Newt Nixon

Gingrich Channels Tricky Dick in Campaign Appeals to Resentment

National Review, the house organ of American conservative thought, has provided its readers an intriguing insight to explain the brawl between Newt Gingrich and Mitt Romney over the Republican presidential nomination.

Dismissing conventional wisdom that portrays the increasingly entertaining Mitt vs. Newt spectacle in standard political language — moderate vs. right-winger, pragmatist vs. ideologue, establishment vs. Tea Party — essayist Kevin Williamson analyzed the conflict in far more basic terms:

“It is between those Republicans who disagree with Barack Obama, believing his policies to be mistaken,” he writes, “and those who hate Barack Obama, believing him to be wicked.”

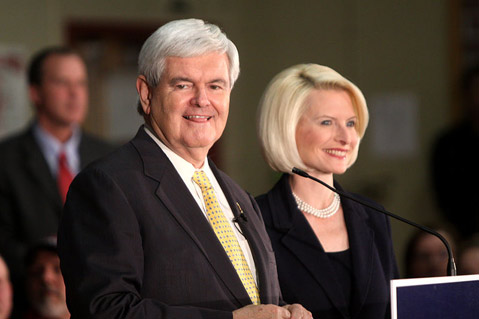

As the candidates campaigned in Florida this week, it was on political terrain reshaped by former House speaker Gingrich, who had suddenly and surprisingly disrupted the coronation march of Romney, trouncing the erstwhile front-runner in the South Carolina primary by tapping and channeling deep anger about President Obama among the GOP grassroots right wing.

Gingrich loves to compare himself to conservative icon Ronald Reagan, whose political brand was defined by optimism and sunniness; the Gingrich campaign, however, has been driven in recent days far more by the politics of resentment, recalling in its appeal, style, and language a darker and more brooding Republican president, the late Richard Nixon.

“Elections were won by focusing people’s resentments,” historian Rick Perlstein has written in his seminal political biography Nixonland, which argues that it was the 37th president, particularly with his 1968 campaign, who set down the red state / blue state template that defines American politics to this day.

“What Richard Nixon left behind was the very terms of our national self-image — a notion that there are two kinds of American,” he writes.

“On the one side, that ‘silent majority’ … who call themselves, now, ‘values voters,’ ‘people of faith,’ ‘patriots,’ or even, simply, ‘Republicans’ — and who feel themselves condescended to by snobby, opinion-making elites, and who rage about un-Americans, anti-Christians, amoralists, aliens.

“On the other side are the ‘liberals,’ the ‘cosmopolitans,’ the ‘intellectuals,’ the ‘professionals’ — ‘Democrats’ — who say they see shouting in opposition to injustice as a higher form of patriotism.”

As a matter of historical trivia, it’s worth noting that in winning the 1968 GOP nomination, Nixon overcame onetime front-runner and Michigan governor George Romney. The father of former Massachusetts governor Mitt, George, like his son, was a smooth-talking, well-coiffed moderate whose claim to fame was winning election as chief executive of a Democratic state.

As a political matter, however, the parallels between Nixon and Gingrich are more substantive, and focused on three streams of conservative resentment:

• Media: Nixon brilliantly used the “liberal media” as a political foil, casting major news organizations as tools of left-wing Democrats; Gingrich built his breakthrough South Carolina win on two bombastic debate performances in which he tongue-lashed talking heads Juan Williams and John King as “elites,” winning standing ovations, along with widespread voter support, for his attacks.

• Race: Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” which exploited the anger and resentment of whites about federal civil-rights legislation, made him the first Republican to dominate presidential voting in the South after the Civil War; Gingrich’s statements in South Carolina featured thinly veiled, dog-whistle appeals on race, as when he trashed Obama as the “food-stamp president” or thundered that Williams, an African American, was unfamiliar with “the concept of work.”

• Culture: Nixon defined as anti-American “bums” Vietnam and civil-rights protesters, contrasting them with “ordinary Americans” yearning for “law and order.” Gingrich cast Obama not as a partisan rival with whom he disagrees but as an existential threat to America, a dangerous “left-wing radical” who appeases Islamic terrorists and empowers “grotesquely dictatorial” judges; his pitch was widely applauded by right-wing Republicans who say they want to “take back our country” from the foreign Obama, whom they have viewed from the start as an illegitimate leader.

It is unclear whether Gingrich in the long run can overcome Romney’s huge advantage in money and organization. What is clear, however, is that in Romney he has a central-casting foe — rich, privileged, and backed by the GOP establishment — against whom he can position himself as a self-styled populist alternative.

“It’s not that I am a good debater,” he said on election night in South Carolina. “It is that I articulate the deepest-felt values of the American people.”