Where Do All the Bobcats Go?

UCSB Grad Student Serra Hoagland Maps Goleta’s Wildlife Corridors

Amid the buzz of afternoon traffic on Hollister Avenue, Serra Hoagland gingerly walks off the sidewalk and down the side of a jungled creek bank, carefully moving branches to avoid hitting hairy spiders or ripping their webs. After reaching a dry creek bed, the recently graduated UCSB master’s student steps toward a graffiti-covered bridge under Hollister, where she points out sandy ground pockmarked with animal prints and the wide, high passage through to the airport-surrounding wetlands beyond.

“This one is really good,” says Hoagland, who spent most of 2011 investigating wildlife corridors such as this throughout the Goleta Valley, a place where suburbia is surrounded by an impressive patchwork of open space. “This is awesome.”

The same can be said for Hoagland’s recently completed project, which rides a growing wave of wildlife movement studies being done across the globe, all spurred by the realization that broken-up habitats spell doom for certain species. From the Himalayas to the Netherlands to Central America, government agencies are protecting existing corridors and even establishing specially designed crossings over highways and other manmade impediments where needed. “There is an increasing emphasis worldwide in mapping out these linkages, communicating their importance to decision-makers, and planning around them,” said John Gallo, currently a senior landscape ecologist with The Wilderness Society, but formerly the director of the Conception Coast Project, which works to protect nature along the Gaviota Coast and elsewhere. “Serra’s work is a great example of blending theory and on-the-ground observation to tackle this challenge.”

Although smaller in scale than, say, the China-Russia Tiger Corridor, Hoagland’s work — which was funded by the Coastal Fund at UCSB and the Santa Barbara Foundation — is already having an impact, at least in the City of Goleta. “The second we got it, I forwarded it to everybody,” said Anne Wells, a city planning manager, who explained that Hoagland’s study is a new reference tool for enforcing the city’s General Plan, which aims to protect all kinds of habitats, from sleeping spots to feeding zones, whenever new developments are proposed. “For most species to sustain their populations, they need all of those components,” said Wells. “Where they roost versus where they forage versus where they nest are frequently different places. In order to protect those species, you need to protect the corridor so that they are able to access the different pieces.”

Dimensions and Dead Skunks

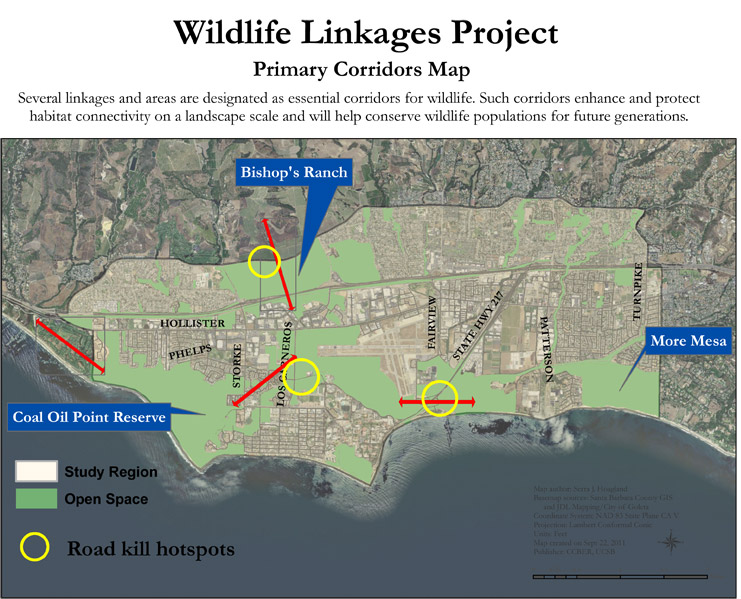

Starting in January 2011, Hoagland — a native of Placerville, California, whose Bren School–issued master’s degree was actually in oak woodland ecology but who did this study as a side project — identified 55 of these linkages spread across roughly 10,000 acres of land, from Cathedral Oaks Road down to the coastline between More Mesa and the Ellwood bluffs. In addition to those two large undeveloped properties, the study area included such de facto preserves as Bishop Ranch and the Goleta Slough around the Santa Barbara Airport, making the study about one-third open space. The whole zone is directly connected to the Los Padres National Forest in the mountains above, where countless beasts roam freely.

“It’s really good habitat for these animals,” said Hoagland, who revealed her project to the general public during the City of Goleta’s Bishop Ranch hearings in September, “and it’s interesting because it’s all fragmented.” In other words, the Goleta Valley is a dreamscape for scientists interested in the study of wildlife corridors.

Hoagland and a team of UCSB student interns visited each of the corridors; identified the type of crossing (culvert, bridge, etc.); measured its dimensions; described the surrounding habitat; noted lighting, water levels, and other human activity (homeless camps, taggers, etc.); and checked for evidence of animal use. Then she also compiled all available data on roadkill in the Goleta Valley, from the small (rodents, reptiles, etc.) to the medium (skunks, racoons, etc.) to the large (coyotes, bobcats, etc.), including some more surprising finds, such as four dead badgers and one run-over ringtail cat (which is actually related to the raccoon). By cross-referencing all that data, Hoagland identified a number of primary linkages, listed roadkill hotspots (watch out on Cathedral Oaks between Glen Annie and Los Carneros!), suggested places that could stand some improvement (such as Highway 217 near UCSB, and from Bishop Ranch to Hollister), and discovered that while 98 percent of the 55 studied corridors are suitable for amphibians, only 25 percent work for large mammals, which tend to be afraid of entering small spaces.

“It gives you a better distribution by species, a better look at small mammals versus larger mammals,” said Wells, the Goleta planner who also praised Hoagland’s study for becoming a new central hub for tracking regional roadkill data. “It’s also pretty interesting to see how far animals move. You think they’re very localized, but they’re not.”

Wildlife for All

But it’s not just fun for planners and scientists — Hoagland’s work is also important for the many residents who enjoy a walk through More Mesa or jog along the Ellwood bluffs hoping for the chance to spot a bobcat or badger. Without these mostly hidden passageways, such awe-inspiring experiences would become a thing of the past.

“The value of these open space areas is not only for people to run and walk through but also as exciting places to view and experience wildlife,” said Lisa Stratton, of UCSB’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration (CCBER), which supported Hoagland’s work. She is seeking grant money to build on it and hopes to collaborate with the City of Goleta, County of Santa Barbara, and Caltrans to reduce roadkills and improve the corridors. “By focusing on preserving and enhancing the connections between these significantly sized open-space areas and the mountains, we can help keep the food web functioning so that there are voles for kites to hunt, squirrels for hawks, and possibly coyotes to hunt ubiquitous skunks, gophers, and squirrels.”

Hoagland, of course, agrees. “When people hear that there’s been a bear down by UCSB, they’re like, ‘You’re kidding me! How does that work?’” laughed Hoagland, who will be pursuing her PhD at Northern Arizona University starting this fall but continues to work on this project. “People value having those types of animals in these areas, but you’re only going to get them there if you allow this type of movement.”

See more pics and get deeper into the project by clicking here and, to follow the work on Facebook, click here.