NAMM Time, Plus Upcoming Jazz

Regina Carter, Yellowjackets, and More

SURVIVING NAMM: After twenty-plus years (best to lose count at some point) of going religiously to the NAMM show, the question of why becomes moot. It’s a happy habit, and a joy and a drag on multiple levels. For this music journalist, musician, closet gear geek and fetishist, the prospect of going back to the circus/expo/showroom/gear hypefest each January in the sprawling outpost of the Anaheim Convention Center has become an annual pilgrimage, like it, love it, and/or not.

Things change and stay the same at NAMM, year after year and decade after decade. The meat ‘n’ potatoes stuff of guitars ’n’ drums (’n’ pianos and tubas, et al) have yielded showroom space to the advance of digital technology, and this year, in particular, the place might be subtitled iNAMM. Apps and software for iPads and iPods ran the gamut, from easy-use teleprompters (such as the one Steve Martin used when he played the Granada), electric guitar multi-effects command posts, recording software and other ideas bursting forth in this new i-arena.

Live musician sightings are critical real time buzz moments at NAMM, which seem like a business-first enterprise at times, mixed in with the unspoken but clearly felt “religious fervor” of musicians gathering in a musical place.

On the Thursday when I made my whirlwind tour through NAMM ’12, guitarist Wayne Johnson and his trio were kinder, gentler fusion in the always cozy Taylor compound, and jazz organ great Dr. Lonnie Smith was burning in the Hammond booth, within earshot, ironically, of the digital zone and the likes of the AVID Pro Tools temple. Downstairs, blues-rock guitar master Kenny Wayne Shepherd was awkwardly posing and naturally riffing in a small booth, keeping his volume to a minimum, less the volume-meter-bearing “Sound Control” peacekeepers would register dismay and give orders to diminish the Ives-ian clamor.

Of course, NAMM’s Ives-ian clamor is part of the charm and proof of the timeless vitality of the music biz. Religion meets capitalism meets scantily clad women and scowling rockers and dweebish engineers, all under the bodacious, multi-farious big top.

JAZZ NOTES FROM NEARBY: Suddenly, this winter, the jazz-hungry among us in this jazz-challenged town are getting a bit of satisfaction in the next couple of weeks. On Friday, February 24, the Jazz at the Lobero series continues with the arrival of command jazz violinist Regina Carter, bringing her African-themed “Reverse Thread” project to the room.

At the Lobero this Friday, things kick into swing, and fusion-flavored grooving, when the Yellowjackets pay a rare visit to town in a rematch with mighty fine and tasty guitarist Robben Ford. It was Ford who essentially, and half-accidentally, launched the Yellowjackets, when he hired founders Jimmy Haslip, bass, and Russell Ferrante, keyboards to play in his band for Ford’s late ’70s album The Inside Story. Ford moved on, but the “backup group” began in earnest, and has built up a solid artistic life for 30 years and counting. Neither a straight-ahead jazz band or a panderer in the dreaded “smooth jazz” game, the Yellowjackets have charted a respectable post-fusion, Weather Report-influenced course, especially since inducting masterful tenor saxist Bob Mintzer into the fold.

Friday’s show is doubly significant in that this is a high profile edition of the annual TRAPS (The Rhythmic Arts Project) benefit, supporting Carpinteria-based drummer Eddie Tuduri’s inspirational organization, dedicated to educating those with disabilities through the universal power of percussion and rhythm.

Meanwhile, the cool and humble Danish outpost of Solvang continues its effort to make the town—and those of us within driving distance—safe for jazz. This is the town which hosted a brave, if short-lived Solvang Jazz Festival for three years, through the organizational efforts of Crusaders drummer Stix Hooper.

As of Saturday, Solvang again increases the jazz peace with the launching of the “Famous Jazz Artist” series at Terrace Dinner Theater (upstairs at Manny’s Restaurant, 1693 Mission Rd.), an expansion of the long-standing series in Cambria run by vibist Charlie Shoemake and his wife, vocalist Sandi. As a special guest in this first of hopefully many a dinner-show series ($35 wins you dinner, starting at 6, and two sets of jazz by some of SoCal’s finest), the respected L.A. alto saxist Lanny Morgan will head up the coast. The fine bebop-fueled Morgan is one of those top drawer jazz players who for many years made a living in studios (recording, television and film soundstages) by day and heeded the jazz muse by night, playing in Supersax for almost twenty years. For info: 691-9137.

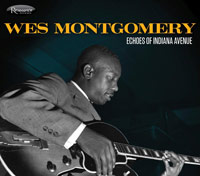

FRINGE PRODUCT: Wes Montgomery, Echoes of Indiana Avenue (Resonance).

Even as the years go by and jazz guitar becomes settled in its ways, and the population of dazzlingly proficient and well-studied, riff-accessing guitarists expands from the younger generation upward, the fact seems all the more clear: Wes Montgomery was a musical miracle of jazz guitar. A humble, self-taught and late-blooming player, Montgomery is an example of the natural jazz wonder, who played—with his thumb, rather than a pick—rings around other guitarists before or since, but always with a bone-deep sense of musicality.

And the story deepens a bit with the recent release of Echoes of Indiana Avenue (Resonance), an impressive set of digitally cleaned-up live tapes from his days as a passionate “unknown” player in his hometown of Indianapolis. As history tells us, Orrin Keepnews “discovered” Montgomery and cut several classic albums for the Riverside label, a discovery heard around the world. But the tracks heard here, facilitated into album form by famed scholar Michael Cuscuna, provide some fascinating, and musically bold pre-history to the tale of Wes. Details are sketchy about the locations and dates, but the spirit is vibrant and juicy.

The guitarist, sounding in fine form in unnamed joints where the ambient nightclub noise adds a layer of mystique, is joined on these tracks by various musicians, including his brothers, Buddy on piano and Monk on bass, who would become his bandmates as Wes’ star rose, and pianist-organist Melvin Rhyne. Hearing Wes summoning up heat and inventive lines on the standard themes of “Darn that Dream,” “Body and Soul” and “Nica’s Dream”—and he even plays “Misty” for us—gives a retrospective you-are-there perspective on a friendly musical genius in his hometown, before-the-fame-game comfort zone. The nine-track album takes a slight left turn, as Wes’ tone gets gruffer and bluesier, for “After Hours Blues,” replete with peanut gallery comments by lucky patrons in the club that night, little knowing that their words would be in some small way immortalized, or that this “local hero” guitarist would, ten years later, have cemented his place at the top of the pantheon of jazz guitar. Or that he would die far too young, of a heart attack in 1968. For current and future Wes fans, file this one high on the listen-up index.

Fringe Beat has gone cyber, facebooked and twittered (@FringeBeat), and myspaced and ?. Please join, if inclined.