Google Mastermind Turns to the Stars

Wayne Rosing on Revolutionizing Astronomy from Goleta

In the heart of Goleta sits a nondescript gray building that houses dozens of world-class astronomers, engineers, and machinists toiling away to create the first global collection of large-scale telescopes connected to and managed by a central location. When it’s finished — the goal is by 2013 — the group of one-meter telescopes, accompanied by a smattering of smaller units, will dwarf any land-based network of observatories on the planet. It’ll be able to see anything in space at any time, without any blind spots or downtime.

Heading the symphony of creative brainpower and innovative technology that is the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope (LCOGT) Network is Wayne Rosing, a central figure in the computer’s evolution from novelty to necessity and a lifelong admirer of things that go boom in the night sky. A computer guru who’s worked for Apple, Sun Microsystems, and Google — where he ran their engineering and technical programs for five years — Rosing sat down with The Independent at his headquarters to talk about the gobs of astronomical data he gets giddy sifting through, and how anyone with an Internet connection will be able to view firsthand what LCOGT’s observatories see thousands of light years away.

What similarities do you see between your time at Google and LCOGT? As I did at Google, I work with very creative people given challenging assignments and pushed to the max intellectually to do something that’s never been done before. We’re trying to do things that aren’t orthodox but address known problems. I felt like [the lack of a world telescope network] was the next problem.

So what sparked this idea? The original idea of establishing a network of telescopes around the world was articulated in the early 1980s by more than one person, but I really latched onto it as something I was interested in doing because I was a very serious amateur astronomer. This has been a 30-year-long interest for me.

When did it all start coming together? I became fired up about this project in 2005. I decided I wanted to dedicate a large fraction of my time to it. Of course, this was after checking with my wife. She started a foundation that’s doing women’s health and empowerment work in South America, so we each have very major projects we’re doing.

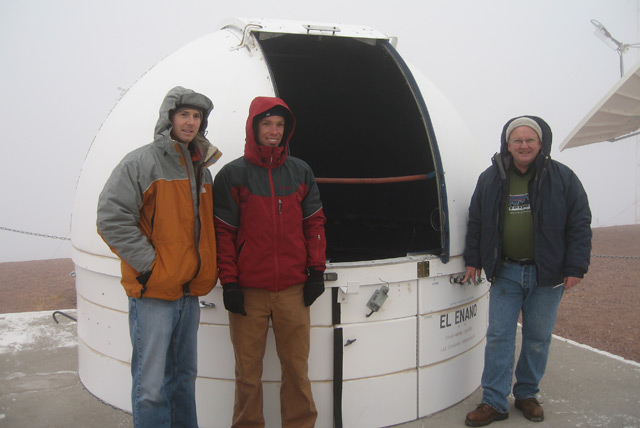

At the moment [LCOGT] is using two telescopes we acquired: one in Australia and one in Maui. Our first major installation is taking place right now in Chile. We’ll then add a location in South Africa, then Australia, then the Canary Islands, somewhere in west Texas, and somewhere in China.

What kind of reception have you received from host countries? We’ve generally received very cordial reception everywhere because the host institution gets a fraction of the telescope time as part of the rent. What we’re offering, too, is that equivalent fraction somewhere else in the world. They have access to the whole network.

As I know it’s a big focus of your vision, tell me about the educational elements of the network. The program will be mainly discovery-based. For instance, an individual may find out about us, then go to our Web site and think, “Gee, I’d like to try this.” They can then create an account and try some trial observations. It’s all free, and people will use the same system scientists use, entering the same kinds of requests, getting the same kinds of data back.

The assumption is teachers will start by doing that themselves, and then if they want to form an account, we have special ways to transmit the observations to classrooms. Kids will be able to see what a telescope sees. We have four people around the world who focus on supporting our education program.

Our primary education objective is not to teach astronomy. It’s to have a place where people can learn how science is done and how they can learn to think critically. What does it mean to do science? What does it mean to acquire data and draw conclusions from data?

Unfortunately, I think we live in a world where a lot of decisions are faith-based. Not in a religious sense, but what you think you heard on CNN or what you think you heard some congressman said, and it’s all about sound bytes. It’s not about deep understanding. It needs to be about critical thinking.

How much does each installation cost to build? Facilities cost well over $6 million apiece. We have a foundation to fund them, and we get a small amount of grant money.

All of the facilities we’re building are identical, which will make them much easier to maintain.

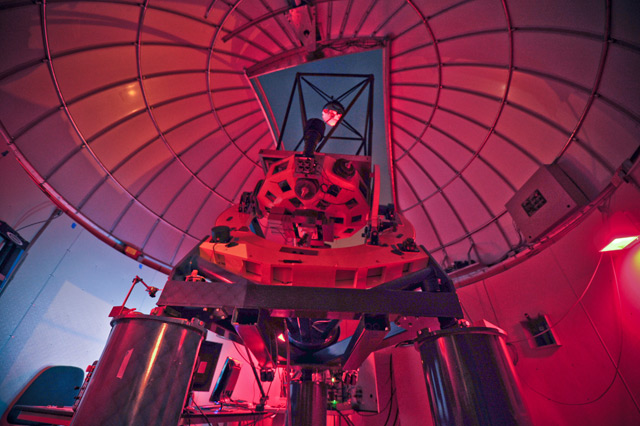

A finished one-meter telescope will weigh 2-2.5 tons, but they’re built with lightweight assemblies that can move fast. Traditional telescopes are very big, massive things that move very slow. We don’t want to waste time. We want to move to the next object, so our telescopes can move 10 degrees a second. And multiple telescopes can be pointed at the same event, or each at different events.

Each one-meter unit takes around two months to manufacture, with five to six people working on it. We have to make everything we need. We can’t buy anything. There’s been no collaboration with NASA or anyone else, but we’ve learned from other projects’ successes and failures.

Do you have the desire to get something into space? No. A space project would cost more than our whole project. It would cost a few hundred million dollars for even a small [observation] instrument.

Why did you choose Goleta as your home base? Mainly because of the area’s affinity to UCSB. There are a lot of great post-docs there. Carpinteria was the other choice, but it was inefficient in terms of UCSB students working with us. I’ve also lived in Montecito since 2000.

Who composes your team here? We have about 50 people. During the summer, we have a lot of interns who come from Dos Pueblos High School Engineering Academy, UCSB, and Cal Poly.

The first year, we went looking for post-docs because no one knew who we were. In the second and third years, we had to do much less searching; LCOGT has gotten a name for itself. We’ve published approximately 400 papers in the last five years, and the group collectively has been associated with the discovery of almost 40 extrasolar planets. Until the data started coming out of the NASA satellite program, ground-based discoveries were around 400.

At this point in the interview, one of Rosing’s employees poked his head into the room and inquired about happy hour. Asked to explain, Rosing said everyone in the office “tends to have a bit of a drink down at the Mercury Lounge on Friday nights.” He also mentioned that any time there’s a three-day weekend, he closes the office on the accompanying Friday or Monday to give everyone four full days of rest. “There are advantages to being the boss,” Rosing said with a wink.

What are you primarily looking for? We’re interested in things that explode — stellar explosions, mergers, black holes, neutron stars, and so on. Transient phenomena — they tend not to happen again. What’s unique about our observatory on the ground is we can observe for long periods of time. We’ve also dedicated our observatory to the principle that we’re going to be available with robotics to go to the important scientific events if we get a trigger from a satellite or we see something on the net about some new phenomenon. We’re prepared to go there to follow up, and we can do that uniquely because we’ve got telescopes that cover the whole sky.

Other than NASA, we’re the only people who can do this. Weather will occasionally spoil that statement, but with the diversity of sites, it won’t be nearly as chaotic as a single observatory.

Who mans these telescopes around the world? At each of the large telescopes, we have a single employee who is the observatory manager. At the bulk of the rest of the sites, we will not have an employee. The big telescopes are completely robotic — they are not attended at night. They’re operated essentially from here, but it’s all done with programming. There’s no one up all night watching the telescopes. All the data flows here, and the analysis is done by our science team.

Do you like observing one thing more than another? I would say, for me, it’s less the object and more of the difficulty of the observation. The more challenging it is, the more interesting it is for me. I recently observed a small planet-like object near Pluto. We had a week’s notice, and I built a complete instrument to do it. I went to [the Maui observatory] with it in my briefcase, attached it to the telescope the night before, then got the observation. That was personally very gratifying.

In the long run, the areas where I’ll be very focused will be the scientific computing, the application of very large-scale computer resources to a very small scientific team. We will have enormous data. Basically, upwards of 84,000 observing hours in a year’s worth of data. Most observers, in typical observing mode, might get 10 to 12 nights a year. So we’re talking about thousands of times more data than the average academic astronomer is used to. Everything we do has to be done on a completely different scale.

Track LCOGT’s progress and take a peek at what celestial events and bodies it’s discovered or is currently tracking at lcogt.net.