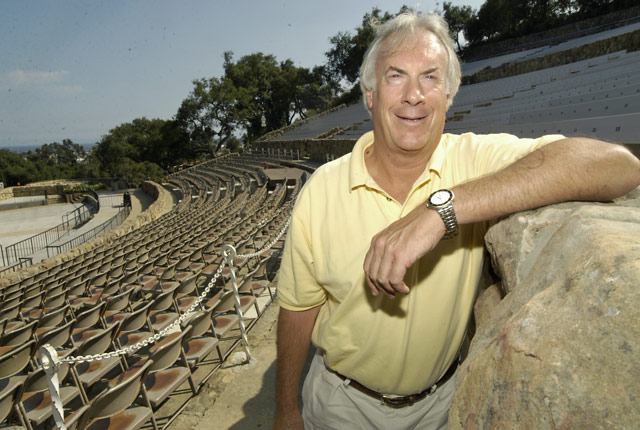

Sam Scranton’s Legacy at the Bowl

Former Exec Director Goes Behind the Music

People who know him know that Sam Scranton loves to talk. Even more, he loves to talk about the Santa Barbara Bowl, where he has been a backstage force to be reckoned with for more than three decades, serving as executive director since 1994. So it surprised many when he suddenly—and even odder, quietly—retired last year. “It was time; I was almost 60, and I had left surfing and playing music behind for a long time.” He was tired, he said, and dreaming about escape from the Sisyphean labors of the Bowl—decibel curfews, neighbor relations, tetchy artists—a year before he left an almost un-vocalized legacy behind.

Scranton came on board in the 1980s, when Old Spanish Days (OSD) decided to let an outsider—Ray Klein, of Enterprise Fish Company—run the Bowl operations. Even that early, Scranton was hanging out with Patrick Davis, the not-yet county arts commissioner, talking about forming a nonprofit. “We were already convinced it would be the only way to raise money to pay for upkeep and improvements,” said Scranton. Attempts to discuss Bowl preservation with county politicos were then met with guffaws and sometimes even rough prejudicial language about the venue’s clientele. Though the nonprofit was mostly a dream back then, Scranton gathered big-deal musician friends like Joe Walsh to build the now-legendary annual New Year’s show near the Biltmore. Fundraising for the then-imaginary foundation had already begun.

In the 1990s, Scranton really came into his own, first watching the Bowl move from OSD to county control, and then, months later, to the Santa Barbara Bowl Foundation. From there, Scranton, with friends like the late, great Rex Marchbanks, and later Moss Jacobs, a club promoter in the area who cut his big concert teeth in Los Angeles, took over. At the same time, a board assembled, raised money, and began making improvements, all of which were substantially applauded and, more surprisingly, completed on time. Initial cost estimates doubled, but they raised it all in loans and grants and paid their bills. The Bowl, meanwhile, ran at a profit.

It all paid off handsomely in the aughts: big shows, ample bathrooms, and improvements that managed to draw in the well-heeled without much offending the regulars of yore.

If you ask the vociferous Scranton of which aspect he is proud, he shoots right back, “All of that. What am I proud of? There are people who said ‘You’ll never do it.’ And we did it.” Scranton admits that his life at the Bowl wasn’t always harmonious, but it was productive. “Musicians right away came to us and said, ‘We can put more stuff up there than we could at the Hollywood Bowl.’ We made the Bowl too cool not to play.”