my god, don’t show me that! I can handle the word, but don’t show me porn!” It was funny: they had the same gut reaction to pornography that most conservatives have to the word. Finally one woman said she’d love to show the film to her father. She said, “He’d love to hear about the word; the language.” But she could never share it with him with [porn] in there. Finally I had to listen to the audience … I’m not sure it would have been able to be shown theatrically … So I took the graphic pornographic shots out. There’s still a few references to it, and we do some great animation about Bill Clinton where you see some people in animated form doing it, but there’s no raw pornography in there.

How has the film been received so far?

We were very successful in film festivals. We played it probably in over 100 worldwide. Film festivals loved it because of the title. They’re always a little more risk-taking; they can put “f**k” right in their program, and say, “Two tickets to f**k!” They love having that sort of dangerous aspect. And then TH!NKFilm picked it up, and it played in 60 to 70 cities across the country, theatrically. I’m really supportive of the Documentary Channel playing it. But it’s pretty funny: Even though they’re promoting it rather heavily, they’re premiering it at 2 a.m. — it’s not their prime time documentary. But I’m thrilled.

Does your film have a message?

I think the film is just a really entertaining and enlightening look at a really interesting word. And when we really get down to it, it’s a word! It’s four letters, and they have to be in the right order. People get a little giggly about it, but “f**k” is F-U-C-K– we all use it. We all talk about it. It’s one of the best words ever.

I think people get a kick out of watching the film. In the theater, people really laugh out loud. At film festivals, we often held Q&As after, and people could not stop inserting “f**k” into their questions. People would be like, “How much was your f**king budget?” “How the f**k did you get this idea?” The movie gives people an opportunity to let their guard down, look at a word that we all use, and come to their own conclusion how they feel about it. Liberals are a bit funnier than conservatives, for some reason, so the liberals get the good laughs. But you do see both sides.